Visual Arts Commentary: Urban Branding — An Expression of Civic Character

Thoughtful Branding underscores a community’s sense of place.

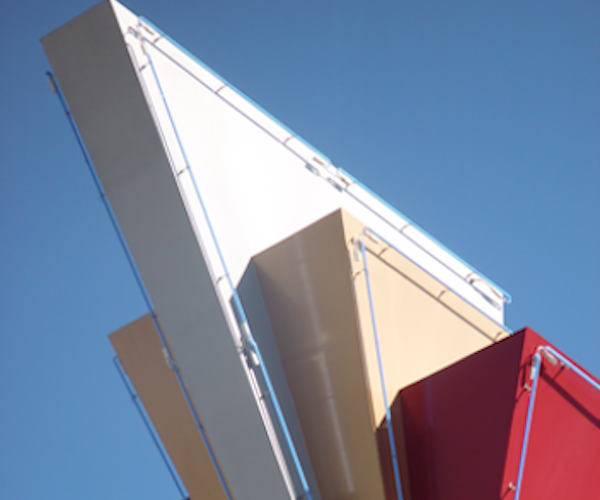

The iconic marquee for the Coolidge Corner Theatre (2002) has become an urban brand for Brookline, MA. Photo: Mark Favermann.

By Mark Favermann

Why is Paris unique? The Eiffel Tower? Avenue des Champs-Élysées? Its architecture? What makes London, London? Big Ben? Classic taxis? Red double-decker buses? Washington, D.C. trumpets ‘government’ as well as ‘nation’s capitol,’ while New York blares skyscrapers, economics, entertainment, and energy. Rome announces itself by placing its ancient structures in a modern, vital context. Through its multiple church spires, its gigantic emperor’s palace, its Czech Cubist architecture, and its quaint Old Town, Prague announces its 800 year-old patinated existence. This notion of place identity is urban branding.

Looked at through the context of design, urban branding establishes ‘image vitality’ by way of a memorable reinforcement of civic or institutional identity. Our greatest cities and regions around the world exhibit this visual energy with exuberance. Smaller towns and cities can also embrace their own community branding.

Visually and symbolically, the City of Boston is represented by the Old North Church, Old Ironsides, Boston Common, Fenway Park, The Esplanade along the Charles River and maybe Kenmore Square’s Citgo Sign, which is clearly visible from the Red Sox Fenway Park. Though a number of designers are working to effect visual community change, very few of the many suburbs surrounding Boston evoke a clear personality.

Paris Metro by Hector Guimard. Photo: Paris Metro

As the world becomes more and more urbanized, there is a clear need for a city or town to find ways to differentiate itself, to bolster its visible distinction for the sake of projecting an individual character. Public character-defining and character-building contribute to perceptions of civic pride and pride of place.

Urban Branding is the application of large-scale markers to civic environments, corporate precincts, institutions, as well as sporting and cultural events to develop identity and reinforce public image. Urban Branding is not only about logos, but can include secondary and tertiary identification elements, such as visual themes, lighting, colors, symbolism and typography. Locations for urban branding can be diverse: gateways, entrances, signage, paving, fences, public art, street furniture, monuments, landscapes, and streetscapes.

Wonderful examples of urban branding proclaim its power. Architect/Designer Hector Guimard’s Art Nouveau Metro station entrances are sprinkled throughout Paris. La Rambla, which is at the heart of Barcelona, is a pedestrian promenade that generates the joy of living. Just as the cable cars and Golden Gate Bridge illustrate and illuminate the city of San Francisco, architect Eero Saarinen’s stupendous Saint Louis Arch memorably marks the gateway city on the Mississippi River. Chicago’s magnificent Millennium Park is a gathering place for thousands throughout the year. These are grand gestures, however, there are many scaled down examples of effective urban branding as well.

Traditional London Red Mailbox, Photo: M. Favermann

The late visionary urban designer Kevin Lynch (1918-1984), in his seminal books The Image of the City and Good City Form, speculated about the idea of codifying what gives form and thus aesthetic shape and structure to an urban setting. Lynch looked at the connections between human values and the physical forms of cities.

In The Image of the City, Lynch organizes the urban area into discernable strategic elements. These markers speak to visual as well as important organizational aspects of urban recognition. Lynch addresses the physical patterning and arrangement of buildings and structures, gateways or entrance points, nodes or crossroads, focal points, and vistas. His interpretation of these five elements vary, but they form the elemental vocabulary of what he referred to as the imageable city.

As with other urban thinkers, scale is one of Lynch’s major concerns regarding urban branding. Appropriate scale is a system of measurement and harmonic proportion. Scale, in terms of the built environment, is about keeping in mind how it relates structures and forms to normal human comprehension. Size is an important way that we sense how we fit into our environment: our field of vision inevitably ranges from the intimate to the monumental.

Lynch viewed the city as three distinct theoretical constructs: (1) a cosmic (magical) ceremonial center; (2) a machine or often temporary city; and (3) a city as organism. These are the normative structures that were part of the history and growth of cities, and are ways in which each urban area could be perceived to be humane. Lynch also made use of some of these ideas when he posited the need for areas within a metropolis to proffer a distinct character; neighborhoods should have individual civic presences. In this way, Lynch’s prescient notions set the stage for the ‘science’ of urban branding.

Other provocative urban thinkers made reference to aspects of urban branding as well. In their own ways, urban critic Lewis Mumford (1895-1990), master planner Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), urban visionary Konstantinos Apostolos Doxiadis (1914-1975), and philosopher/critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) envisioned urban branding elements as tools that could enhance the urban experience.

Lexington Minute Man Monument. Photo: Mark Favermann

Urban branding both adds texture and image reinforcement to the fabric of the city. In older, more established urban areas, mostly in Europe, this infrastructure is often kept in good repair, with seamless patching and threads carefully darned. Emerging metropolitan areas demand the same need to maintain the nuts and bolts of the civic environment. Why? Because urban branding underscores a sense of arrival, a sense of shared experience–both visual and environmental. It is also about a sense of place, how it creates an particular civic experience, giving visual and even symbolic meaning to a specific location. This sense of civic responsibility underscores tourism, residential appeal, and encouraging a desired retail experience. In an institutional sense, this care establishes a strategic identity that will translate into increased image prestige and municipal brand awareness.

For example, appropriate wayfinding and signage feed into feelings of well-being and comfort in terms of safety and confidence. Branded street furniture and public art reinforce civic personality through creativity. In addition, urban branding can encourage sustainability and reinforce accessibility.

In an elemental sense, urban branding is how a civic or institutional entity defines itself. It is about the establishment of a place’s unique character of place. Think of it as applying the concept of ‘personality’ to a metropolitan area, city, neighborhood, or institution. Now augmented and reinforced by 21st century digital media, urban branding is about strategically adding comfort, visual interest, even provocative perceptual surprises to our civic environment.

An urban designer, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in community branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox since 2002. Mark writes on architecture, design, and the fine arts.

What a thoughtful piece with some great advice. I especially like the final comments “branding as strategically adding comfort” What a wonderful goal for urban planners and place making.