Theater Commentary: Resist Trump? Boston’s Stages Opt Out

Resistance, at least in Boston theater, is futile.

A scene from the 2013 London production of “The Arrest of Ai Weiwei” at the Hampstead Theatre. Maybe dramatist Howard Brenton should have waited ten years before he wrote this?

By Bill Marx

Boston Globe theater reviewer Don Aucoin is reliably milquetoast, but his March 24th commentary, which takes up the awkwardly phrased question “What’s the Role of Theater in this Age of Trump,” was particularly soggy, even for him. Obeying the Globe‘s editorial demand that writing on the arts eschew a critical stance, he asked four talented playwrights (Anna Deavere Smith, Melinda Lopez, Walt McGough, and Patrick Gabridge) about the best way to deal with Trump on stage. The answer was — business as usual: don’t rethink, stick to liberal bromides, consider no changes. Theaters, they advise, should keep on doing what they are already (allegedly) doing well — agit-prop is beneath them. According to Gabridge, stage companies should “get beyond the knee-jerk reaction and understand the deeper humanity of what is making these things happen.” As dramatist John Greiner-Ferris mentions in a comment to the piece, the responses might have been somewhat feistier had Aucoin talked to different playwrights. (Though perhaps our intrepid critic set out to establish an inert consensus.) Of course, disagreement would have suggested there were contrary points of view in the Boston theater community, and that might have sparked lively debate. Mustn’t have that.

But energetic discussion is what is needed. Even if you bear hug the status quo, as Aucoin does, the dramatists’ responses to the coming of Trump are unforgivably tepid. They are predicated on the bogus notion that meaningful theater doesn’t sully itself by reacting to the news; it is better for playwrights to wait a few decades in order to provide humanist condemnations of political crime and corruption. In that case, I guess we are due for some ferocious indictments on stage of the Clinton and Bush administrations. The truth is that the Greeks, Shakespeare, Jonson, Ibsen, Brecht, George Bernard Shaw, Pinter, etc would have tossed off the dramatists’ hand-cuffs with a horse laugh.

Can’t we at least use the Trump ascendancy to question how our theaters are responding to the news? Or more like how they are currently not responding. Here is a task for Aucoin and those who agree that what we need is more of the same: look at the summer and fall schedules for Boston area theaters. So far, the genteel line-up more than justifies Greiner-Ferris’ charge in his Globe comment that “political theater and/or avant grade theater is virtually non-existent in Boston.” You want a revival of Man of La Mancha? You got it. (Hey, the musical will please everybody — Trump and anti-Trumpers see themselves as tilting at windmills.) Those searching for serious plays that tackle the momentous issues confronting us — climate change, growing income disparity, issues of war and peace, religious fanaticism, the curtailment of human rights (2015 was the ninth straight year of decline in global freedom as measured by the human rights watch dog, Freedom House), the empowerment of authoritarianism aided and abetted by corporate financed slavery — will have to look long and hard. Of course, many of these problems have been festering for decades. But, for some reason, efforts at ‘understanding’ haven’t made it to the American stage all that often. Are today’s playwrights afraid of taking on the tragic, seemingly intractable conflicts that attracted earlier dramatists? Can’t we question what we have been told ad nauseam — that the main purpose of theater is to generate empathy for society’s outsiders and/or victims? Or is it that stage producers (profit and non-profit) are afraid of picking scripts that force audiences to face unpleasant realities. (It is not good for branding.) Those are the kinds of questions raised by the age of Trump.

Instead, Aucoin argues that the theater’s response to what is happening to America should be more of the same — a stereotypical focus on the plight of the disadvantaged that some seem to buy as (or want to sell as) ‘real’ political theater. Aucoin neatly sums up the approach:

Playwrights who want to create work of lasting value could write dramas that tell the stories — in all their complex individuality — of those whom Trump has disparaged or who may bear the brunt of his policies: immigrants, Muslims, women, racial minorities, the disabled, the poor.

Playwrights could also create dramas that are rooted in the lives of the alienated white working-class voters who formed a major part of Trump’s base, and attempt to understand the forces that animate them. Whatever stories dramatic choose to tell, they can leverage theater’s singular status as a narrative art form that makes a direct connection to live audiences, offering a kind of two-way conversation that neither TV nor film can match.

There is much that is tired and intellectually suspect about these platitudes. Dramatists in the past had the nerve to venture into the dark heart of the matter, to examine the behavior of the powerful, not just the powerless. They explored the myriad uses and abuses of power, particularly our attraction to the kind of political/religious authority that guarantees our well-being while it masks our moral cowardice. W.H. Auden wrote that the old masters knew about suffering — they also knew who makes others suffer, and dared to point fingers and ask why. And they saw that the possibility of genuine change can only follow an act of courage — we must look at the absolute worst, face the nihilistic forces that shape ourselves and society. The Greeks, Shakespeare, Ibsen, Brecht, and the best of the moderns (Pinter, Bond, Beckett, Albee, etc) accepted that duty. They dissected the hypocrisy that is an inevitable part of our relationship to power: we worship it even as we condemn it.

Do we really need more standardized liberal scripts? More dramas that focus on the suffering of the disparaged, followed by self-congratulatory scenarios of empowerment? Deep dives into the befuddled minds of Trump supporters? That stuff is routine fodder for news on Cable TV. Dramatists should confront the intractable: conflicts involving justice and responsibility, morality and immorality, economic equity and the 1%, the digital revolution and dehumanization. Or, from the other end, how about a play that looks at the ways local activism has shaken up the powers-that-be? For example, there has been significant local kick-back around the world against corporate/government exploitation of the environment. (There are a number of noteworthy scripts that touch on contemporary issues that don’t get the time of day in Boston. I just read Howard Brenton’s fine #aiww: The Arrest of Ai Weiwei: the text takes on China, censorship, dissidence, and contemporary art. I can’t find any American productions of this 2013 script. Are our theaters afraid of pissing off China?)

The irony is that Aucoin is talking to the wrong playwrights. To my mind, the only local theater company that is reacting to the rise of Trump with the proper political panache is the Actors’ Shakespeare Project. Ah, you have got to love the Elizabethans, they knew that drama should go where the power is, not just dramatize the plight of the powerless or celebrate liberal victories. The upcoming season is an astute collection of plays about dictatorial overreachers: the modern entry is Eugene Ionesco’s Exit the King, an amusing study in the absurdity of kingship. Shakespeare’s Richard the Third and Julius Caesar are well chosen.

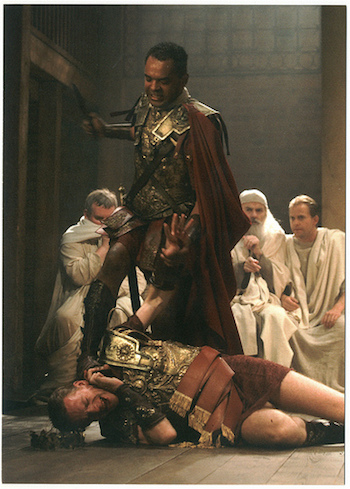

A scene in the Royal Shakespere Company’s production of “Sejanus, His Fall.” Photo: Stewart Hemley.

I would favor more outrageous fare in the future. My pick for a great play about a leader who is an out-and-out idiot? Peter Barnes’ epic The Bewitched, a Jacobean-flavored historical drama, details mindlessness at the top. And why no productions of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, a script (inspired by the power-grab of the Nazis) about a government run by gangsters? Regarding the Elizabethan period, why not take leave of Shakespeare and stir up plenty of controversy to boot? Ben Jonson’s Roman tragedy Sejanus (it is his riposte to Julius Caesar) is a brilliant study of the interconnections between dictatorship and paranoia, one of the most devastating in the history of the drama. The plot: well, imagine Trump skips off to Mar-a-Lago for an extra long vacation and Vice President Pence begins to wheel and deal in secret with Republicans and Democrats to push the barbaric but incompetent tyrant out of office. Double and triple agents, counter-plotters, and leakers become part of the mix. Trump returns unexpectedly to Washington D.C. and all hell breaks loose. In terms of garnering national headlines and guaranteed picketers, ASP should dare to stage Christopher Marlowe’s infamous The Jew of Malta — a swashbuckling anti-Semitic cartoon fantasy in which a super villain of a Jew maintains his power by pitting Muslims and Christians against each other. You know Breitbart News would cover it, big time.

Aside from ASP, the answer to Aucoin’s question about the role of theater in the age of Trump is depressing, at least for now. Boston’s stages will not be part of any meaningful resistance (aside from self-congratulatory e-mails supporting the endangered NEA). At this point, I have not even seen any plans for rabble-rousing cabarets. Jeff Zinn, managing director of Gloucester Stage, suggests one of the reasons for the passivity in the Globe piece: “I know there are people who will use the theater as a vehicle for mobilization, but I feel it is more like a church for the soul, for the mind. You come out of it feeling that culture is alive, that maybe we are renewed to fight and protest.” I respect Jeff but would his father, Howard Zinn, have accepted such a resolutely apolitical vision of theater, the kind of thing you write in applications for grants? Must the choice be either theater as mindless propaganda or as transcendent exercise room for the theatergoer’s consciousness? Protest who, what, and why? Protest everything and nothing, I guess. And in what way does Zinn’s claim reflect what is going on in the theater scene? What about all the escapist entertainment that’s staged in the Boston area? Are we talking about the holiness of Alan Ayckbourn comedies?

Just for the sake of mischievousness, let’s look at what factors determine what turns up on the theater’s church services. Resist Trump, yes, but a healthy number of the corporations and wealthy individuals who fund the arts stand to make a lot of money if the current President makes good on his plans — that he passes his huge tax cut bill for the rich, guts regulations on the big banks, lets the oil companies have their way, etc. For example, I was just in California and saw Berkeley Repertory Theater’s excellent presentation of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s production of its political drama Roe (a far, far superior script to OSF’s brain dead historical thriller Fingersmith, which for some reason the American Repertory Theater stuck us with this season). One of the supporters of Berkeley Rep is the super-giant bank Wells Fargo, which has recently reached an agreement in principle to settle (for $110 million) a class action suit generated by the bank’s practice of opening unauthorized accounts. By investing a (relatively) small amount of money in Berkeley Rep and other stages, Wells Fargo helps renovate its brand. Behind the scenes, the bank is cheering on efforts (via lobbyists) to ensure a cut back in government oversight, fewer rules that might hamper their corner-cutting, profit-making strategies in the future. Wells Fargo wins both ways — the perfect definition of the corporate American dream. Is there any surprise that so few dramas are produced that challenge the rise of the two-faced corporate consensus? That deal with income inequity? Or that question our hallowed role as consumers?

Resistance, at least in Boston theater, is futile. Aucoin argues that in “this age of Trump” we should simply accept what has been marketed as engaged theater. Even if it is just a lame substitute for the real thing that our timid drama critics, from the Globe to NPR, accept without a demur. For me, Brecht’s vision of political theater remains more salient than ever: “the radical transformation of the theatre has to correspond to the radical transformation of the mentality of our time … it is precisely theatre, art and literature which have to form the ‘ideological superstructure’ for a solid, practical rearrangement of our age’s way of life.” Of course, before our stages take on that worthy mission, they are going to have to transform themselves.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Boston-theater, Don Aucoin, Donald Trump, boston-globe

Since I was quoted in this, I want to reiterate that I do think the job of the playwright (or any artist) is to respond, whether it’s to Trump, global warming, war, whatever. I repeat: This is what I think, and I’m not saying other playwrights have to think or believe what I do. Each of us are all on our own artistic path. Others may think differently, and that’s fine. But, personally, I think what is demanded of any artist, not only playwrights, is that they should be canaries in coal mines. They should be getting upset, hurt, angered, by any event long before the masses. Isn’t that what makes us artists? That’s no easy task. You have to be way ahead of the curve. You have to throw the ball where your receiver will be. That is how you can respond to what seems to be the daily news, but you’ve been bitching about it for years. But I will say that sometimes I do wonder where, in Boston, are the radical artists that I thought, at least, we’re all supposed to be. As far as avant garde theater in Boston; yes, it’s missing, but there are a lot of things missing in Boston. A good, all-night chili parlor comes to mind. Boston theater is Boston theater, just as Washington, Chicago, Minneapolis, Seattle, or NYC each have their own brand of theater. I don’t consider my theater avant garde in the least. It does embrace, though, non-traditional elements, and it’s just my luck that there isn’t a huge audience for something like that, for artistic sensibilities that I somehow have adopted. It’s just one of the reasons I started my own company.

Thanks for this response. Theater is a big tent. There is room for all kinds of stage work. For example, there is good agitprop and bad agitprop. Years ago I saw a “Living Newspaper” production from South Africa that I still remember vividly — it unforgettably communicated the hell of apartheid. One of the problems with the soft-headed Boston Globe piece is that it came off as smug and prescriptive: of course, runs the liberal line, theater should not respond to the news — it is a church for the mind. Balderdash — theater has been many things over its history, including a way to register quick responses — angry, dismissive, supportive — to what was happening. Why hand that option for engagement over to TV or video? Frankly, what critic Don Aucoin calls ‘complex drama’ is what I would define as suburban agitprop — stories in which the marginal and downtrodden work their way to heaven — which is inevitably the middle class. Instead of this kind of consumer propaganda, critics should be demanding different forms of theater — experimental, conventional, political, etc — with various messages. The only bottom line is that the stage work be imaginative and of high quality.