Music Interview: Debo Band — Another Side of Ethio-Groove

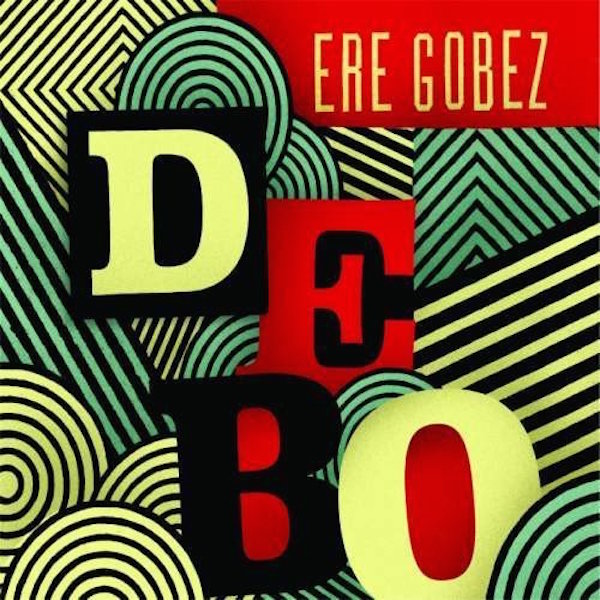

Boston’s Debo Band expand their heterophonnic horizons on Ere Gobez.

By Noah Schaffer

Boston’s 10-piece Debo Band began developing its distinctive brand of crowd-pleasing fun while playing at Jamaica Plain house parties and bowling alleys a decade ago. Now have the group has released its first album in four years, the bright and booming Ere Gobez, which adds psychedelic rock and innovative rhythms to their Ethiopian-inspired sound. They celebrate the record’s release with a concert at Cambridge’s The Sinclair (in association with World Music/Crash Arts) on Thursday night. The equally exuberant outfit, Providence’s What Cheer? Brigade, will be the opening act.

Recently the Arts Fuse talked to Debo Band’s Harvard-educated ethnomusicologist, band leader, and saxophonist Danny Mekonnen about the evolution of the band’s sound and the variety of styles on the new album.

Arts Fuse: How has the band’s sound changed since it formed a decade ago?

Danny Mekonnen: At the beginning I think we were more of a repertoire band. At the time it was the sound of [1970’s Ethiopian outfits] the Imperial Bodyguard Band and the Haile Selassie 1 Theatre Orchestra. I’d seen pictures of the Selassie orchestra: there were 20 handsomely clad men in tuxedos and the instruments included saxophone, trombone, trumpet, accordion, strings, and an upright bass. On the recordings I could hardly make everything out but I could tell there was a lot going on. The cacophony was really interesting to me and primarily acoustic — it was heterophonic.

AF: Can you explain that term?

Mekonnen: Heterophony is when a bunch of people are playing same melody but a little differently, as opposed to New Orleans polyphony where multiple lines are happening and everyone is improvising. Heterophony is an element of Ethiopian music but it’s not exclusive to it — it’’s used elsewhere in Middle Eastern music as well. At first we were trying to get as close to that traditional sound as possible. We did that for the first three years, but didn’t want to become beholden to that approach. To break free, we’d take funky late ’70s tracks from artists like Mahmoud Ahmed and try to deconstruct them. So instead of the original brass section we’d have two tenor saxophones, guitar, bass, and drums — we’d try to rearrange the orchestral sound of that music. And I think that orchestral element became ingrained in the group.

We were especially listening a lot to [recently deceased Ethiopian saxophonist] Gétatchèw Mèkurya. Once we got the fundamentals down, we began to feel more free. Still, when we recorded our first LP we were just beginning to transition away from being a repertoire band that played faithfully transcribed songs. Now the album sounds dated.

Today we’re on a very different track and going more for the energy that comes from playing something more raw and visceral and immediate. The orchestrations and arrangements are still sophisticated. But there are louder drums, and even the horns have distortion. But that feel is not exclusive to modern recording techniques or American aesthetics. If you see a group like [traditional Ethiopian trio and occasional Debo collaborators] Fendika they are really powerful. They put out all this raw energy — translated, Fendika means ecstatic energy — so I think the visceral element was also part of the traditional sound that, in a roundabout way, we are returning to.

When we were focused on an orchestrated approach it reflected a modernist take on Ethiopian music that was influenced by European ideals, whereas the rawer sound is inspired by traditional Ethiopian folklore. Getting back to Gétatchèw, his sound was not modern in the sense of an Albert Ayler — he was drawing upon [traditional] warrior songs.

AF: In the past 20 years a lot of Western listeners have discovered the so-called “Golden Age” of Ethiopian music through the Ethiopiques compilation series. In Boston we’ve had a number of concerts from the likes of “Golden Age” stars Mulatu Astatke and Mahmoud Ahmed. Of course, that sophisticated Addis Ababa sound is wonderful, but on the new LP you explore many other Ethiopian styles.

Mekonnen: One track that really stands out is “Hiyamikachi Bushi,” a song that comes from post-World War Okinawa. We kept the original melody but changed the time from 4-4 to 6-8 to give it a more Ethiopian feel. We are playing with pentatonic similarities between Japanese and Ethiopian music. Selassie sent soldiers to fight in the Korean war, and these men still appear at Ethiopian parades wearing their uniforms. Many fell in love with Korean women, and brought back melodies from Japan. A number of Ethiopian songs about this wartime experience were written in the ’70s and ’80s. It’s sort of a sub-sub-genre we thought it would be interesting to explore. Our accordionist Marié Abe took the lyrics and translated them into English. Then our lead singer Bruck Tesfaye translated them from English to Amharic.

AF: There’s also a Duke Ellington cover.

Mekonnen: Yes, and the origin of that song is imaginary. We know Duke was in Ethiopia in early ’70s — there’s an iconic photo on the cover of Ethiopiques Volume 4 where Mulatu Astatke is handing Duke a krar lyre and standing at the piano. Yet it seems to be a staged photo. Still: what happened at 4 a.m. after the gig? The (Addis Ababa) Police Orchestra was still active; surely Duke’s band joined them and came up with some sort of collaboration. So we took “Blue Pepper” from the “Far East Suite” and combined it with the Police Orchestra’s “Behasabe.”

“Kehulum Abliche” is based on Rafaad iyo Raaxo, a ’80s Somalian funk track by the Dur-Dur Band. It’s from a film they scored that we discovered through a friend in Ethiopia. We understand Dur-Dur are now in Denver, but we haven’t been able to track them down. I’m a part of the Nile Project and was born in Sudan, so it was nice to include an East African connection. Sudanese and Ethiopian music share melodies, rhythms, and they both use violins, accordions, and saxophones.

The “Oromo” medley is made up of traditional tunes by Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group. At the moment, there’s a conflict growing between the Oromo and the Ahamaric ruling class. In the last three months there has been a lot of violence on Oromo campuses. We didn’t know we’d be releasing this at a time of political turmoil, but the “Oromo problem” is always there. The medley honors that community.

“Yachat” is the most rocking, most punk song on the album. It comes from the Harar Police Orchestra. Harar is a Muslim part of Ethiopia — it’s a walled fortress city. We’re trying to shift the focus from the Christian, Amharic-speaking hegemonic culture which has been root of what we’ve been doing and branch out.

Danny Mekonnen (center, seated) and the Debo Band. Courtesy of the artist.

AF: Your last album was on Sub Pop, the Seattle label famed for its grunge releases. This time you crowd-sourced the funding of your record. How did it work out?

Mekonnen: We were really fortunate to work with Sub Pop the first time around. They gave us a modest budget and when we spent it all they gave us more money. Then they spent money publicizing the album. It’s all really easy. But you end up running a pretty deep tab, which you recoup through album sales. We’re still a long way from ever doing that and, if we ever did, our share of the profits would be about 17%. We funded this release through Pledge Music, so we had a completely mastered and sequenced album to deliver to a label.

We still wanted a label for distribution and infrastructure and we found a label ideal for us at this stage: FPE, a small company connected to Debo through our sousaphone player, Arik. FPE is run by the vocalist of Arik’s old hardcore band, Fat Day. The deal is really favorable to us. The album is already paid for by our fans, so there’s no issue of having to recoup costs. What we are left with now are PR expenses, and once we [earn] that back we’re splitting the profits 50/50, which is very uncommon. On top of that, we own the masters.

It took us four years between the Sub Pop release and this one. One reason it took that amount of time was because of the learning curve posed by putting out a crowd-funded album. Our manager is encouraging us to go back into the studio this year, so we’re thinking about going back to the pledge community. When you don’t release an album in four years, it’s like you’re starting over from scratch. An album gives you a platform — journalists write about you and there’s a social media buzz. We used Pledge Music, but also like KickStarter or IndieGoGo. The goal is adjustable, the timing is adjustable, and once you reach your goal the campaign turns from a “help fund us” project to a preorder option.

As for keeping a 10-piece band on the road, I’m not sure there’s an economic solution for that. A lot of larger ensembles are more successful in Europe, and it might take a grant to help us tour there.

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka and far beyond. He has won over ten awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.