Book Review: “Cursed Legacy” — The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann

Despite its flaws, Cursed Legacy‘s chronicle of the life of Thomas Mann’s son is an important addition to the cultural history of the twentieth century.

Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann by Frederic Spotts. Yale University Press, 352 pages, $40.

In the last uneasy weeks of the Clinton-Trump presidential campaign, as friends talked about emigration, I was reading Frederic Spotts’ Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann. This jam-packed biography by independent scholar and author Frederic Spotts (Bayreuth, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics) examines in detail why one very complicated German writer decided to leave Germany in the 1930s, how he did it, and what happened to him in emigration and his eventual attempt to return home.

Klaus Mann (1906-1949), first son of world-famous Thomas Mann, was one of the earliest and youngest writers to publicly oppose Nazism. By 21, he was known as a playwright, performer, journalist, editor, novelist, essayist, and lecturer. He was also an out homosexual, budding drug addict, and manic depressive, who died in ambiguous circumstances in the south of France at 42.

“Writing was what kept him going,” Spotts maintains about the man he treats both as a fascinating case study and prototype of a twentieth century European intellectual. “He began at the age of six with a poem he gave his father one breakfast-time and then never stopped … ‘I am reasonably well: I am trying to write,’ are the words he put down in a letter to his mother and sister Erika just hours before he died.”

Klaus was the second of the six children of Katia Pringsheim and Thomas Mann, who published his first novel, Buddenbrooks, while he was in his mid-twenties and would win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929. His household in Munich, like Sigmund Freud’s in Vienna, was organized to suit the needs of its resident genius. Katia Mann could be counted on to protect those needs, but Klaus was fortunate to have the emotional support of maternal grandparents, his writer/activist uncle Heinrich Mann, his beloved sister Erika (older by one year), and such sympathetic neighbors as conductor Bruno Walter, his wife and two daughters. Unlike Franz Kafka, Klaus never wrote his father a comprehensive letter making explicit his complaints. It would have been encyclopedic.

Thomas was not only a powerful and narcissistic author who kept an eye on his royalties, reputation, and the competition, but a tightly closeted homosexual who regarded his son as an embarrassment. Klaus, on the other hand, was a wild child, a beneficiary of a progressive education who never made secret his infatuations with boys.

The six Mann children were all what today would be called “trust fund babies,” whose monthly stipends allowed them to follow their bliss and cash in on the family name as soon as they came of age. His older sister Erika chose to live in Berlin when she was 18 and to study under the renowned theater director Max Rheinhardt. In September of 1924, just before he turned 18, Klaus followed Erika to Weimar Berlin.

There, Klaus got a job as a local newspaper’s assistant theater critic and wrote more than 30 reviews in five months. His literary output might be termed manic. First, he made a splash writing Anja und Esther, the first German play about homosexual life, in which he co-starred with Erika and another child of a prominent father, Pamela Wedekind. Adding insult to injury in the eyes of his father, Klaus published Der fromme Tanz, what Spotts terms “the first openly gay novel in German literature.”

In an often breathless 311-page narrative, which reads as though it’s bursting at the seams, Spotts tracks many other rich themes while never losing sight of the painful father-son leitmotif. He keeps us apprised of Klaus’ hundreds of publications, travel routes, love affairs and one-night stands, his passionate entanglement with his sister, his friendships and disappointments with prominent mentors such as André Gide, Jean Cocteau, and Stefan Zweig — who once told him “Go ahead, young friend. There may be prejudices against you because of your famous parentage. Never mind! Say what you have to say.”

Spotts tries to juggle all of these topics as his narrative moves from Klaus’ adolescence through the 1930s, as Klaus becomes a Cassandra-like figure, forecasting the coming disaster and Hitler’s corruption of European cultural life. He also keeps his eye on his protagonist’s attempts to self-medicate and struggle with the drug addiction that eventually killed him.

Given the overwhelming amount of biographical material and Klaus’ own extensive writing about his childhood, Spotts chooses to skim the early years and dig in with Klaus as a young man in Weimar Berlin. By the time he was 28, Klaus had published “no fewer than four plays, three novels, three volumes of short stories, an autobiography, over one hundred essays, reviews and reports, two anthologies (one prose and one poetry) and, in collaboration with Erika, two travel books.”

By the age of 21, Klaus was familiar with most of the major cities in Europe. In 1928, he set off on a globe-trot with Erika. Billing themselves as “the Mann twins” when they docked in New York, they lectured across the U.S., and visited family friends on their way to the German-emigré colony in Hollywood. From there, they traveled to Japan. Korea, and the Soviet Union.

What he saw and heard during that world tour helped crystallize Klaus’ response to Nazism. After the Reichstag elections of September 1930, when the Nazis increased their seats from 12 to 107, and moved from 800,000 to six and a half million votes, Klaus became obsessed with what he saw an impending disaster.

“Anyone who was apathetic about politics yesterday was certainly shaken up,” he declared in a speech in Vienna a few weeks later. After Stefan Zweig published an article claiming that democracy was ineffective and young people were voting for Nazis in protest, Klaus wrote in response: “I want to have nothing, nothing at all to do with this perverse kind of ‘radicalism.’ I cannot help preferring the slowness and uncertainty of the democratic process to the devastating swiftness of those dashing counter-revolutionaries.”

Spotts points out that Klaus, unlike more cautious writers, had intimate access to the new Nazis. One of his working-class lovers appeared one day in a stormtrooper’s uniform and said, “They are going to be the bosses and that’s all there is to it.” It’s unclear how soon the Manns began considering emigration. They had good reason to remain in Germany, but “as early as mid-1931 they discussed having to flee.” Spotts quotes from Klaus’ diary of November 19: “‘Bruno Walter at dinner. (Discussion about Nazis. Possible governments. Emigration.)’”

The Mann family did not, however, leave immediately. It wasn’t until two years later, in March of 1933, when Hitler was Chancellor, after the Reichstag fire, and after the family chauffeur warned Klaus and Erika (returning from a ski trip in Switzerland) that they were in danger of arrest, that they fled. While Thomas and Katia Mann chose Kusnacht, Switzerland as their refuge, Klaus made a Left Bank hotel in Paris his base as he continued his travels. His siblings scattered.

“Roughly one hundred thousand Germans fled to France,” according to Spotts, and were regarded “not as unfortunate refugees but as highly unwelcome intruders … Some assumed that, being German, he was a Nazi. Speaking German in public, he soon discovered, risked being insulted and even spat on. The great majority, however, found it incomprehensible – even suspicious – that a decent citizen would renounce his homeland.”

Klaus’ chief concern was to find a German-language publisher. He was fortunate to meet Fritz Landshoff, a German Jewish publisher who had fled to Amsterdam and was publishing émigré authors under the aegis of Emanuel Querido. Klaus signed with Querido Verlag, became one of the 15,000 German émigrés resident in Holland and, with Querido’s backing, started Die Sammlung, a journal of emigré writing. He worked energetically as its editor while writing Flucht in den Norden, what Spotts calls “the first German exile novel,” with a political heroine at its center.

In the spring of 1934, Klaus’ German passport expired and the peripatetic writer was forced to renew temporary travel documents every six months until the President of Czechoslovakia offered citizenship to the entire Mann family in 1936. Astoundingly, despite his statelessness and his growing substance abuse, neither his pace of travel nor publication slowed.

In 1935, in addition to his many short pieces, he completed Symphonie Pathétique, a novel about Tchaikovsky, with whom he identified not only as a cultural outsider but as a gay man. In 1936, inspired by De Maupassant’s novel of an opportunist, Klaus wrote the novel he is now best remembered for. Mephisto: Novel of a Career is the story of Hendrik Höfgen, an opportunistic performer during the Nazi period that draws on the biography of Klaus’ ex-friend and Erika’s ex-husband, actor Gustaf Grundgens.

Most literate Germans were aware that Gestapo founder Hermann Goering had seen Grundgens perform the role of Mephistopheles in Faust, and was so impressed that, in 1934, had offered him the directorship of the Berlin State Theater.

In Klaus’ novel, the protagonist’s initials are HH but the references to GG were clearly understood. The book could not be published in Germany until 1956 and even then was subjected to legal action and banned until it was made into a 1981 film directed by István Szabó and starring Klaus Maria Brandauer as Hendrik Höfgen. Spotts points out that “some four thousand actors and others in the theater had fled Germany, accompanied by 1500 writers and playwrights. Many of those not fortunate to get out died in concentration camps or committed suicide … Ultimately Mephisto is a monument to Klaus’ single-minded commitment to combating Nazism.”

Using his Czech passport, Klaus continued to travel frenetically, writing as he went. In Budapest to treat his drug addiction, he fell in love with a young American. He then crossed the Atlantic to lecture in the U.S. and went with Erika to Spain as a reporter on assignment for several publications – all this while working on yet more books. His novel Der Vulkan, published by Querido in May of 1939, is among the most famous books about German exiles during World War II. But the narrative did not please many exiles at the time; Spotts argues that it was because Klaus didn’t limit his cast of characters to “respectable” refugees but included drug addicts, homosexuals, and anarchists. Querido printed 3000 copies and sold only 300. American publishers were uninterested. The followig year, when Hitler invaded Holland, the Nazis closed Querido Verlag. His Dutch (Jewish) publisher died in Sobibor.

By that time, the Manns had emigrated. Their Czech passports were rendered useless after Hitler’s annexation of the Czech lands. A prominent sponsor found Thomas and Katia a house in Princeton, N.J. around the corner from Albert Einstein and an easy teaching gig. Although slow to denounce Hitler, he had become the dean of the German émigrés. He and Katia applied for American citizenship, while 31-year-old Klaus was once again an undocumented alien.

He had contracted syphilis, and underwent a painful treatment, but saw his major challenge as learning to write in a new language. He stopped reading and writing German. “The writer must not cling with stubborn nostalgia to his mother tongue,” Spotts quotes from The Turning Point: 35 Years in this Century, which Klaus wrote in English and published in 1942. He must “find a new vocabulary, a new set of rhythms and devices, a new medium to articulate his sorrow and emotions, his protests and his prayers.”

The book received excellent reviews, but sold less than a thousand copies. Alone, broke, at loose ends professionally, he was determined to join the army as soon as he became a citizen – a process that was delayed because of FBI inquiries into his relationship with Erika, and his sexual and political activities. But in February of 1943 he did his basic training in Arkansas and wound up interrogating German deserters and prisoners of war in Italy in the wake of the American occupation.

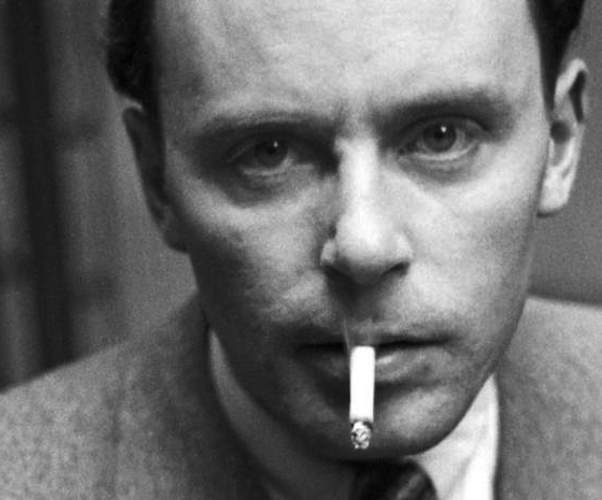

Klaus Mann — a very complicated German writer. Photo: Yale University Press.

He found old friends and new lovers in Rome and remained in post-war Europe as a reporter for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, for which he wrote some 90 articles, including interviews with prominent European cultural figures who had survived or collaborated with the Nazis.

His return to Germany was painful and impossible. In May of 1946, in Berlin, Klaus went to the theater to see Gustaf Grundgens, recently released from the Soviet Union. “He had given up everything when he fled from Munich in 1933,” Spotts observes. “For a dozen years he had fought Nazism in every way he knew. Now he was homeless, almost penniless and unknown. And there on stage was a triumphant Grundgens. He had served the regime. He had been the darling of its supreme leaders, was prosperous, admired and famous. This was no longer Balzac, it was Shakespeare at his blackest.”

Klaus ended his life in the south of France in May of 1949, “writing going badly, financially bust, addicted to morphine, lonely beyond words, pained by a political world moving in a direction that was opposed to everything he believed in … Erika – his emotional center, rock, anchor and ultimate friend – even she had fallen away.” It has never been determined whether his death was an accidental overdose of sleeping pills or a suicide.

This memoir absorbed me and made me feel for the biographer as well as his subject. Spotts was faced with an embarrassment of biographical riches and I felt he often struggled to organize and balance his volatile material. This volume needed more careful editing and additional drafts. For example, the chronology of events is often needlessly confusing. It’s often up to the reader to figure out exactly where Klaus actually is and how he got there, who a minor character is and when we last saw him or her. The Yale University Press edition is a reprint of the UK edition — it features British punctuation, usage, and vocabulary. Spotts’ writing is fluent but sometimes slapdash, much like Klaus Mann’s own prose.

Despite these flaws, Cursed Legacy is an affecting biography and an important addition to the cultural history of the twentieth century. It made me want to read Klaus Mann’s books and his journalism — particularly those 90 articles he wrote for Stars and Stripes. It offers up a feast for thought — even if Spotts bites off more than he can chew.

Helen Epstein is a writer of non-fiction. Her books as well as many books by Central European authors can be found at Plunkett Lake Press.

Tagged: Culture Vulture, Cursed Legacy, Frederic Spotts, Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann