Book Review: “With Ballet in My Soul” — The Vicissitudes of an Impresario

Eva Maze drops names, to be sure, and paints a heady picture of the high life, but she does so with the disarming charm that permeates most of her memoir.

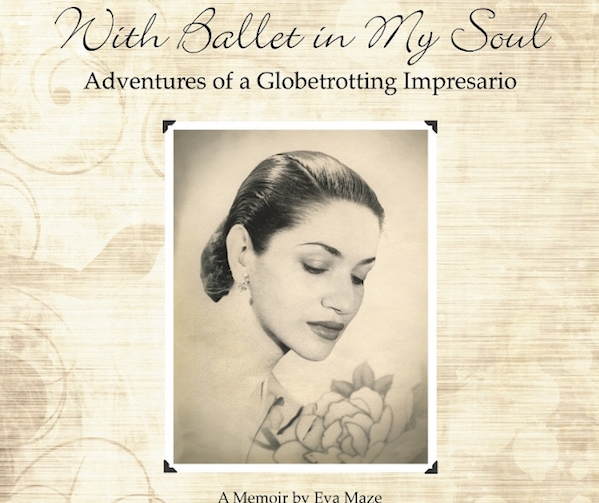

With Ballet in My Soul: Adventures of a Globetrotting Impresario by Eva Maze. Moonstone Press LLC , 200 pages, $24.95, paperback.

by Janine Parker

Soon into nonagenarian Eva Maze’s memoirs it becomes clear that — despite her title — ballet will not be the main dish on the menu. Although she first fell in love with ballet as a five year-old child, a nearly fatal bout of scarlet fever at age seven led her parents to forbid her anything physically strenuous; alas, dancing, for poor little Eva, was out. Thus, as Maze tells us on the third page, “it would be another 13 years until I returned to my early love of ballet class…by then I knew it was too late for me to have a professional career as a ballet dancer…”

If that confession several pages in is akin to burying the lede, the book’s subtitle — “Adventures of a Globetrotting Impresario” — comes off as wry understatement. Maze, née Feldstein, was born in Romania in 1922; by the time she was sixteen, she and her parents had moved to the United States. Ironically, the overseas trip was only meant to be a visit. An only child whose parents were perhaps more prone to doting after her illness (as the author admits, she was “…their precious (and somewhat spoiled) daughter…” ), young Eva convinced her parents to take her to the 1939 World’s Fair, hardly an easy journey in those days, even for a financially comfortable family such as the Feldsteins. In any event, off they went, from Bucharest to Chicago, via an illuminating stopover in Paris, where the physical beauty and cultural wealth of the French city left an indelible imprint on her impressionable teenage spirit. Once in America, the family stayed, settling in Brooklyn. World War II was now underway and New York was a better bet than their homeland: “Had we stayed, we might have been among the 300,000 Romanian Jews and gypsies who were eventually deported to the concentration camps.”

Though she writes fondly of her Bucharest childhood, Maze’s resilient sensibility and precocious thirst for new experiences led her to embrace her new life. Finishing up high school early, she decided to delay college. (When she did go, she majored in psychology, but she was also able to further her romance with dance, studying modern dance and composition at Barnard.) In the interim, she worked part time and attended night school, where she took business courses and learned Spanish and Portuguese. That made it an impressive eight languages that Maze knew “…rather well.” She landed a job as a translator in the radio broadcast division of a state department agency set up during President Roosevelt’s administration. (Eventually she took a course on radio program directing, and years later produced some radio programs of her own in India.)

A photo of Eva Maze dancing in a page from “With Ballet in My Soul.”

All of these experiences and skill sets — exposure to a myriad of cultures, command of multiple languages, office work, production knowledge and, of course, her early and lifelong love of dance, helped her in her future job as an arts presenter, or impresario. The latter is the title she prefers; it is associated with the legends Sol Hurok (an inspiration to Maze) and Sergei Diaghilev. The word’s old-world flavor certainly suits the era in which she came of age, and hearkens back to a time when, for many, the performing arts seemed both “exotic” and revered, something precious.

When she finally made her way back to the barre, she was twenty years old, newly enrolled in college, and newly married, too. Her husband, Oscar Maze, and his family were also emigrés to the U.S., Polish Jews who likewise probably escaped extinction by coming to America. A member of the Air Force, Oscar, who had to give up his dream of becoming a pilot because of his imperfect eyesight, nonetheless spent his entire working life in aviation, climbing aboard the growing Pan Am enterprise in 1946 and remaining an employee of the company until it was bought out in 1991.

Oscar’s job meant that the couple, who eventually had two daughters, Stephanie and Lauri, were not only able to travel extensively, but also had to pick up and move their family several times over the course of their five decades together. Iowa, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania — where Oscar’s various Air Force assignments brought them — were just baby steps compared to the leaps from London to New Delhi to Berlin. Embedded in their series of homes for years-long periods, the couple also managed run-outs even further afield — often at the suggestion or invitation of the numerous fascinating individuals the pair met along the way. Indeed, it seems that wherever they went the Mazes added new figures to their growing A-list of acquaintances, which included ambassadors and royals.

Eva drops names, to be sure, and paints a heady picture of the high life, but she does so with the disarming charm that permeates most of the book. Years and even decades glide smoothly by, while Eva writes of her Forrest Gump-like penchant for being present at historic moments. These range from the joyous to the somber: a brief visit to Kathmandu coincided with Edmund Hillary’s and Tenzing Norgay’s famously successful climb to the top of Mt. Everest, whereas one of Eva’s biggest gigs — producing a major folkdance festival for the 1972 Munich Olympics — was scarred by the tragic hostage crisis, in which eleven members of the Israeli team were killed. She found herself living or working in Berlin when the Wall began to go up in 1961 and when it began to come down nearly three decades later.

If Maze’s name isn’t familiar to you (as it wasn’t to me) that’s perhaps because her business — Eva Maze Presents/International Artists Productions, officially launched in 1954 — was largely an overseas concern, with the bulk of the performers and events she presented appearing throughout Germany. Many of the individuals and companies she engaged are themselves widely known, and reflect both her eye for talent and her tenacious ability to secure it. The relative obscurity of her name, however, reflects the inevitable behind-the-scenes nature of presenters. The surface glamour of hobnobbing with luminaries such as Mikhail Baryshnikov aside, the details involved in arranging international tours are, not surprisingly, copious.

Pages from “With Ballet in My Soul.”

Maze errs on the side of graceful diplomacy when it comes to talking about her star-studded roster. But there is an occasional note of exasperation, ironically having to do with dancers. The first time she produced a tour — at the request of the great ballet teacher Ludmilla Schollar — Eva brought three dancers and their accompanist to India. The experience showed her “just how complicated it could be.” She’d learn how to “deal with different types of personalities and egos,” but she told herself that she’d “never tour with another dancer again.” Of course, she did continue to present dance programs of a wide variety, but the genre seems to have always been a challenge. When explaining a “typical” day in a tour, Maze writes that “the schedule was often grueling, though the actors seemed to adjust to it better than, for example, dancers…” The predictable tension is the result of the clash between the presenter’s eye on the bottom line and the performers’ comfort levels. For some, it just didn’t sit well: “…the tight touring schedule was met, at times, with resistance, as with the Alvin Ailey [American] Dance Theater and Lar Lubovitch Dance Company.”

It could be, given these comments, Maze regretted the derailment of her career as a professional dancer more than she realized. Perhaps; she takes the time to mention that when she performed a mostly character role (in a production of Sleeping Beauty) her daughter Stephanie “…thought I was a better queen than the dancer” who replaced Eva in the role. While Maze’s voice in the book comes off as confident rather than arrogant, she can be a bit tone-deaf, as when she chronicles her initial forays into learning the various styles of Classical Indian dance: “I didn’t find Indian dance difficult and seemed to follow the choreography without too much effort.”

Mostly, however, Maze is justifiably proud about her work; it’s exhilarating to read about a woman who led such an independent and successful life during a time in which her field was mostly male-dominated. As she tells it, she met most of her trade’s unforeseen yet inevitable snafus with quick thinking and good humor.

On its website, Moonstone Press (founded by Maze’s daughter Stephanie) states that the company publishes many children’s books. With Ballet in My Soul is creatively designed, with photographs and reproductions of posters elegantly scattered throughout the book. It’s a pleasant read that is both a moving homage to the lovely sense of tradition engrained within the performing arts as well as a primer on why internationalism matters, why “culture” isn’t a forbidding, somehow elitist activity, but should be available to all, a crucial key for opening up minds.

Noting the ways in which, after World War II, many western European countries “…expanded their citizens’ access to culture,” Maze reflects that “…with monies levied from personal taxes, they developed social institutions and public policies that supported culture and arts endowments…As a result, the public became very receptive to new ideas in the performing arts and other art forms…” It is impossible to read this without thinking of our own country’s often ambivalent support of the arts; at this point, the National Endowment for the Arts may be taken to the chopping block. This makes With Ballet in My Soul more than just a lovely gift to send to one’s childhood dance teachers. It should be mandatory reading for politicians who need to recognize their responsibility for supporting the arts.

Janine Parker can be reached at parkerzab@hotmail.com.

Tagged: ballet, Eva Maze, impresario, Janine Parker, Moonstone Press