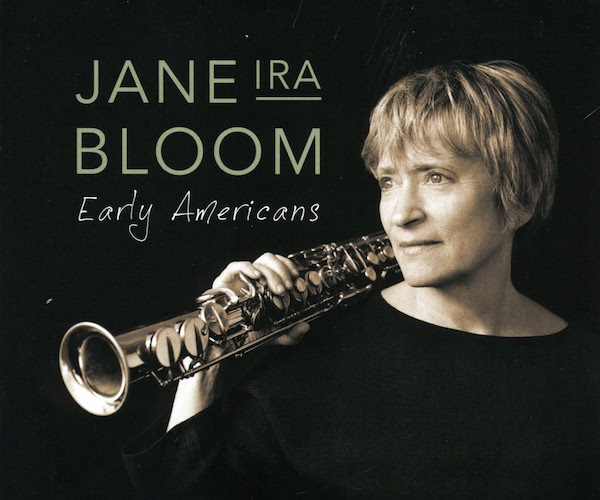

Jazz Performance and CD Review / Commentary: Jane Ira Bloom’s “Wild Lines” and “Early Americans”

Exposing the jazz impulses in Emily Dickinson’s poetry is not an agenda for the novice.

Bloom says this about the title: “There’s a primal gut feeling, about the rhythm, about getting to the core of the music, the roots at the heart of it. And of course, we’re playing American music.”

By Steve Elman

Why take the risk?

Let’s say you’re an accomplished and acclaimed saxophonist – although (of course) you’re not compensated in any way proportional to your talent and achievements. You have a significant body of work. You’ve chosen particular paths of technique, improvisation, and composition – they’re defined paths, but they’re wide enough to provide you with challenges and satisfactions for the rest of your life. Why stretch yourself?

I apologize for trying a reader’s patience, but I have to take the long way around to come to some answers to that question.

Jane Ira Bloom is the saxophonist I’m talking about. She decided early in her career, when she was still living in Boston, to concentrate on the soprano saxophone, and she’s now at the top of her game as player, improviser, song interpreter, and composer.

I’ve already written at length about Bloom the technician and Bloom the song interpreter. But a new project, which she premiered April 28 at Bezanson Hall on the UMass Amherst campus, puts her compositions in the spotlight, and represents just the kind of risk I’m talking about: it’s her first adventure into combining spoken word and music.

I spoke with her about the project recently, when she described the Amherst gig (too disparagingly, I think) as “really just the first run-through.” There are two more performances coming this fall which will give listeners in New York and the DC area the chance to hear it in a more polished form.

The suite, called “Wild Lines,” sets a series of texts by Emily Dickinson within the frame of Bloom’s original compositions, played by her working band. The concept may sound simple, but it is mightily ambitious.

Bloom remembers seeing Julie Harris in the television version of The Belle of Amherst, the one-actress play by William Luce. She says:

[Harris] had an irreverent quality in her portrayal of Dickinson [that appealed to me].I guess the seed was planted then. [Dickinson is] wild, funny, sardonic, brilliant. Parts of her poetry would just knock me out. Some fragments would keep me thinking all day long. In a way, it was a jazz-like communication. There’s something improvisational about her work, why I thought her thoughts and words were so compelling, words [strung] together like pearls.

She WAS a musician, you know, and an improviser. She used to go upstairs in the evenings and make up songs on the piano. That improvisational quality in her musical experience is also in her poetic experience.

Exposing the jazz impulses in Emily Dickinson’s poetry is not an agenda for the novice. To be sure, there are some Dickinson texts with music right there on their surfaces. “One note from / One Bird / Is better than / a Million Word[s]” is sure-fire. “A Murmur in the Trees – to note – / Not loud enough – for Wind – ” is a challenge for a musician, but at least sound is suggested.

But what to do with this: “I felt a Cleaving in my Mind – / As if my Brain had split – / I tried to match it – Seam by Seam – / But could not make them fit.”? Or this: “How many Flowers fail in [the] Wood – / Or perish from the Hill – / Without the privilege to know / That they are Beautiful”? How do you make these texts musical? How do you build a lattice for enigmas and ambiguities?

Jane Ira Bloom in action. Photo: Susan Cook.

And then there are all those practical questions standing between the concept and the reality. How many texts are too many? What kind of speaker can do justice to those words? Should the speaker “impersonate” Dickinson or just serve as her dramatic voice? How should Bloom balance the volume of the music against that of the texts so that the audience will hear meaning and not just sounds? Should the music directly reflect the texts or should the relationship be intuitive?

Plus the big question, the one that confronts every artist taking the risk to do something new: who will buy it?

It is to her credit that Bloom understood all these concerns and went forward anyway, getting a “New Works” grant from Chamber Music America that allowed her to hire actress Deborah Rush as speaker and Seattle native Dawn Clement as pianist, with long-time colleagues Mark Helias on bass and Bobby Previte on drums and small percussion. These four distinctive talents gave her the tools she needed to create something new for her and something new for Dickinson – a conversation across generations.

She says,

I wanted to help reveal [Dickinson’s work] in the way that it revealed itself to me as a jazz musician. I wanted to put in a context where the music would let it speak in its mindfulness, not to underscore the poetry, but to allow the two to mingle.

Although the Amherst performance didn’t fully realize that vision, enough went right so that anyone listening could hear that “Wild Lines” was a special work in progress.

Bloom said, “There was a lot of sturm and drang” during the sound check, so there wasn’t optimal balance between amplified voice and unamplified instruments. The texts were not provided in the program, which impeded listeners’ ability to engage with the words. There also was a serious snafu with Rush’s cordless mic during the performance that obscured the words of one of the most important poem settings. Since there was no funding for a set, the “staging” had to consist of a makeshift window framed by lace curtains, a little table with a hurricane lamp, and a chair on a scatter rug, with Rush in a long retro dress.

When I asked Bloom how the first performance measured up to her expectations, she pointed to the aspect that most dissatisfied her: the transitions between the individual text settings. Sometimes there was too much space between the pieces, allowing attention and energy to slip away; sometimes a segue was too abrupt, asking listeners to adjust their ears too quickly. This is not just an issue for her; it is one of the prime challenges facing the composer of any suite or multi-part composition. The composer wants individual elements to be effective, but she knows that her suite will fall apart without a sense of overall motion. For maximum effect, the spaces are crucial.

Even with the first-performance flaws, it’s clear that “Wild Lines” is already on its way to achieving this goal: the first piece (meditative, with the same name as the suite itself) and the last (“Big Bill,” exuberant and celebratory) are both instrumentals, creating a pleasing frame. The text settings begin with “Emily and her Atoms,” with Bloom improvising into the belly of the piano and Rush reciting “Excuse / Emily and / her Atoms / The North / Star is / of small / fabric / but it / implies much / presides / yet.” This tentative tone gradually gives way to stronger statements, concluding with a boppish, life-affirming “Bright Wednesday,” featuring these lines: “I don’t like Paradise – / Because it’s Sunday all the time – / And Recess – never comes – / And Eden’ll be so lonesome / Bright Wednesday Afternoons – ”

Bobby Previte, Bloom’s percussion alter ego. Photo: Eyeshotjazz.com.

Some of the transitions were just right — for example, the drum solo between the sixth and seventh pieces, “A Star Not Far Enough,” and “Singing the Triangle.” “Star” is a setting for part of “A Murmur in the Trees” (quoted above). “Triangle” frames words from a letter in which Dickinson describes the inspiration she got from a circus parade in Amherst (“Friday I tasted life. It was a vast morsel”). Getting from one to the other would challenge even the best drummer. “Star” has a lyrical theme, with Bloom and Rush accompanied by piano and bass only; Clement added color to Bloom’s work with some inside-the-box percussion and then held some of her strings open so that Bloom’s powerful sax playing could pull resonances out of the piano. The drum solo by Previte that came immediately after built on the subtle forward motion in “Star,” transformed it into something suggesting the arrival of a circus, and segued directly into “Triangle,” a bright line with a catchy six-note motif. Bloom must have been pleased with how well that transition worked.

In fact, Bloom’s special rapport with Bobby Previte is crucial to the realization of “Wild Lines.” She says, “We GET each other, both energetically and with the spontaneity to develop one moment and move to the next one. We’re [both] compositional improvisers and improvisational composers.”

She was equally insightful in describing her other collaborators. Pianist Dawn Clement, who also has credentials as a singer, provides Bloom with a “connection to breath [that] allows her to accompany in a different way. She has a natural rhythm that’s both spacious and compelling.” Bassist Mark Helias has “an amazing sonic intellect. His rhythmic choices, creative choices – nothing ever seems the same. He’s composing orchestrally even as he plays with a [conventional] feel.”

From the time she conceived the project, Bloom wanted the Dickinson texts to be read by the distinguished actress Deborah Rush, a long-time friend who was a regular on Strangers with Candy and recently played roles in The Good Wife, Girls, Orange Is the New Black, and Inside Amy Schumer.

Bloom says,

Great actors — it’s still magical for me the way they find insight and humanity in everything. Deborah’s got something – [the text] goes inside her and comes out transformed. I wonder, ‘How does she do that, make [the words] jump off the page like that?’

These observations start to answer the question I began with: Why take the risk? The simplest reply is that Bloom loves building connections through music, and this idea allowed her to work with an actress she admires and players with whom she has special rapport.

Another answer: this is the latest of her self-challenges and interactions other media, encounters she uses to put new depth into her improvising and writing. Early in her career, she used dance to develop a distinctively physical style of playing and a signature technique, passing the bell of the saxophone across the mic to create phasing effects that she calls “Doppler swirls.” Another example – also one supported by Chamber Music America – was a suite inspired by Jackson Pollock’s painting, recorded on her CD Chasing Paint (Arabesque, 2003).

There is a third answer to the question that goes to the heart of art. Each human being has a need to make things special, a need to shine a light on the things he or she values most. It’s a need that the cultural anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake sees as the wellspring of all the arts. For the artist to fulfill that need, to scratch that ever-present itch, she must take risks and hope that she can bring others along with her. The extraordinary consistency of Jane Ira Bloom’s work is what makes risks like “Wild Lines” so satisfying for the rest of us.

But who will buy?

Glenn Siegel’s Magic Triangle concert series, resident at the Fine Arts Center of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, took the first step, and kudos to him and his production team for paving the way. Two more performances of “Wild Lines” are set for the fall; Bloom is eager to come to Boston as well, if only one of our august institutions would take a little risk for a big reward. Her group (with another long-time collaborator, Kent McLagen, replacing Helias on bass) will perform the work on Friday, October 14 at 7 p.m and 9 p.m. at the KC Jazz Club in the Kennedy Center for the Arts in Washington DC. Six days later, they will do it again, on October 20, at the Bruno Walter Auditorium in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

Bassist Mark Helias. His big sound is the heart of Bloom’s band. Photo: Robert Burke.

Those are pretty strong venue credentials. Would it be so big a stretch for the New England Conservatory to bring Bloom to Jordan Hall, or for the ICA to commission a performance in their beautiful concert space overlooking the harbor, or for the Gardner Museum, or Berklee, or Boston University, or Harvard, or MIT, or CrashArts / World Music, to bring Bloom back to her home town for music that very much deserves to be heard?

Bloom says she hopes to record the suite eventually, but that will not have the same impact as live performance. No CD can provide the third dimension that comes to listeners in a performance space, and this work has an element of acting that not even a DVD could capture effectively. Who will buy?

If all this has whetted your appetite, you can enjoy a taste of “Wild Lines” right now; some of the music is already available on Bloom’s outstanding new recording Early Americans (Outline, 2016). The CD is not a “Wild Lines” afterthought; it might better be called a forethought, because it includes seven pieces that she adapted for the Dickinson suite, plus five more striking originals and a stunning solo performance of Leonard Bernstein’s “Somewhere.” Bloom says that the two projects “have different lives,” but those two lives are of equal significance. Early Americans is Bloom’s first full recording of tunes with just bass and drums, and the concept is realized superbly. Mark Helias and Bobby Previte are her collaborators here once again. They and Bloom have never sounded better, thanks to Jim Anderson’s beautiful engineering. Just click over to Spotify, listen to “Big Bill” or “Singing the Triangle,” and tell me you wouldn’t like to hear a lot more from the same people.

More:

The three players who accompanied Bloom in “Wild Lines,” including pianist Dawn Clement, can be heard performing with her on Bloom’s CD Wingwalker (Outline, 2010), which is also hearable via Spotify.

I would be remiss if I did not mention Bloom’s husband, the veteran New York actor / director Joe Grifasi, who provided the dramatic framework for “Wild Lines,” and presumably will have a little more in the way of set to work with in subsequent performances.

The Magic Triangle series, which almost never gets attention in the Boston press, is a venerable institution for creative improvisation in central Massachusetts, and its forthcoming season shows admirable taste, including performances by Wadada Leo Smith and Vijay Iyer, Oliver Lake, Anthony Davis, Mary Halvorson, and Tomas Fujiwara. Here’s the full rundown.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: "Wild Lines", Chamber Music America, Chasing Paint, Dawn Clement, Deborah Rush, Early Americans, Emily Dickinson, Glenn Siegel’s Magic Triangle

Steve poses a challenge to Boston’s music venues in this commentary. “Wild Lines” is set for October performances in New York and Washington D.C. But none in this area. The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, New England Conservatory, Rockport Music, Berklee College of Music, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum or one of the other performance spaces in Boston. Shouldn’t somebody make it possible for Bloom to perform her exciting new piece in Boston. Anyone out there who can help?

I would (and I know Kent McClagen personally) if I had the funds as I already produce on a grassroots, independent and “non-profit” basis (not an organization, ticket sales) in Cambridge since 1/2015. The next two at the Lily Pad 8/18/16 and 10/11/16, world-class musicians from NY and Chicago. About time a Boston writer, thank you, acknowledges how Boston fails and is so provincial when it comes creative improv music esp from the Jazz angle. Very little of the media also responds poorly. Thanks Bill for seeing the light and stating the obvious. I’m Alex collecting tics at the Lily.