Book Review: “House of Names” — Back to the Greeks

Colm Tóibín travels back to ancient Greece in House of Names, a vibrant, neatly balanced retelling of the tragedy of the House of Atreus.

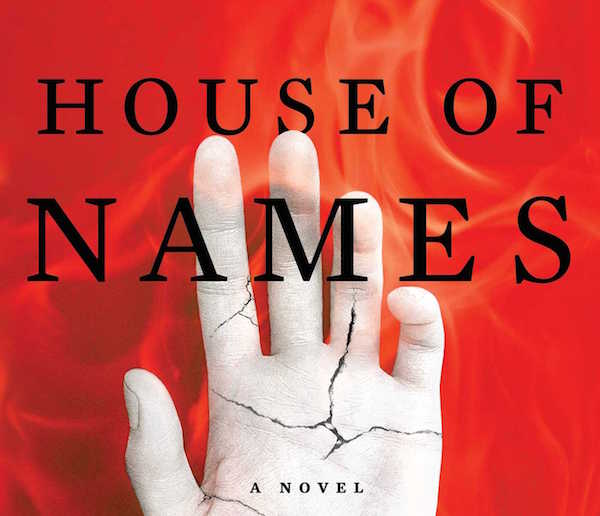

House of Names by Colm Tóibín. Simon and Schuster, 288 pages, $26.

By Lucas Spiro

I saw Colm Tóibín read and speak at Cambridge’s Brattle Theater the other day, promoting his latest novel House of Names. When asked about the genesis of the narrative, the author said he didn’t want to write another ‘Irish’ book — he was sick of umbrellas. Instead, Tóibín travels back to ancient Greece in House of Names, a vibrant, neatly balanced retelling of the tragedy of the House of Atreus.

Of course it must be noted that, at least thematically, this is familiar territory for him and many other ‘Irish’ volumes. It’s a drama about a dysfunctional family whose members fester with secrets and an obsessive preoccupation with violence and revenge. Religious prescriptions are challenged by some but strictly adhered to by others. Tóibín’s approach is to fill in the gaps left by the ancient Greek tragedians; he humanizes and contemporizes the larger philosophical concerns of his source material, swapping buckets of rain for meditative buckets of blood.

The novel is told from four perspectives — Clytemnestra, Orestes, Electra, and Clytemnestra’s ghost. The narrative begins with the sacrifice of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra’s eldest daughter, Iphigenia. Agamemnon is desperate for his fleet to sail for Troy, but there are no winds to carry his army across the sea. He invites his family to join him at Aulis. Clytemnestra believes that Iphigenia is to be married to Achilles — she is shocked to discover that Agamemnon plans to sacrifice his own daughter to the gods in exchange for a favorable wind. Once Agamemnon realizes that his wife has found out his true purpose, Tóibín gives us a tender scene of a family about to unravel, a moment pregnant with a sense of loss. Clytemnestra and Iphigenia walk in on Agamemnon when he is play sword fighting with his son Orestes: “The longer this jousting went on, the more I realized that he was afraid of us, or afraid of what he would have to say to us when it stopped… I smiled because I knew that this would be the last episode of happiness I would know in my life.”

After the brutal murder of Iphigenia, Clytemnestra begins to plot her revenge. She not only turns her rage against her husband, but against the gods, who she realizes are utterly indifferent to humans. She innocently believed that the marriage to Achilles would alter her family’s fate, that it would “end what began before I was born, before my husband was born. Some venom in our blood, in all our blood. Old crimes and desires for vengeance.” Instead, she accepts that fate is not the responsibility of the gods, but the result of something more material, something human. In this sense, Tóibín follows in the footsteps of Jean-Paul Sartre and his Nazi-era drama The Flies, looking at Greek tragedy through the lens of existentialism and its assertion of the unbearable burden of freedom. From this perspective, the story deals with the demands of human responsibility, the agonies of grappling with circumstance and reaction, cycles of violence and desire. Clytemnestra recruits and takes Aegisthus as her lover. He is cunning and manipulative, an old pro at placating his desires, his ravenous and indiscriminate sexual appetite as well as a lust for political power. When Agamemnon returns from combat, victorious and enriched, Clytemnestra takes her revenge, slicing his throat and leaving his dead body on display in the palace for everyone to see.

Author Colm Tóibín — his latest novel is resolutely contemplative and demands patience.

Orestes, still a boy when his father is murdered, is kidnapped during this period of chaos along with the children of other powerful people. He escapes with two of his friends and then chooses to take a long journey back to the palace. Orestes’ development is stunted by a frustrating naïveté. He is more puppet than person, a pawn in the machinations designed for him by his friend Leander and his sister Electra. Orestes will be a familiar character to those who have read Tóibín’s coming-of-age novel Brooklyn, where the indecisive Eilis causes harm to others through her lack of understanding and inaction. Orestes eventually commits matricide, which is necessary to everyone else’s plans (though something they are unwilling to do). But his passivity makes him both pitiable and, because he is so easily manipulated, a somewhat horrifying figure.

Electra has a smaller role, although she eventually manages to have Orestes kill their mother. Unlike her mother, she responds to her family’s trauma through silence and devotion to the gods. She remains either hidden away in her room, “an outpost of the underworld,” or moves in and out of the shadows, acting as our eyes and ears to the palace intrigue and paranoia, which are ripping the family as well as the kingdom apart. But, as her own sense of self-importance grows, she begins to turn into her mother. Orestes observes at one point that even her “voice, like her mother’s, had a way of emphasizing that she controlled things.” She abandons piety and embraces revenge once she becomes occupied with running the government. Orestes, too, becomes like his father — weak and easily driven by circumstances.

Some critics have described House of Names as a thrilling and adventurous page-turner. But that kind of gush is misleading; the novel is resolutely contemplative and demands patience. For all of the plot’s bloodshed and action, Tóibín’s language is remarkably restrained. Perhaps he senses that the over-the-top reactions in the ancient tragedies might seem a little ridiculous to contemporary audiences. In the hands of a lesser novelist, House of Names could well have deteriorated into a gratuitously savage soap-opera. But Tóibín’s refined, almost staid prose generates a graceful distance between what is happening on the page and its impact on the reader. His reticence has a timeless quality, giving the book a sense of harmony despite the roiling of the dramatic material.

But this stoicism also distorts the seething passions, the hysterical oomph, of the confrontations and revenge sequences, particularly during Orestes’s return. There is a certain defensive flatness here, especially in some of the dialogue exchanges, as if Tóibín was (too) afraid of tipping the proceedings over into comedy. (Euripides was comfortable enough in his comic version of Orestes’s homecoming to push farce to the point of macabre lampoon.) Still, earnest reserve has its rewards: House of Names is a novel about the modern reaching respectfully back into the past, choosing its words carefully, asking the right questions, and listening for the answers in what remains unsaid — accepting the infuriating silence of the gods.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Some enterprising theater company should stage Sartre’s existential take on Greek tragedy, The Flies. It would be interesting to see it today … in light of the Trump administration and the need for resistance. Orestes after he has murdered the King: “So you welcomed the criminal as your King, and that crime without an owner started prowling around the city, whimpering like a dog that had lost its master.”

Since I have not yet read Toibin’s new novel, I am not in a position to discuss your review, but I deeply appreciate your take on his work. Some of your insights are stunning. Your comparison between the inaction of Eilis’s in Brooklyn and that of Orestes is a sharp one — not just in terms of harm done to others, but in Eilis’s case, entrapment by circumstances. Just as she is beginning to gain some glimmer of understanding, she sinks into a sad acceptance that she has sealed her own fate.

I have thoroughly enjoyed not just your insights, but your descriptive gifts — as in “earnest reserve”, so pervasive in the tone of Toibin’s writing. And doesn’t that make him just the fellow to produce that brilliant novel The Master based on a portion of the life of the “earnestly reserved” Henry James?

So thanks again and keep writing.

DBo