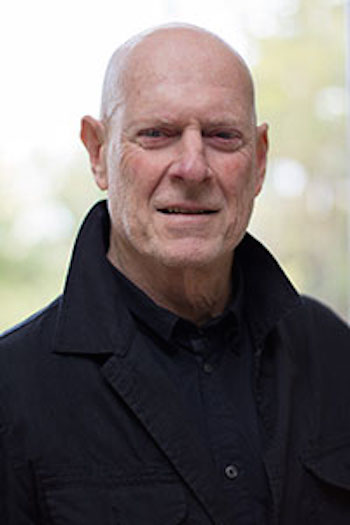

Fuse Remembrance: Peter-Adrian Cohen — 11/16/1939 – 3/7/2016

By Harvey Blume

Peter-Adrian Cohen

I got to know Peter only when he was already sick with cancer, not that he talked about it much. The illness was nevertheless background, though we advanced to the point where I could ask frankly about his health and he would answer honestly, always without self-pity, and often with a touch of humor.

If I cared to say that my osteoarthritis, the pain in my knees, was somewhat debilitating, limiting my ambition, I’d choke it back, since what he was dealing with was something a little more serious than hobbling and bad knees. (He did emphasize that one thing he especially detested about cancer is that it deprived him of skiing, which he had loved.)

He joked that many of his friends censured themselves, choosing not to complain about anything at all when he was around.

We talked about being Jews, about Israel, about literature. I grew up with Phillip Roth. He remembered the circle in his Zurich youth that worshipfully gathered around Berthold Brecht: Zurich bankers paying obeisance to the Communist playwright.

Though he admired Brecht, he did not much admire this toadying. And he did know his Brecht, far better than I. I complained to him that the movie The Lives of Others seemed false to me, because it depicted Brecht as a romantic poet whose lyrics could melt the heart of a hardened Stalinist. I objected that Brecht was never such a tender and romantic writer.

Peter informed me that I was mistaken, and that there’s a whole body of Brecht’s work that exists outside the corpus of what he’s best known for in English,

We always talked about books. He was reading Thomas Meacham’s bio of Jefferson, for instance, and relentlessly arguing with it. (I wonder what he would have made of Meacham’s more recent, to my mind, toadying, bio of the Bush family.)

I recommended Lawrence Wright’s Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David.

He took me up on it, and shared my enthusiasm.

We were the best sort of friends in the sense that we had enough shared language and enough difference to enrich each other.

Peter had written a much-produced play — To Pay the Price — about Yonatan Netanyahu, the younger brother of Benjamin, Israel’s Prime Minister, who died in the attempt to rescue Jewish hostages at Entebbe, in 1976. Peter, who retained a sort of complex and conflicted access to the Netanyahus, didn’t want his play produced again. He opposed Bibbi’s politics and didn’t want a play about Yonatan’s heroism to be construed as any kind of support for the reigning Netanyahu.

I thought he was wrong about that, arguing that a new production could be an excellent platform for him to air his views about the current Bibbi’s regime.

Peter gave me audio copies of his radio plays, which I enjoyed immensely: less politics, more free play of imagination, irony, humor.

We used to meet on Fridays at a certain spot. I miss him every time I go by it, and hardly only then; there are thoughts and feelings I’m unlikely to share, and many I won’t have, due to the end of conversation with him.

By Bill Marx

Like Harvey, I treasured Peter because of the infectious vitality and quality of his mind, the snap and crackle of his conversation. He spent chunks of his time in Boston (where he received what he described as excellent treatment for his cancer) and in Switzerland. Our talks in Davis Square, usually over a meal, often touched on variety of topics, but he rarely brought up his formidable health problems. Instead, he spoke with passionate animation about new trends in European politics and theater, the (usually) sad state of playwriting here, and his tireless efforts to have his scripts produced in Boston and New York (his work was often staged in Germany). I interviewed him in August 2011 about In the Name of God, his powerful drama about the enduring socio-psychological traumas of 9/11. The Nora Theatre Company in Cambridge gave the script a staged reading, as did a theater troupe in New York; there was a full production of the play in Germany.

A scene from the German production of Peter-Adrian Cohen’s “In the Name of God.”

Peter gave me a number of his plays to read: the historical drama The Court Jew, To Pay the Price (a script based on the letters of Israeli hero Yonatan Netanyahu, who was killed in action during Operation Entebbe; it almost got a 2007 Boston production at the New Rep but politics got in the way), and In the Name of God. These are complex dramas concerned with exploring the thorny moral quandaries at the center of intractable social problems. [Eventually, because of acrimony with the Netanyahu family, Peter decided to withhold To Pay the Price from production.]

One of Peter’s strongest creative inclinations was to reinvent the notion of the documentary play, to mix together imagination and fact in surprising ways. He talked about that goal in the Arts Fuse interview: “As I worked with this particular form — with what used to be called “documentary” theater — I found the form limiting. I realized the documentary form does not have to be anything — it’s a form like any other and therefore open to experimentation, expansion, and renewal.” A continual (and understandable) source of frustration for Peter was that he was better known here for his 1974 best-selling nonfiction work The Gospel According to the Harvard Business School than for his plays.

At our occasional gabfests Peter was always optimistic about what he was up to. He was constantly working at finding production opportunities for his scripts. He wrote discriminating theater reviews for The Arts Fuse and, in the face of my usual self-pitying bellyaching about the state of the magazine, he cheerfully offered up inspiration and possibilities. His puns were inevitably bad, and he relished making them. He deeply loved the theater, the arts, and his family. In his classic treatise on How to Grow Old, Cicero writes that when an old person dies “it is like a flame that diminishes and flickers away of its own accord with no force applied after its fuel has been used up.” For as long as I knew him, no matter how exhausting it became for him to live with his illness, there was nothing gradual about Peter — he burned hard and bright. The world is a darker place with his passing.

Tagged:

I know it’s been many years since Peter Cohens passing. I just read these tributes to him for the first time. They are beautiful and accurate.

I knew Peter for more than 20 yrs outside the arts. I miss him.