Book Review: Seeing “Eternity’s Sunrise”—Understanding the Vision of William Blake

In Eternity’s Sunrise, Leo Damrosch’s prose flows, filled with imaginative lucidity.

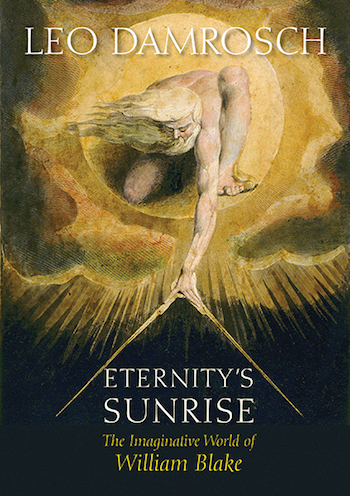

Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake by Leo Damrosch. Yale University Press, 344 pages, $30.

By Susanne Sklar

Long ago I had the good fortune to study William Blake’s poetry and painting with Jean Hagstrum, a great professor at Northwestern University, whose book William Blake: Poet and Painter has been a fine guide to Blake aficionados for over 40 years. Hagstrum’s lectures were a winged joy, helping us understand Blake’s words and images with the eyes of our hearts. Never did I think to encounter again such clear and imaginative analyses, but as I read the first beautifully written chapters of Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake, I was inspired to look even more carefully at Blake’s composite art. Professor Damrosch’s prose flows, filled with imaginative lucidity.

Long ago I had the good fortune to study William Blake’s poetry and painting with Jean Hagstrum, a great professor at Northwestern University, whose book William Blake: Poet and Painter has been a fine guide to Blake aficionados for over 40 years. Hagstrum’s lectures were a winged joy, helping us understand Blake’s words and images with the eyes of our hearts. Never did I think to encounter again such clear and imaginative analyses, but as I read the first beautifully written chapters of Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake, I was inspired to look even more carefully at Blake’s composite art. Professor Damrosch’s prose flows, filled with imaginative lucidity.

Leo Damrosch lets us know that his book is not a systematic biography; G.E. Bentley’s Stranger From Paradise is the authoritative one and Damrosch draws many of his aptly chosen anecdotes and details from that excellent tome. Calling Eternity’s Sunrise “an invitation to understanding and enjoyment” he guides our eyes through Blake’s illuminated work, carefully defining key terms (such as “Minute Particularity”); he discusses engraving and printing techniques, describes Blake’s personal and professional life, and interprets selected paintings and poetry in their historical and literary context.

The first half of Eternity’s Sunrise is superb, leading us (non-chronologically) from Songs of Innocence (1789) to Experience (1794) to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–91), followed by the “revolutionary prophecies,” America (1793), and Europe (1793). Initially, I was sorry not to encounter Visions of the Daughters Albion (1793) in this cluster of illuminated poetry, but Damrosch, like Blake, sometimes chooses to be non-linear in his explorations, inserting his interpretation of Visions in a later chapter about love and jealousy.

Damrosch reminds us that Blake’s Songs (of Innocence and of Experience) were meant to be sung, and though Blake’s renditions of them were greatly admired, no transcription of his melodies exists. I’m delighted by Damrosch’s ruminations about Blake’s pronunciation, demonstrating (by prosodic analysis) that his speech may have been akin to Mark Twain’s—as when “poor” rhymes with “more” (in Experience’s “Human Abstract”) and “g” is dropped from “sobbing” to rhyme with “robin” (in Innocence’s “Blossom” ). The poetry grows livelier when you try reading it aloud as if you were Tom Sawyer.

The world of Innocence becomes more palpable when Damrosch guides us through Blake’s organic designs, citing Erasmus Darwin’s Love of the Plants to show that sexual energy permeates all of life, every bud and blossom. Experience, of course is grimmer, but no less lively; Damrosch understands the importance of Blake’s contraries; the dynamic of joy and woe with which all must cope. He illustrates Blake’s main concerns about repressive patriarchy and social injustice with well chosen poems. The “mind forg’d manacles” of Blake’s “London” cripple us today. Throughout the world children live in terror and fear; religions create suffering; well-meaning people disregard injustice. Damrosch likens Blake’s understanding to that of the South African martyr Steve Biko who declared: “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

William Blake was not a political activist in the traditional sense. Though he admired America’s “Sons of Liberty” and was acquainted with Tom Paine as well as the radical publisher Joseph Johnson, Blake wanted to change the way we see, to alter basic assumptions. Liberty is spiritual and erotic, as well as political, and Blake’s print “Albion Rose,” depicting an exuberant man, nude, arms outstretched is, as Damrosch shows, Blake’s vision of Britain liberated as well as humanity (it might also be an idealized self-portrait). Liberation, however, comes at a cost in Blake’s America (1793) and Europe (1794) where the violence as well as the vitality of revolution is embodied in the character called Orc, bound naked on a rock like Prometheus.

“Blake’s symbols are dynamic, not iconic,” Damrosch observes, and this insight aptly illuminates the fluidity of revolutionary Orc (and by extension Blake’s other mythic characters). Blake’s fiery Orc can promulgate libidinal joy and/or terror; the streets of Paris ran with blood as Blake was engraving Europe. The oppressiveness of institutional religion may have been obliterated in France, but the worship of reason and material nature was dehumanizing. “In Blake’s view, the thinkers of the Enlightenment performed a necessary act of destruction,” Damrosch notes, “but they didn’t know how to reconstruct.”

From 1794 onward Blake’s writings grew increasingly complex. His symbolic characters, interacting on many levels, began forming their own mythopoetic system—from The Book of Urizen (1794) through The Four Zoas (1795–1804) to Milton (c. 1804), culminating in the illuminated masterpiece Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804–1821). Blake’s evolving system is as dynamic as Blake’s characters.

Damrosch is quite insightful about the nature of Urizen, the Zoa (life force) embodying reason. Fearing chaos (the sort promulgated by Orc) Urizen seeks stability, but he does so in totalitarian ways, as the jealous God of the Bible can do, promulgating “One command, one joy . . .one king, one God, one Law.” Totalitarian law stifles imagination and compassion, spreading misery throughout the earth. In Blake’s system imagination (embodied in Los/Urthona, a prophetic blacksmith), feelings and erotic energy (embodied in Luvah), and primal needs (embodied in Tharmas) must coinhere with reason, working together to serve divine vision, leading to life in what Blake calls “the Divine Body.” This is most apparent in Blake’s final prophecy, Jerusalem. And though Damrosch sensitively interprets the poem of that name that became a hymn, he, (like many intelligent critics before him) thinks Blake’s masterpiece is unreadable.

Damrosch is more comfortable with The Four Zoas, guided by its themes of love and jealousy, and with Blake’s Milton, a poem in which Blake clears psychological, erotic, and spiritual ground to unite with his poetic forbear. When commenting on Jerusalem, Damrosch likens it to both music and film, and alludes to critics who speak of “performing Blake.” William Blake lets us know that in his final non-linear prophecy, every word and every character is meant to suit “the mouth of a true Orator.” The poem is designed to be read aloud, and when read aloud in a group, with each reader cast as a different character, a montage of stories emerges. Blake’s fluid characters behave differently in different states of being (Ulro, Generation, Beulah, Eden/Eternity). Their fluctuating stories, layered with allusions as fascinating as the clues in the most difficult crossword puzzles, tell a composite tale.

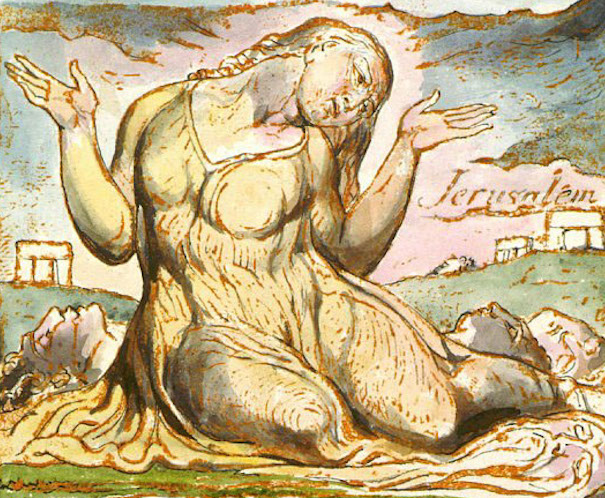

William Blake’s “Jerusalem: Druid Rocks with pitying figure of Jerusalem.” Copy A, Plate 92, detail (British Museum).

Chapter One is about Albion’s fall and Jerusalem’s banishment; Chapter Two has to do with Los (Zoa of Imagination) attempting to rescue Albion (with help of Eternal Cathedral Cities), and with Erin (a wise crone) attempting to rescue Jerusalem. In Chapter Three’s cacophonies, Albion’s disease of Selfhood infects Los, Jerusalem loses her mind in Satanic mills, and war overspreads the earth. Chapter Four begins with Jerusalem’s lament; though devoured by a dragon she rises (in plate 91’s design) while Los intrepidly labors, disempowering his Spectre, not integrating with it as Damrosch suggests. (The spectre, a batlike creature, fills characters with negativity, infests them with Selfhood, and severs them from divine vision). This clears the ground for Albion’s great awakening in which all things (including the reader) enter Eternity, human and divine. Like Blake’s Jesus we are unconfined by space and time in the state called Eden/Eternity. The great problem is the disease of Selfhood, not just the “Female Will” (discussed by Damrosch in a later chapter); the furious Female Will arises after feminine characters are negated, repressed, and whipped.

Blake’s characters are often misogynistic, but Blake himself has created a compassionate heroine, Jerusalem, the erotically active bride of Christ, who can orchestrate a mutually beneficial multinational economic system. She’s repeatedly banished by Albion, who is crippled by fear and greed, symptoms of Selfhood—and by the fury of those who’ve been oppressed, including her own shadowy “sister,” Vala (who is also known as Rahab and/or Babylon). In one of Blake’s most eloquent and uncannily prophetic speeches, Jerusalem confronts the powers that be (plates 78–79); it is she who must be reintegrated in Albion, in every creature, even rocks and trees. She becomes what Jacob Böehme (one of Blake’s visionary progenitors) would call the “Signatura Rerum”; every thing is, in Eden/Eternity, imbued with her name, connected with her to life in the Blakean “Divine Body” (plate 99). I think her story is “the golden string” around which the other stories constellate.

To enter fully into Blake’s imaginative world it’s necessary to have an understanding of his illuminated Jerusalem. Leo Damrosch has excellent insights about Blake’s illuminations in the late prophecies, and it would be grand to spend time with him going through those books, plate by plate. Make no mistake: Eternity’s Sunrise, beautifully written, is a good book; a more thoughtful analysis of Blake’s profoundest work would have made it an extraordinary one.

Susanne Sklar, a member of the Cumnor Fellowship in Oxford, is the author of Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ As Visionary Theatre (OUP, 2011). She writes and teaches at Oxford as well as Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Her email: ssklar@carthage.edu.

Tagged: English poetry, Eternity's Sunrise, Leo Damrosch, Susanne Sklar, The Imaginative World of William Blake, William Blake