CD Reviews: Petrenko’s Elgar and Orozco-Estrada’s Dvořák

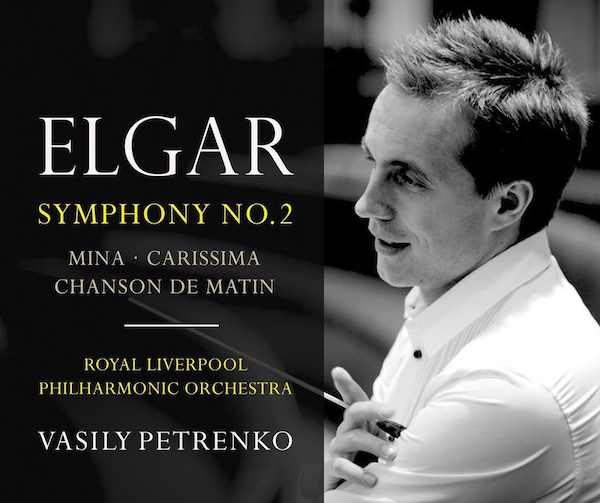

Conductor Vasily Petrenko and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra serve up some curious and, from time to time, rather languorous Elgar.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

What is it with conductors and Elgar’s Second Symphony? Nearly thirty years ago, the piece brought out Giuseppe Sinopoli’s weirdest impulses – and he was as respected, thoughtful, and musical a baton-wielder as they come. More recently, Daniel Barenboim, no Elgar neophyte, made a hash of it with the Staatskapelle Berlin. Now comes Vasily Petrenko’s take with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (RLPO) on Onyx.

A number of British critics have praised the “flexibility” of Petrenko’s tempos in this recording, especially in the outer movements. That’s one way of putting it. Another is that he likes to push things to the breaking point just before stepping back from the edge. Either way, the results are some curious and, from time to time, rather languorous Elgar.

Not that the RLPO’s playing is bad, though the brass does lack some of the heft of Previn’s Royal Philharmonic (on Phillips) and Petrenko’s interpretation doesn’t bring out the sparks Solti drew from the London Philharmonic forty-some years ago (on Decca. Then again, Solti’s in a class by himself – for better or worse). No, the orchestra plays quite responsively and wonderfully.

The middle movements, in particular, shine. Petrenko’s broad tempos mean that the glorious second one clocks in a good thirty- to sixty seconds longer than usual. But it doesn’t drag and, after all, if there’s any movement in the symphonic repertoire to simply revel in, this is the one. And, when they get turned loose (like in the blistering third movement-scherzo), the RLPO brays and dances with the best of them.

Problems, such as they are, arise in the outer movements. The big first one is a bit flabby around its middle section, which mainly serves to draw one’s attention to the music’s rather square rhythmic profile (not its most flattering characteristic). And, while broadening things out in the finale ably emphasizes the elegiac aspect of the piece once you get to the end, its first third or so has a tendency to drag and some of Petrenko’s phrasings come across as stilted.

That said, the expressive aim of Petrenko’s interpretation is fairly apparent and the RLPO is with him all the way. With the exception of some light-sounding brass at the end of the first movement, each of the orchestral families are neatly balanced and well represented throughout. The recorded sound is full and clear: you can even catch the harp writing before the second movement’s climaxes without straining your ears, not a detail every recording of this fine piece brings out.

The album’s filler is a set of three short charmers – Carissima, Mina, and Chanson de Nuit – each delicately and winningly realized.

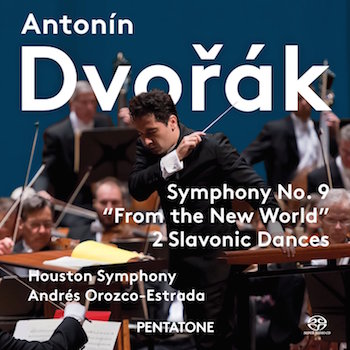

What a dud. That’s pretty much all there is to say about the final installment of the Houston Symphony’s Dvořák late-symphony cycle. While the first two volumes (covering the Symphonies nos. 6-8) offered their share of high points, this concluding Ninth falls flat.

The big problem is conductor Andres Orozco-Estrada’s interpretation. In a word, it drags. Sometimes it does so rather literally – the first and last movements are, by a half-minute or more, on the slow side – though at other times it’s more of a psychological thing: the Scherzo’s basically taken at tempo, but it’s played so leadenly that it barely registers a pulse.

Orozco-Estrada makes plenty of head-scratching decisions. His tempos are all over the map: in the first movement, for instance, he inexplicably slows things down between rehearsal numbers 3 and 5, which only serves to accentuate how lifeless his reading is. But that’s just one problem.

Rhythm is another. Where’s the impish, dancing wit of the Symphony’s many syncopated figures? They’re largely absent here. Indeed, it’s never a good sign when the first movement’s introduction has all the rhythmic character of a wet rag. Or when the lovely slow movement all but puts one to sleep. Or when the galloping figures that introduce the finale’s second theme lack any tension whatsoever.

You get the idea. Indeed, this must be one of the most unnecessary recordings of a canonical staple in recent memory. Even some fine woodwind and brass solos from the Houston Symphony’s principals can’t redeem it. Ditto for the two Slavonic Dances (nos. 3 and 5 from the op. 46 set) that round out the album.

Pentatone’s sonics are typically clear and rich. In this case, though, that doesn’t help things.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andres Orozco-Estrada, Houston Symphony, Onyx, Pentatone, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra