Visual Arts Review: Clifford Ross at MASS MoCA — Reinventing the Sublime

The artist is savvy enough to know that beauty, and even the sublime, on their own terms are not enough to cut it in the competitive field of contemporary art.

Clifford Ross: Landscape Seen & Imagined. At MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, through March 2016. Clifford Ross’s Wave Cathedral, in Building 12, is on view through September 27.

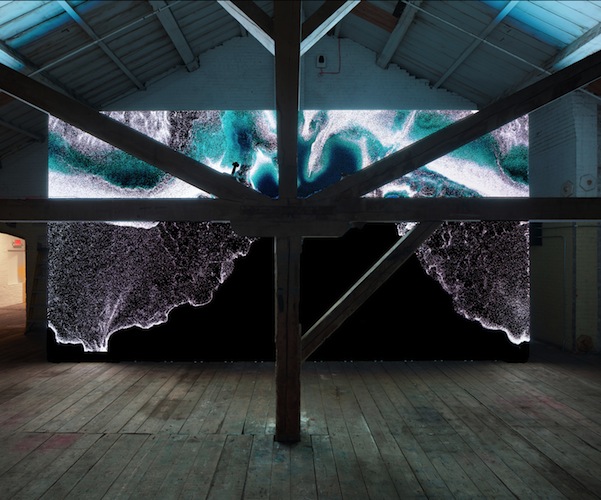

Clifford Ross, Wave Cathedral, 2015 (Installation view). Photo: Arthur Evans.

By Charles Giulano

The Clifford Ross exhibition at Mass MoCA Landscape Seen & Imagined combines large-scale straight and manipulated photographs and video works. The show begs the question of whether bigger is better. On its most direct level, the exhibition is filled with large, meticulously detailed, gorgeous, and enthralling images. That said, the pictures also also invite an “eat me’ “drink me,” tumble down the rabbit hole of brilliant manipulation and perceptual fragmentation. That excursion is triggered by a subtext that reexamines theories of landscape — the beautiful, the sublime, and the picturesque — formulated by Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant.

The artist, who has a B.A. in art and art history from Yale University (1974), is savvy enough to know that beauty, and even the sublime, on their own terms are not enough to cut it in the competitive field of contemporary art.

Entering the galleries you first see 75 x 130” Chromogenic color prints from Ross’s “Mountain” series, straight prints and matching views of a mountain range mirrored in the foreground by the glass-still surface of a lake. The scale, richness of color, tranquility and meticulous detail these images resonate with paintings by the 19th century American artist Albert Bierstadt. His work, viewed as exotic for its time, was created while the nation was relatively young and the wilderness was vast and pristine. Those epic paintings were acquired by Robber Barons who were becoming rich by transforming the land and ultimately despoiling it.

That gallery leads to a vast, broad space that soars two-stories high. The artist has designed a work to fit this enormous room. A negative of the same mountain view has been printed onto a series of vertical wood panels. The natural ground creates a sepia-like tone that is soft and subdued.

The work is too vast for such a narrow space. Even if you step back it is impossible to view the entire panorama from a central vantage point. From where you can comfortably stand the trees in the foreground are about the scale that we would encounter them in nature. Outdoors, the view would be “beautiful,” but indoors its audacity is shocking.

Back in the 1970s, 11×14” was considered to be a large print. Then there were Ansel Adams’s zone method prints, which we thought were giants.

That changed with the panoramas of Andreas Gursky and the acceptance of prints in the range of 81 x 140.” Of course, those large images, along with these gigantic works by Ross, raise vital aesthetic questions — does scale make a work more important or interesting? And does this attraction to the large make work of more ‘ordinary’ size less attractive to our eyes? The needs of vast industrial spaces like MASS MoCA, where curators are invited to install this kind of work, are exacerbating the trend. For now, the traditional standard of evaluating the artistic value of photographs — subject matter, quality of chiaroscuro, and composition — trumps the selling point that ‘bigger is better.’

Ross takes the process further, moving from a straight view of a mountain to blowing it up to scale. Then he goes on to deconstruction.

The notion of seeing a mountain from multiple perspectives is a rather old idea. Visitors to the MFA this summer viewed Japanese prints of Hokusai and his series “36 Views of Mt. Fuji.” The New York Historical Society displays the “Course of Empire” by Hudson River master Thomas Cole. The series of paintings displays changing views of a mountain as a part of its decline and fall narrative.

Ross gives this idea a post-modern update. We stand in front of a negative print of the same mountain we have seen earlier. At a right angle to this image is a vertical video triptych. The video zooms into a detailed view of the mountain, isolating a vertical rectangle of the woods in the foreground. This morphs into multi-colored panels of that vignette. The images are then shuffled, like a deck of cards, the design turning into a number of different configurations. The floating panels are then scattered irregularly and slice into each other. Like the pieces of a shattered stained glass window, the pictures eventually fall into the lake. The relatively brief video is looped.

Down the corridor are framed pullouts of the cut-up images in a range of monochromatic colors. One assumes that these are gallery-scaled collectables.

A short walk across the courtyard we ascend an outer staircase to the attic of Building 12. The space has been leased long term by the Clark Art Institute. This is the first time it has been used.

Raw and unfinished but broom clean, the attic, with its vernacular beam truss supporting the ceiling, emanates a powerful visual and aromatic sense of the simple, pragmatic beauty of the mill spaces. The main gallery, in bays between the vertical beams, displays the large (73 x 129”), horizontal, black and white archival pigment prints from Ross’s “Hurricane” series.

Installation view of “Clifford Ross: Landscape Seen & Imagined.” Photo: Arthur Evans.

To create these images Ross worked with technicians to design and build cameras capable of high speed, crisp resolution. Add to that technological challenge the act of having to brave the elements under extreme conditions.

The result is visually ravishing. The artist has been able to capture the nano-second crashing of waves. Piles of foam are frozen into sculpture-like stillness. The images evoke the seminal strobe photos of pioneer Harold Edgerton, but at a colossal scale and with crisper resolution. Contemplating these ‘fast’ shots of nature at its more ferocious brings Kant and his notion of of the sublime to mind: “…astonishment amounting almost to terror, the awe and thrill of devout feeling, that takes hold of one when gazing upon the prospect of mountains ascending to heaven, deep ravines and torrents raging there.” Or the ocean roiled by hurricane force winds crashing on the New Jersey shore.

In an adjoining attic space, on facing walls, are pixilated videos of those waves, their creation generated by algorithms. Your view is marred or enhanced by thick-beamed supporting trusses.

As a MASS MoCA neighbor I have been to the attic of Building 12 several times and always come away with different feelings and insights. The work grows on you.

Charles Giuliano, Founder/Publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell and Clark University.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Clifford Ross, Landscape Seen & Imagined, MASS MoCA