Fuse Film Review: “The Witness” — A Brother’s Search to Expose the Myths of Kitty Genovese’s Murder

The quest for answers about Kitty Genovese’s murder is really just a red herring for a much more personal journey: the quest of a brother to understand his sister as a person, not just as a metaphor for complacent inaction.

The Witness directed by James Solomon. At the Regent Theatre, Arlington, MA, Aug 26 through Sept 1.

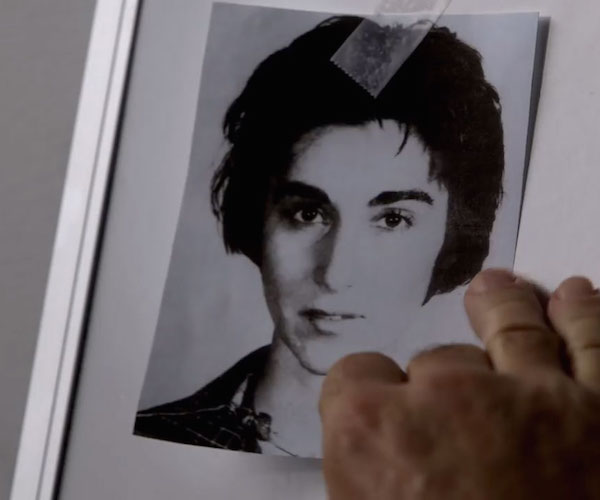

A scene from “The Witness.”

By Neil Giordano

The name “Kitty Genovese” has become one of the synecdoches of late twentieth century American urban folklore, the perfect image of a cold-hearted concrete jungle where a helpless young woman was left to be murdered by her callous neighbors. For years a trope of pop sociology, the eponymous murder of 1964, in Kew Gardens, Queens, has since been re-analyzed and the facts disputed. Still her name continues to provoke deep-seated feelings, fears of helplessness amid an indifferent crowd. The new documentary The Witness turns the story inside out once again, revisiting the facts and the fables through the deeply personal narrative of Genovese’s younger brother Bill and his obsessive search for the truth.

The film begins as a quest by Bill Genovese to debunk many of the long-held assumptions about both the circumstances of the murder and the neighbors’ reactions. Fifty years after the killing, he systematically tracks down key witnesses, as well as journalists and lawyers, who reveal a much more complex picture of the night in question than what was reported at the time — who saw and heard what, what the police did or maybe didn’t do, how the story was told in the media in the days and months afterward. In the process, he casts plenty of doubt on the infamously reported “fact” of the uncaring bystanders. Still, Genovese is no forensic specialist, and much of what he finds ends up raising issues about the inevitably fragile nature of memory. How reliable are the five decade old testimonies of now-elderly witnesses? What is probably the most damning here is the indictment of the New York Times and its reputation for accurate reporting. The paper’s seemingly ‘factual’ account created an enormous number of myths.

But the quest for answers about Kitty Genovese’s murder, while enlightening in The Witness‘ exposition, is really just a red herring for a much more personal journey: the quest of a brother to understand his sister as a person, not just as a sociological phenomenon or a metaphor for complacent inaction.

Here the film creates an involving portrait of a young woman who struck out on her own in mid-century America. It unearths details that were not made public at the time of the murder and have been overlooked ever since. Through old home movies and stills — as well as recollections from her acquaintances — Kitty Genovese springs to life. She was a popular yet idiosyncratic young woman; voted class clown in high school, she attracted a variety of admirers and friends. Kitty was also a woman who carved out her own path in life, choosing to stay in the city when white flight during the 1950s prodded her family to depart Brooklyn for the comfier confines of suburban Connecticut. To reveal more would be to spoil the experience of the film, but the details about Kitty’s life and her time in New York City during the early 1960s individualize the woman in the famous photograph that’s featured on the movie’s poster (we learn that the photo’s backstory is symbolic of Kitty’s life as she chose to live it).

As The Witness reaches its final act, the story begins to sputter when the focus shifts to Bill himself. He is obviously spinning in an epistemological cul-de-sac, obsessed with the search even though he is awkwardly implored by his other siblings and immediate family members to stop. He even tries to interview Kitty’s murderer, still in prison after being swiftly caught and convicted in the months after the crime. Instead, he settles for a quite astonishing sit-down with the murderer’s son.

Bill will not quit investigating, and we learn that his search is driven in part by his own choices in life, choices he’d made directly as a result of his sister’s death. The myth of the neighbors’ inaction had a profound effect on him as a teenager (he was sixteen when she was murdered). His view of the world was shaped (tragically limited) by the metaphors of vulnerability invoked by her name. The Witness becomes his reckoning with that truth in hindsight.

Credit must be given to the director James Solomon, who also wrote the guiding narration, for weaving together such a contradictory amalgam of documentary genres and narrative pathways. At some point, Bill Genovese must have realized that he didn’t know how to put all of his discoveries about Kitty and himself together — at the root of the confusion lies his paralyzing uncertainty about what to do with such a personal story. The final sequences of the film are discomfiting to watch: most of us will most likely side with relatives’ requests that Bill end his search. But the film would not be what it is without these embarrassingly painful moments. Heartbreaking and gloomy, The Witness ultimately grants us intimations of redemption, private and as well as social.

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

Tagged: documentary, James Solomon, Kitty Genovese, Neil Giordano, Regent Theatre