Classical CD Reviews: Houston Symphony Orchestra plays Dvořák and Goerne and Eschenbach perform Brahms

Do we really need another recording of Dvořák’s last four symphonies? And an album of Brahms lieder from two musicians in their prime: Christoph Eschenbach and Matthias Goerne.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Do we really need another recording of Dvořák’s last four symphonies? Has a question like that ever stopped an orchestra from making such a set? Those were two questions that popped into my head while listening to the first pair of installments of Dvořák’s “Final Four” (Symphonies nos. 6-8) made by the Houston Symphony (HSO) and its charismatic new music director, Andres Orozco-Estrada.

The answer to both of the above queries is, of course, no. And it’s something of a pity here, not because these aren’t well-played performances – they are – but because this music really doesn’t require this kind of advocacy: it would be much better spent on the first five Dvořák symphonies, say, rather than the last four, which are already overrepresented in the catalogue.

Oh well. Perhaps if these discs are well-enough received they can pave the way for a complete Dvořák cycle.

And they should go over well because the HSO’s musicianship is of a very high caliber. That shouldn’t be a surprise: this is an orchestra with an excellent pedigree (it’s been led over the years by the likes of Ferenc Fricsay, Leopold Stokowski, Andre Previn, Christoph Eschenbach, and Hans Graf), even if it hasn’t been widely recorded of late. Thankfully, that last trend seems to be over.

To these ears, the best performance of these three symphonies belongs to the Sixth. It’s on the faster side (which helps once the somewhat-long-winded finale rolls around), full of color, and the orchestra’s playing consistently packs a welcome jolt of energy. The winds and brass are particularly notable throughout: listening to the full but slightly brash articulation of the horn rhythms at the start of the first movement is but a premonition of some of the riches to come. Orozco-Estrada and his orchestra clearly have the rustic pulse of this music in their bones and their playing is, commensurately, full of life. It’s a reading, too, that drinks deeply from the well of Dvorakian lyricism: not only the mellifluous slow movement but also the fast outer ones and the driving third-movement Furiant sing with convincing passion.

Much the same can be said for the HSO’s account of slightly-more-familiar Seventh Symphony. This is a reading marked by an impressive attention to the score’s many details: its terraced dynamics, numerous articulations, and layers of counterpoint are each clearly delineated. As a result, you can hear almost everything Dvořák wrote into the piece and much of it – like the many woodwind fillips and different voicings of the string textures – stand out with impressive clarity.

Interpretively, Orozco-Estrada seems to be most at home in the Seventh’s last two movements. The HSO’s reading of the Symphony’s Scherzo is vitally rhythmic – truly one of the great accounts captured on disc – and the finale builds with inexorable momentum. That said, the more spacious tempo conductor and orchestra take in the first movement robs it of some of its frenzied character and the lovely second sounds rather emotionally detached.

Their reading of the Eighth, too, offers some flexibility of tempo. In the opening movement, the slower pace works very nicely in the introduction – it’s almost as though the music depicts the start of a day in the country – and fits with the recollection of this music later in the movement. But in the finale, especially over the long stretch for strings and winds before the coda, the music requires more momentum: the HSO plays with sumptuous tonal refinement but there’s no escaping the feeling that something is missing.

Still, the middle movements fare well. There’s incandescent drama in the second – the huge first climax gives way to playing of breathtaking stillness, almost on a dime – and the third, while it’s a bit luxurious for my tastes, has a charming lilt to it.

Solos abound in these symphonies, particularly the Eighth, and they’re all handled with grace and color, led by principal flute Aralee Dorough and concertmaster Frank Huang (who’s since absconded Houston to take over the first chair of the New York Philharmonic). The HSO’s brass – especially the horns – are terrific. To hear the latter drilling their trills in the Eighth, for instance, is to revel in some of the most raucous, confident horn playing out there.

So, while these discs don’t replace the classic accounts of these symphonies by Kertész, Kubelik, or Dohnányi, they at least complement the competition respectably. And they have the salutary benefit – along with recent releases from the Dallas and Fort Worth Symphonies – of reminding us that there’s more, sometimes much more, to Texas than just cowboy boots and Ted Cruz.

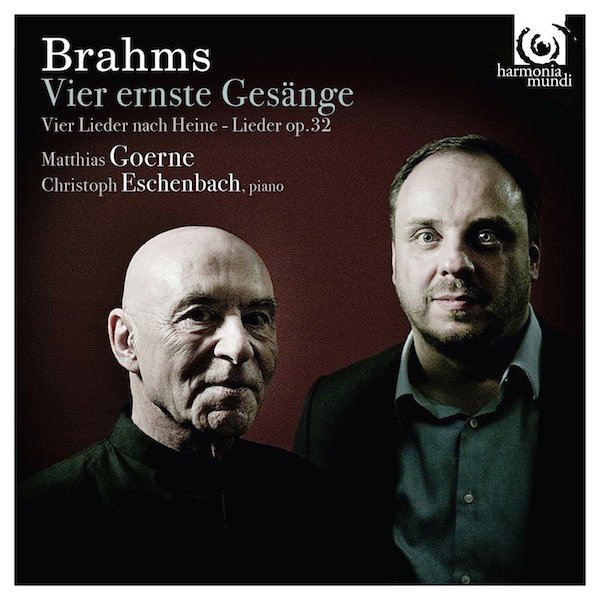

The ups and downs of Christoph Eschenbach’s post-Houston conducting career (he stepped down as music director there in 2001) have been well documented but the fact remains that he is an excellent pianist and a compelling interpreter of Romantic repertoire. His new recording of Brahms lieder with Matthias Goerne for Harmonia mundi demonstrates this exceptionally well.

The focus of the disc is a performance of the Vier ernste Gesänge, Brahms’s late (1896) setting of biblical and Apocryphal texts focusing on death. For such songs, you could hardly ask for a better singer than Goerne, whose rich, velvety tone; thoughtful musicianship; and deep, emotional understanding of the texts is ideally suited to this music.

There’s resigned acceptance in his singing of the first three songs with their melancholy verses from Ecclesiastes and Sirach’s Ecclesiasticus, but no bitterness: we all die, after all. This is the way things are, and we need to accept that we can’t change that fact. At least the final song, “Though I speak with the tongues of men and angels,” offers something by way of a moral – love one another – and a measure of consolation.

Such messages have hardly sounded so beautiful or heartfelt as they do here. Goerne sings each of these songs with such purity of focus, musical intelligence, and delicacy of tone that one can hardly not be moved by them. Indeed, to hear him singing in his upper register over the last two (“O Tod” and “Wenn ich mit Menschen- und mit Engelszungen redete”) it to experience some of the most ravishingly beautiful singing this artist has yet committed to disc.

Eschenbach matches the seeming effortlessness of Goerne’s performance with playing of striking rhythmic and textural clarity. It’s apparent that he identifies closely with these lieder, so well-voiced is his account the keyboard part and focused his phrasing. Technically and interpretively, he’s also perfectly at home in each of them, powerfully mining the stern refrain of the first, finding the rays of light that shine through (especially towards the end) of the second, working a magical transition into the second half of the third, and energetically balancing the martial and introspective sections of the last.

These same characteristics are evident across the album’s other selections, which include the nine Lieder und Gesänge, op. 32, and five settings of poems by Heinrich Heine (two from the op. 85 set, and three from op. 96). The Heine’s offer a nice bridge to op. 121 and the earlier Lieder offer a view of Brahms as more of a traditional Romantic song composer (the texts focus primarily on love and longing). Indeed, the only real complaint I have is that the all of opp. 85 and 96 weren’t included on this disc, so captivating are these performances. But what we do have here is striking and powerful from two musicians who, in many ways, are in their prime.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette

Tagged: Andres Orozco-Estrada, Brahams, Christoph Eschenbach, Dvořák, Harmonia Mundi, Houston Symphony, Matthias Goerne