Film Review: “Eight Days a Week” — A Marvelous Look at The Beatles on Tour

Unlike any other Beatles documentary, this one succeeds in graphically presenting the hysteria of the few years when the band played live and toured the world.

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years, directed by Ron Howard. Begins screening at the Coolidge Corner Theatre, Brookline, MA on September 15. It will start streaming on Hulu on September 17.

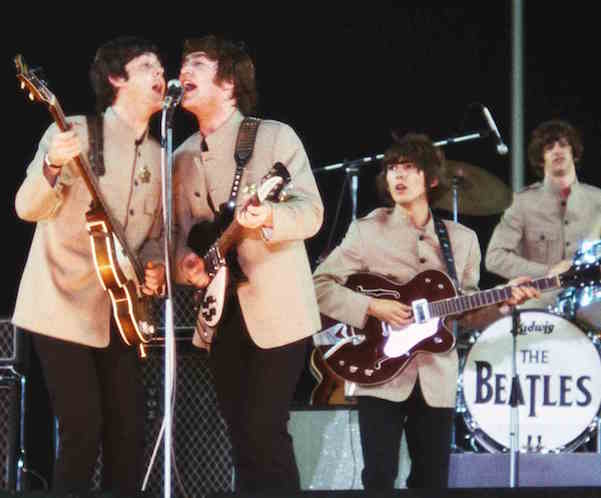

A scene from “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years.”

By Tim Jackson

Ron Howard’s new documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years begins with one word — “Ringo.” On the screen we see the legendary drummer’s Oyster Black Ludwig drum kit, stenciled with famous Beatles “drop-T” logo. “In the beginning it was so easy,” muses the drummer. We’re poised for a trip down memory lane or, if you were born after 1960, for a galvanizing lesson about one of the most formidable musical phenomena of the 20th century. Unlike any other Beatles documentary, this one succeeds in graphically presenting the hysteria of the few years when the band played live and toured the world. Testimonials also make clear the enormous cultural and musical significance of these early days. As African-American comedian Whoopi Goldberg attests: “We never thought of them as white guys, they were the Beatles. That I could do things the way I want to, I got from them.”

Beyond rallying together an entire post-war generation, inspiring a million young musicians, igniting the creativity of songwriters and producers and changing the face of popular music, these were four young men firm in their commitment to one another and the band. They had to be: the group was quickly overwhelmed by a tsunami of popularity. The filmmakers have digitally refreshed an amazing amount of footage. The gathering includes: concerts from around the world; shots of hordes of fans queuing all night long in mile long lines for tickets; teenage girls out of control, swooning, passed unconscious at stadium concerts; the press relentlessly questioning the band members about their motives and staying power. The boys carry on through the firestorm with dignity and wit. This is a privileged look at the band before they became adults with families, retiring to the studio to record what is often considered their masterpiece: Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Documentaries on the Beatles range from Albert and David Maysles The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit (1964, re-edited in 1991), to an engaging look at the woman who headed the Beatles Fan Club in the early years, Good Ol’ Freda (2013). Nothing has come along that is close to director Ron Howard’s evocation of the heady, barnstorming days when The Beatles became the most famous musicians in the world. Howard (who has his own pop culture credentials from The Andy Griffith Show, Happy Days, and as an Academy Award-winning director), conducts interviews with the remaining members, Paul McCartney and Starr. They are relaxed and honest as any two guys talking about a band they once had. “Four votes had to be carried for an idea to go through,” explains McCartney, “we were a four-headed monster.” Together with archival interviews with George Harrison and John Lennon, we hear what it was like to be caught in the maelstrom.

They were a band of brothers with more than a touch of the Marx Brothers in the mix. We’re familiar with Lennon’s head-spinning press conference quips. Like naughty schoolboys, they had great fun with the media madness until it began to be too much of a good thing. Film director Richard Curtis observes that “the Beatles were a kind of dream of how you might go through life with your friends.” He later notes that “they had a real lack of self pity.” When not in the limelight they were always composing. McCartney, left handed, and Lennon, right handed, would sit together — brilliant twins exchanging ideas. They would contribute riffs and lyrics, developing new songs in tandem, to the point that they often couldn’t remember who had written what. “We’d sit opposite and start and ricochet off each other,” recalls McCartney. If you listen carefully, you’ll even hear Lennon in a hotel room playing on a melodica what years later would become the intro to “Strawberry Fields.”

The clips from their concerts are extraordinary (many rare Beatles performances have surfaced lately in social media). But the on-line footage is paltry seconds compared to the film’s digitally enhanced sound, remarkable color correction, and numerous rare live performances from around the world. There are beautiful extended shots of each Beatle and the re-mixed vocals are clear and singular. Each voice is distinct: McCartney’s great rock yelps and Lennon and Harrison’s slight Liverpool reediness. Their harmonies are always in tune, the result of years of working together despite the primitive sound systems and a lack of sufficient monitors. McCartney’s booming Hofner bass sets the groundwork for every song. Harrison was the master soloist, his guitar hooks adding color to Lennon’s rock and roll rhythm guitar. The later’s sardonic humor can be gleaned from the smirk he often sports on stage. Playing at Shea Stadium on the “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” finale, he solos on electric piano with his elbow and breaks into hysterics along with Harrison.

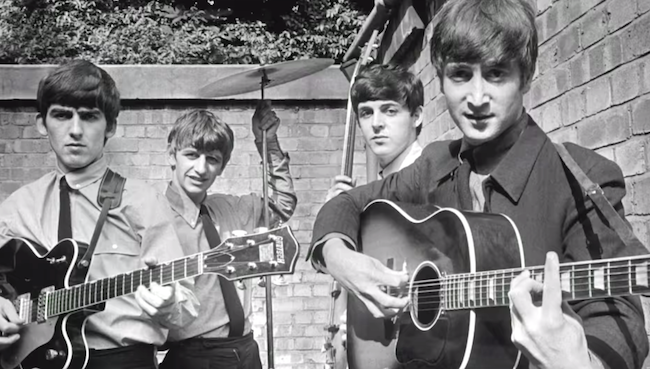

A scene from “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years.”

And Ringo will no longer be under-appreciated. McCartney says that when Ringo sat to play with them in 1962, they all said ‘yeah, that’s it.’ The band was complete. In addition to being rock solid, declares McCartney, Ringo was “cheeky,” which was a quality that suited the band well. In the live performances his snare drum is mixed so that we feel the power of his playing. He holds everything together with implacable self-assurance as well as a poetic sense of where to place the backbeat. Left-handed, Ringo plays his cymbal with a strong right hand, a rare trick for a young drummer. In many early songs (“Another Girl” and “Help,” for example), the tempo falls somewhere between a straight eighth-note rock feel and a swing or shuffle. Ringo parses the difference, giving the early music great tension and forward motion. He tells us that in the stadium shows the screaming was so loud he couldn’t hear a thing and that he had to play by rote and by watching the guitarist’s hands. The beat never wavers.

There are a judicious number of interviews from non-Beatles; subjects make statements and the film moves back to the shows. Elvis Costello and Eddie Izzard speak briefly. Sigourney Weaver talks about attending an early gig (I believe we catch a glimpse of her in a crowd). Malcolm Gladwell talks about the “muscle flexing of a new generation.” Richard Lester, who directed the group’s films, makes a few statements about trying to catch the band’s spirit on celluloid. Larry Kane, a journalist and newscaster in Philadelphia, asked the group’s manager, Brian Epstein, if he could do an interview and wound up the only reporter to travel on the entire tour. He had no idea it would be a high point of his reporting career. Perhaps his straight-laced professionalism appealed to Epstein, who McCartney explains “was classy.” He put them in suits, told them to bow, and brought it all together. The fifth Beatle would have to be producer George Martin, who had previously recorded the Goon Squad, which featured Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan. He knew humor, he knew music, he was dignified and patient and knew when to step in and “he knew to leave us alone.” McCartney says “On the early records George Martin was a god.”

Not Elvis, Sinatra, nor any other popular phenomenon since can really compare to what we see catch glimpses of here. The spontaneous frenzy, along with the “sheer volume of invention,” probably has no equal. But touring eventually became “a freak show” and the band members wanted to make music, not be players in a traveling circus. The song “Help” was written by Lennon in response to the chaos; the movie gives us the entire song played live. The 1965 album Rubber Soul was a big leap, reflecting that records were growing more sophisticated and experimental. It was time to move on. We know there were masterpieces to come. This boisterous chapter of the Beatles phenomenon ends with the final resonating chord from the end of “A Day in the Life,” the Sgt. Peppers album cover appearing on screen. The finale is grand and it lingers in the mind; a fit ending to a marvelous film.

Though The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years will be available on Hulu, I recommend seeing it in a theater. As a bonus, film screenings will include 30 minutes of bonus concert footage from The Beatles 1965 Shea Stadium performance.

Footnote: In the Arts Fuse several years ago, I wrote about my own experience being in the studio audience for the Beatles premier appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show: Hey, You Kids Want Tickets to See the Beatles?

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: documentary, George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Ron Howard, The Beatles