Classical Music Reviews: Andris Nelsons conducts Shostakovich, James Brawn plays Beethoven

This recording is the first of a partial Shostakovich cycle Andris Nelsons and the BSO are embarking upon, and it’s hard to imagine a performance of more impact, depth, and brilliance with which to begin such a series.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

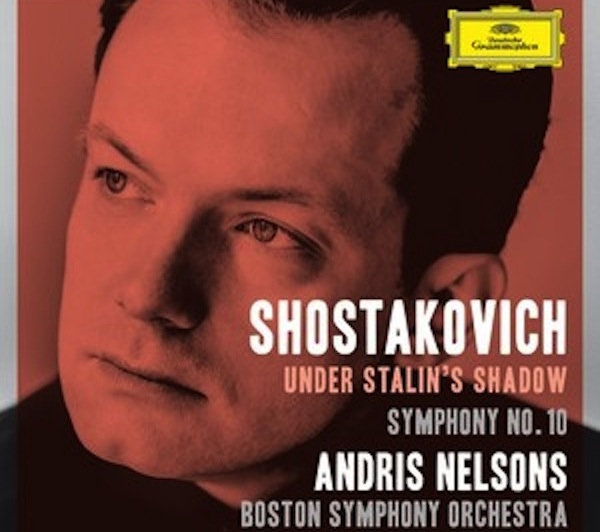

There wasn’t much that I didn’t like about Andris Nelsons’ account of Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony and the “Passacaglia” from the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) back in April. And there’s next to nothing that I don’t like about Deutsche Grammophon’s new album drawn from those concerts, Nelsons’ first major international release with the orchestra and the ensemble’s first appearance on the Yellow Label in eight years. This is the first of a partial Shostakovich cycle Nelsons and the BSO are embarking upon and it’s hard to imagine a performance of more impact, depth, and brilliance with which to begin such a series.

Not that it’s easy listening. Lady Macbeth was the crowning achievement of Shostakovich’s avant-garde youth, raucous and dissonant. Its staging was famously provocative, offending Stalin and resulting in the ominous Pravda verdict that Shostakovich was writing “muddle instead of music.” The Tenth Symphony dates from almost twenty years later, after the Stalinist purges, the Great Patriotic War, and the most precarious days of Shostakovich’s long relationship with the regime. While it ends in a blaze of triumph (or is it defiance? Or something else?), it’s chock full of ambiguity.

My introduction to the Symphony came courtesy of Yevgeny Mravinsky’s 1976 account of it with the Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) Philharmonic. That one’s about as raw, intense, and sensationally heartfelt a performance as you might expect from the orchestra and conductor who originally premiered the piece in December 1953. Nelsons’ reading is necessarily of a different stripe, cleaner and a bit less heart-on-sleeve, though technically more assured and possessing an overall more luxurious recorded sound. But Nelsons’ performance displays the same striking command of musical architecture, pacing, and an understanding of the Symphony’s dramatic goals as Mravinsky’s: he makes a powerful, convincing musical argument here that should put to rest, at least for a little while, the occasional complaints about his youth and unevenness as an interpreter.

Nelsons is very much his own man when it comes to Shostakovich. The Symphony’s big first movement, a sprawling, Mahlerian essay, unfolds a bit expansively — Nelsons’ timing runs about two-and-a-half over Mravinsky’s and nearly three minutes longer than Herbert von Karajan’s famous 1981 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic — but the BSO’s playing is never slack. Quite the contrary: Nelsons draws out orchestral playing of consistent, rigorous intensity that, in addition to maintaining the movement’s dramatic tension, has the effect of emphasizing the music’s deep reservoir of melancholy.

The short, slashing second movement doesn’t fly as briskly as it might – there’s the feeling of Nelsons holding back the reins just a hair – but it doesn’t lack for fury and violence. Rather, Nelsons’ approach here tends to ratchet up the level of terror and excitement. The third movement, which starts off with a strange combination of relaxedness and intensity that suits this music peculiarly well, offers bit of a contrast by way of mood, a mysterious brew of paranoia and defiance. In the finale, the BSO delivers a powerful reading of the movement’s long, anguished introduction that’s answered by playing of real crispness, character, and color in the alternating rollicking, fast sections.

Throughout the performance there are a host of magnificently played solos, especially from the orchestra’s principal wind and brass players. Principal flute Elizabeth Rowe, principal clarinet William Hudgins, and principal bassoon Richard Svoboda lead the way and James Somerville’s horn solos in the third movement are as finely etched as any I’ve heard in this piece. Timpanist Timothy Genis thunders brilliantly on the “DSCH” motto over the closing bars. Good as its many solos are, though, this is a Symphony that lives or dies on a cohesive orchestral performance, and much credit is due Nelsons and the BSO for realizing it with the unanimity of expression, depth of feeling, and technical proficiency they bring to the score.

For an opener, the grim “Passacaglia,” which comes from the second act of Lady Macbeth, strikingly anticipates the mood of the Symphony’s opening movement and makes for a powerful introduction to the larger work. I’ve rarely heard a cacophony like the scream that opens it played with more power and — most impressively — clarity as the BSO managed live in April and is very well documented on this recording. The whole piece is a rather tough nut to crack, unrelentingly dark and pained, a potent reminder of a time and place not nearly as far removed from our modern world as we might like to think.

As I’ve noted previously, Nelsons is a young conductor and, in some repertoire, he’s still growing as a conductor. But the music that he’s really got under his fingers he leads as well as anybody. So it is here: these are modern reference recordings of these pieces and augur good things for the cycle’s continuing installments (Symphonies nos. 5, 8, and 9 next spring; nos. 6 and 7 in 2017). Also, if you live within driving distance of Symphony Hall, you should probably consider snapping up tickets to those upcoming performances. Based on this disc (and last April’s concerts), they may well turn out to be the sort of musical events we talk about for years to come.

*****

Pianist James Brawn — he has both the technical and interpretive chops to make this music breathe and compel.

One of the joys of reviewing new releases last year came courtesy of the first three installments of James Brawn’s traversal of the thirty-two Beethoven piano sonatas. There are, of course, many fine and historic accounts of these iconic works, but, in the first three volumes, Brawn’s fresh interpretations of the warhorses and reminders of the graceful wit of the smaller sonatas made (and left) a strong impression. The fourth album of his “Beethoven Odyssey,” out now on MSR Classics, continues this happy trend.

In all, there are five sonatas on the disc, including nos. 15 (“Pastorale”) and the great no. 27 (op. 90). From a sheerly technical standpoint — quality of tone, clarity of articulation — Brawn reminds me most in these works of Daniel Barenboim. There’s an effortlessness to his playing that seems to grow with each “Odyssey” installment. Listen, for instance, to the Mozartian sparkle that emanates from the E major Sonata no. 9 (op. 14, no. 1): Brawn’s voicings are beautifully balanced and his articulations rhythmically alive. Beethoven isn’t always the most lyrical of composers but you wouldn’t know it from this performance: in Brawn’s hand, the Sonata’s songful moments really flourish.

Many of those same characteristics are evident in his performance of the D major “Pastorale” Sonata (op. 28), though, personally, I prefer a livelier tempo in the first movement and wished for a bit more of a spark in the quicksilver Scherzo. Even so, the slow movement didn’t lack for character or forward momentum and, when Brawn wants to move along at a good clip, he’s more than capable: the closing pages of the Rondo balance impressive speed, precision, and lightness of touch.

As with Brawn’s pairing of the 19th and 20th Sonatas in Volume 2, perhaps the greatest charm on this album comes courtesy of hearing the 24th and 25th Sonatas in succession. The former, in F-sharp major (op. 78), sometimes goes under the moniker “A Therese” and is about as unsettled a piano sonata as Beethoven wrote: coming, chronologically, after the otherworldly “Appassionata,” there’s the sense of a composer figuring out in what direction, exactly, to go next. Brawn plays the piece relatively straight — his adherence to the dynamics and articulation markings in the score is mightily impressive in all of these sonatas — and, in the process, lets “A Therese’s” quirkiness speak for itself. The music’s geniality, despite sharing not a few stylistic quirks with its predecessor (though on a much lower level of intensity), comes across strongly, nowhere more so than in the skipping two-note gesture that crops up humorously throughout the finale.

And the G major Sonata (no. 25, op. 79) offers more in the way of high spirits and goodwill. Brawn delivers playing of lively energy and great mirth in the outer movements (especially the first) plus a reading of real warmth and tenderness of the short second.

The E minor Sonata (no. 27, op. 90) caps things off glowingly. As is the case with “A Therese,” this sonata also followed a few years after a big (named) antecedent, in this case the E-flat major “Lebewohl.” Likewise, it shares a quizzical formal structure, falling in two movements, the first of which is something of a distillation of Beethoven’s “Heroic” style: filled with dramatic outbursts; alternating passages of great tension and intensity with tender, introspective moments; and so forth. The finale is much its opposite, about as folk-like and rhapsodic a movement as one finds in Beethoven.

Brawn turns in a strong reading of the opening movement, but the focus of his performance is the closing one. This is music that shrewdly plays to all the strengths Brawn demonstrated so well on the other pieces on the disc: textural clarity, heart, a deep understanding of the score’s structure, and beauty (of tone, articulation, and lyricism, especially). There’s a nice variety and flexibility in Brawn’s tempos, too, so that nothing really lags even if, at eight minutes, this is a performance that’s a bit over the average on timing. After listening to it a half-dozen times, I’m left with no real complaints: Brawn has both the technical and interpretive chops to make this music breathe and compel.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andris Nelsons, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon, James Brawn

Now that the BSO has just extended Andris Nelsons’ contract to a full eight years we have the distinct prospect of Nelsons having the time to record the full cycle of all 15 of Shostakovitch symphonies*. (plus ancillary concerto’s, incidental music, overtures, etc ). This would give both BSO fans and audiophiles something to really get excited about.

* Nelson’s reprogrammed the performance of the Shostakovitch 10th Symphony to stunning exclaim last weekend at Tanglewood. . . .