Fuse Book Review: Novelist Jay McInerney — Nimble Chronicler of America’s Upper Class

Jay McInerney’s characters may live on exotic mixed drinks and fine wines, but for all of that they suffer moral dilemmas and have consciences they cannot silence.

Bright, Precious Days, by Jay McInerney. Knopf. New York, $27.95.

by Thomas Filbin

You know who they are: the upper class, the shakers and movers, the ones who run things. They attend notable prep schools, then the Ivies or Little Ivies, and go onto marry classmates or classmates’ siblings, their wedding announcements in the New York Times. Eventually they take their preordained places in finance, publishing, government, and philanthropy. They seem to negotiate life effortlessly, free of forces like gravity or bad luck that dog the rest of us. Not all of them are fabulously wealthy, but when they need to escape life’s stresses they somehow always have a relative with an available house on the Vineyard or the Hamptons. These are the people who inhabit the novels of Jay McInerney; his signature ability is to penetrate their façade of certainty, revealing the angst, addictions, and guilt that lie under polished and placid surfaces.

Russell and Corinne Calloway are the subjects of Bright, Precious Days, as they had been in McInerney’s earlier novels Brightness Falls and The Good Life. Now middle aged, they are raising eleven year old twins, Jeremy and Storey, live in a crumbling rented loft in lower Manhattan, and are about to be roughed up by a midlife crisis or three. Russell runs an old and respected New York publishing house which specializes in literary fiction. His latest find is Jack Carson, a redneck genius whose semi-literate stories are critically acclaimed. Having tasted success with Jack’s first novel, Russell is seduced by the possibility of publishing another blockbuster title. He hands over a huge advance — larger than the little house has ever coughed up before — to a novelist-journalist who has written a harrowing account of his capture by Islamic fighters in Waziristan. It is early 2009 and all the world is making truckloads of money so, Russell asks himself, why not him? Why not swing for the fences this once instead of publishing a list filled with quiet, mid-list books?

At home, Russell is a bit of a pretentious gourmand and oenophile; “He belonged to a new breed of male epicureans who viewed cooking as a competitive sport, and pursued it with the same avidity that others had for fly-fishing or golf, with the attendant fetishization of the associated gadgetry and equipment.”

Urbanites consume with frenzy, and McInerney uses an ’80s fiction device of mentioning, whenever possible, brand names: Prada, Gucci, Chanel, and Ralph Lauren. The technique has been criticized as being more about the worship of the materialistic than a satire of product placement. Still, the strategy succeeds in showing how imprisoning consumption becomes when it is inescapable, as omnipresent as the air you breathe. Corinne, who had formerly worked on Wall Street and now runs a feed-the-hungry charity, is contemplating resuming an affair with a financial tycoon she was briefly involved with after September 11. Russell has had his own past indiscretions unknown to his wife but, as we eventually learn, he weighs the sin of infidelity differently depending on whether the husband or wife is the perpetrator.

The Calloways lead a very social existence; dinners out, benefits, gallery openings, and ‘special’ events are routine for people like them, a class that represents the cultural vanguard. When Russell and Corinne dress to attend a benefit, their children whine that they are go out too much. Corinne defends herself by insisting that these events are often dedicated to helping good causes.

“Why don’t you just give the money and stay at home?” her son asks.

“Because adults like parties,” her daughter interjects.

While all this high-toned merry making is going on, the financial crisis explodes, taking down everyone in their circle: people who work for Lehman Brothers, the over mortgaged, and others who, up to their necks in debt, can’t make their margin calls once the make believe bubble of prosperity bursts.

Russell’s publishing house is imperiled when the Waziristan story is challenged on social media; the writer, it is claimed, was really holed up in Lahore for nine weeks with drug dealers, then decided to make the most of it since he was reported as being abducted by soldiers in the press.

After the market collapses and marital betrayal is discovered, Russell and Corinne are left to decide whether to split or to dredge up the inner resources of character and determination that have long been submerged in the getting and the spending.

This is, if nothing else, a New York novel. McInerney’s keen eye surveys the nuances of style and tone that Gotham sophisticates customarily display. When Russell takes someone to lunch, he chooses a trendy West Village place, “…the Fatted Calf, a self-proclaimed gastro-pub inspired by recent trends in ever-trendy London. Although it has been open less than two years, it looked as if it had been in business since Prohibition, with creaky mismatched tables and chairs, its framed butcher’s eye diagrams of vivisected cow carcasses, on which each cut was carefully labeled. The maître d’ – if a guy with a chullo cap and a soul patch qualified as such – led them to a rickety back table with a rough, water-stained top.”

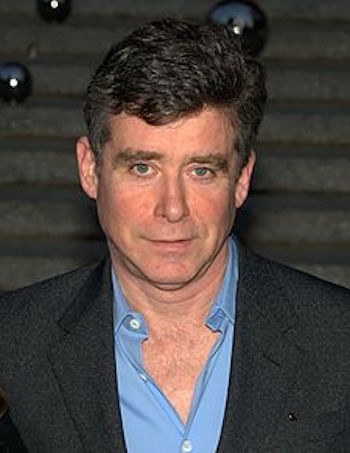

Author Jay McInerney. Photo: Wiki Common.

From the farmer’s market at Union Square to the trendy eateries in the meat packing district, Bright, Precious Days knows its backdrop and creates a world of tension and excitement that leads us to understand why people who live in Manhattan are so obsessively energetic and loyal. Despite their complaints, they could no more leave the city than polar bears move to Miami. New York isn’t where they are, it is what they are.

McInerney writes beautifully about dreams, ideals, and the inner life. His prose has a psychological adroitness that exposes a character’s emotional life without making his or her feelings an excuse for authorial sentimentality. His people may live on exotic mixed drinks and fine wines, but for all of that they suffer moral dilemmas and have consciences they cannot silence.

Critics either idolize McInerney as the new Fitzgerald or revile him as an aging brat packer, possessed of little more than a flashy style. He came to prominence at an early age with Bright Lights, Big City in 1984, and that notorious success continues to provoke envy and mockery in equal parts. Four times married himself, McInerney knows a thing or two about torturous relations between men and women, even though — in the end — his couples look and behave like updated versions of their 1950s parents. One of his ex-wives, Merry McInerney, wrote a novel, Burning Down the House, which portrays a McInerney-like character as a pompous, sycophantic bore. Ouch.

His New York is the devil’s playground: all the deadly sins — with the exception of sloth — are on display. Who in their right mind would choose to be lazy in the pursuit of fame and money when it seems to be there for such easy taking? Pride, greed, envy, lust, anger, and gluttony all do quite well in McInerney’s oh-so-pricey Manhattan.

If you like stories of sin and redemption in a pampered secular world, Bright, Precious Days is one you will relish — though be warned, you will have to scale mountains of Prada.

Thomas Filbin is a book critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and The Hudson Review.

Tagged: American fiction, Bright, Jay McInerney, New York City, Precious Days, knopf