Film Review: Marcel Pagnol’s Marseille Trilogy — Three memorable Creations: “Marius” (1931), “Fanny” (1932), and “César” (1936)

Marcel Pagnol’s great Marseille Trilogy is a tragicomic love story set on the bustling, sun-drenched docks of a Mediterranean port.

Marcel Pagnol’s Marseille Trilogy: Marius (1931), Fanny (1932) and César (1936). Screening at the Kendall Square Cinema, Cambridge, MA, through March 16.

By Betsy Sherman

A three-part wonder of 1930s French cinema is back in theaters after a digital restoration supervised by the Cinémathèque française. Marcel Pagnol’s Marseille Trilogy bears the names of a trio of unforgettable creations: Marius (1931), Fanny (1932) and César (1936). These protagonists are surrounded by a colorful bunch of supporting characters as they play parts in a tragicomic love story on the bustling, sun-drenched docks of the Mediterranean port. The sensual tale of love, loss, and family intrigue is also an occasion to enjoy some primo clowning by actors bred in the early 20th-century music-hall tradition.

That span of production time, 1931-1936, wasn’t only noteworthy in the life and career of Pagnol, who ascended in stature from a new voice in Parisian theater to a film author-producer-director with a worldwide audience. This was a time of dramatic change in French cinema. The advent of the sound film at the end of the 1920s coincided with a French film industry in disarray. The two big studios of the silent era, Pathé and Gaumont, were in the midst of restructuring. This left room for the Americans and the Germans to step in and take over a good chunk of French talkie production (the rival recording systems were Western Electric and the Germans’ Tobis).

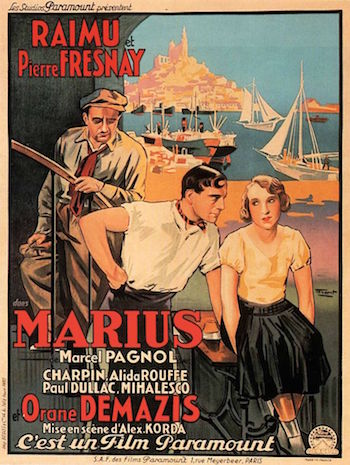

The beginning of the saga, Marius, was made for Paramount Pictures’ affiliate in France. There, as in the U.S., the studios turned to the theater for dramatic properties and performers. Daring in its undiluted regional setting, Marius had been a sensation on the Paris stage in 1929 (Pagnol was born in Aubagne and grew up in Marseille). Paramount’s director of operations in France, Bob Kane, approached Pagnol to buy the film rights. Enthusiastic about the potential of talkies, Pagnol charged into the negotiations with nerve: he wanted to direct. Kane insisted on a director with a track record, and tapped Hungarian émigré Alexander Korda (who had directed in the U.S. and would go on to an important career in Britain). But he agreed to Pagnol’s demand that the play’s cast, though inexperienced in front of the camera, could repeat their roles. Some accounts say that Pagnol deserves co-director credit for his part crafting the film version of Marius. Korda, as it happened, had triple duty, also directing, as was common practice for a few years, alternate-language versions with alternate casts—in this case, German and Swedish. For Pagnol it was the first dip of a toe into what would be a spectacular filmmaking career (for me, his masterpiece is The Baker’s Wife).

The film right away winks at its Southern setting: two main characters are caught mid-siesta. Working (hardly) is Marius (Pierre Fresnay), behind the bar at his napping father César’s Bar de la Marine. The dissatisfied-looking 22-year-old stands in front of the iconic setting that anchors the trilogy: the bar’s wall of bottled spirits (a notion to be taken literally and figuratively). Marius suffers from a “madness for the sea,” which is so near, yet, considering his obligations, so far [warning: some spoilers will be revealed while proceeding with descriptions from film one to two to three].

Marius being an early sound film, it is necessarily studio-bound (at the Paramount studio at Joinville). However, there are some exteriors in Marseille, including establishing shots that set up another important metaphor, of its harbor as womb. Female anatomy will take over later in the story, but in this opening chapter this theme ties in with explorations of manliness and ambition. Marius is bewildered by his father’s pal, Captain Escartefigue (Paul Dullac), whose boat traverses the harbor 24 times a day and who has no desire to cross the threshold into the wider sea. Boats that go far, he cautions Marius, “also go deep.” Yet in spite of his prudence in staying close to home, he’s a well-known cuckold (even the roly-poly captain knows it).

With this film, Pagnol and Korda paint a world. Its most colorful, and certainly loudest, presence is the widower César (played by the hilarious Raimu, man of a zillion facial expressions). The bar owner’s hair-trigger temper and know-it-all brio are leavened by tender moments (he’s hard on Marius, but at one point concedes, “When I say you poison my existence, it’s not true”). His circle of cronies banters and bickers in wonderfully percussive Marseille dialect—except for Monsieur Brun, the contrasting outsider from Lyon who speaks with crisp diction (their bridge game, full of audacious cheating, is a comic highlight). But there are also glimpses of the transitory maritime element, as when Marius makes a furtive visit, past sailors and hookers, to a shadowy bar in which darker-skinned people speak different languages and play exotic music (these enticing outsiders aren’t seen after Marius, so they may reflect Korda’s touch).

Central to the trilogy is Fanny—a role written for the remarkable Orane Demazis. The bright-eyed eighteen-year-old daughter of widowed fishmonger Honorine (the deftly comic Alida Rouffe), Fanny runs the shellfish concession. All she has wanted to be, for as long as she can remember, is Marius’ wife. But she hasn’t confessed her love to him, and he has made no move towards her. With a modicum of cunning, she flaunts the fact that the recently widowed 50-year-old sail-maker Honoré Panisse (Charpin) has proposed to her, to test whether Marius seems jealous. It works, and the young pair become lovers, but how is Fanny to compete with Marius’ compulsion, when the sea is in front of his eyes, his ears (he can identify the ships’ whistles) and his nose?

Central to the trilogy is Fanny—a role written for the remarkable Orane Demazis. The bright-eyed eighteen-year-old daughter of widowed fishmonger Honorine (the deftly comic Alida Rouffe), Fanny runs the shellfish concession. All she has wanted to be, for as long as she can remember, is Marius’ wife. But she hasn’t confessed her love to him, and he has made no move towards her. With a modicum of cunning, she flaunts the fact that the recently widowed 50-year-old sail-maker Honoré Panisse (Charpin) has proposed to her, to test whether Marius seems jealous. It works, and the young pair become lovers, but how is Fanny to compete with Marius’ compulsion, when the sea is in front of his eyes, his ears (he can identify the ships’ whistles) and his nose?

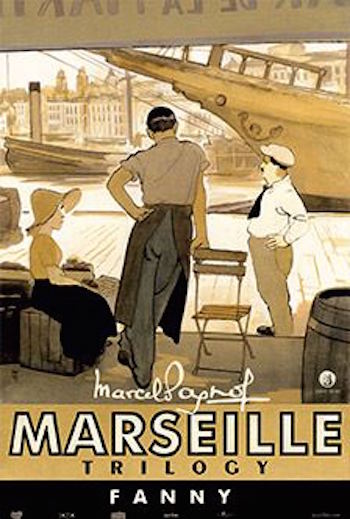

Marius was such a hit that Pagnol quickly wrote a continuation, Fanny, and put it onstage. He’d had a spat with Paramount, so the film adaptation was made by his own production company, and directed by Marc Allégret. Happily, there’s more of Marseille on display here than in Marius. Demazis does indeed shine in this installment named after her character, but the picture is stolen by Charpin, as Panisse transforms from a figure of fun in Marius into an eloquent, open-hearted mensch.

Fanny begins directly after the end of the first movie, on the day Marius decides to “marry the sea” and signs on to a ship embarking on a five-year scientific expedition to Australia. César too is crushed. There’s a shot that begins movingly with Fanny embracing her almost-father-in-law; the mood turns somber as César advances, trudging, towards the camera, which retreats to give him space. Life continues—in familiar settings of the bar, Fanny’s home, and Panisse’s shop—as those who love Marius await any scrap of news from him. Then, suddenly, we’re in new territory: Fanny exits a doctor’s office and walks, not on the set we’ve come to know, but down real city sidewalks, past stores, banks, and busy people. First she drifts, then strides with purpose. She mounts a stone stairway, giving us a view of the city and the harbor. She enters a church and kneels. She’s pregnant, and begs, “Holy Mother, forgive me …. Give me the strength to live.”

An emotional scene follows as she tells her mother and aunt. Honorine vows to throw Fanny out, but once she’s calmed down, she orders Fanny to accept the renewed offer of marriage from the prosperous Panisse—who can be fooled into thinking the baby is his. Fanny agrees to go to Panisse, but to tell him the truth, and see if he will still have her. Next comes the beautifully written, beautifully acted scene in which Fanny proves again that she’s a woman of principle, and Pagnol gives us new insight into Panisse while staying true to the marrow of the character as previously played. This chunk of the story doesn’t end there, and Demazis shows us that Fanny’s heart is a more complicated place than the trappings of her new, more comfortable life would suggest.

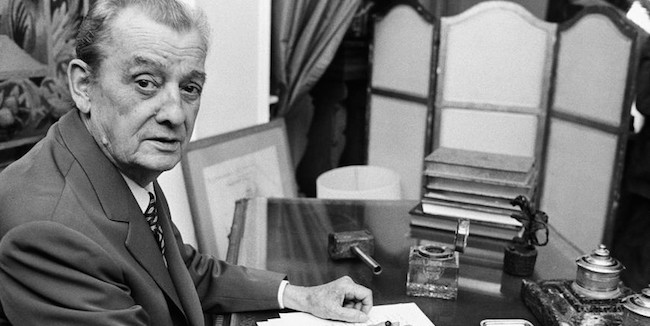

French novelist, playwright, and filmmaker Marcel Pagnol.

The sequel did well, though it didn’t generate the sensation of Marius. In its wake, Pagnol began his directorial career, and left behind these people of the docks. In 1935, a colleague broached the subject of another chapter to the story. However, according to Pagnol, the plea that got him to envision a trilogy came from a nice old lady who said she didn’t want to die without knowing how things turned out. Pagnol set this original screenplay close to 20 years after the end of Fanny (contrary to practice, he turned this screenplay into a stage play after shooting the movie). Another pertinent development in between the making of Fanny and César is that Demazis and Pagnol had a child out of wedlock. Plus, he had babies out of wedlock with two other women (as, er, research?).

The title César would suggest that the formidable Raimu is the prime focus. He flexes his big personality alright, but the title also refers to the son of Fanny and Marius—who has been thought by all but a few to be the son of Fanny and Panisse. Known by the diminutive Césariot, the young man, now 20, is doted on by César as godfather, not grandfather. This is a story of transitions, with an internment followed by the unearthing of difficult truths, and the examination of long simmering resentments. Over the course of a sometimes bumpy narrative of almost two and a half hours, events move toward forgiveness and regeneration.

César is fully a Marseille production, reflecting the realization of Pagnol’s dream of a Provençal industry. To denote the passing of time, the auteur does more than make Raimu’s hair gray. Quite noticeable during the first significant interior scene is the traffic noise coming from outside. The presence of automobiles denotes the sped up pace of life (since it wasn’t a thought-out trilogy, the first two parts did not take place in the 1910s, although their relative minimalism does make it seem like they were in simpler times). There’s an implication that something is in the process of slipping away, and as soon as Fanny—a bit filled out, and better dressed than in her youth—brings home her son from the train station, that becomes apparent. Césariot is home from the Polytechnic School at which he boards (he’ll go on from there to the army). Without much warning, his world will turn upside down, as he learns about his origins, and struggles to put this knowledge into perspective.

Pierre Fresnay and Orane Demazi in a scene from “Marius.”

César is a bracing take-in, peppered with some of the old shtik and slapstick but also tinged with melancholy and exhibiting, at times, a sense of alarm. It’s a shocker when Césariot starts to speak, without any trace of a Marseille accent. His arrival was so highly anticipated by so many people in Fanny, it’s odd that he seems to have been exiled in the name of a good education from a milieu that has been depicted as so soul-nourishing. The movie doesn’t really address this, so it seems a case of the bourgeois dream being something that must be accepted. The actor playing Césariot, André Eugène Fouché, is something of a wet rag. Was the lack of charisma for this new generation intentional? I couldn’t help but pity the character.

Marius re-enters the story in a substantial way, and it’s in César that actor Pierre Fresnay finally comes into his own. In Marius, his performance was difficult to accept. It could be a case of vantage point, since he’s better known for subsequent upper class—David Niven-ish, really—characterizations, such as the aristocratic officer in The Grand Illusion. It could be that he was too old at 34 to be a dreamy youth; he played Marius’ anguish, but not his joy. The erstwhile mariner of César is damaged and disappointed. He chose adventure, but came to regret it. Fresnay, his age now an asset, sinks his teeth into the chance to play a man who may get a second chance, but doesn’t know if he deserves it.

The touching final scene takes place in the full bloom of nature. Not surprisingly, César gets the last word; he quotes for Fanny and Marius from the “engineer’s logic” of Césariot, ensuring the representation of all generations. But the parting waggle of the eyebrows is his and his alone.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.