Classical Music Review/Commentary: BSO / Pianist Kirill Gerstein – Whose America?

The BSO’s Americana concert could only provide four beautiful snapshots of a very complicated landscape.

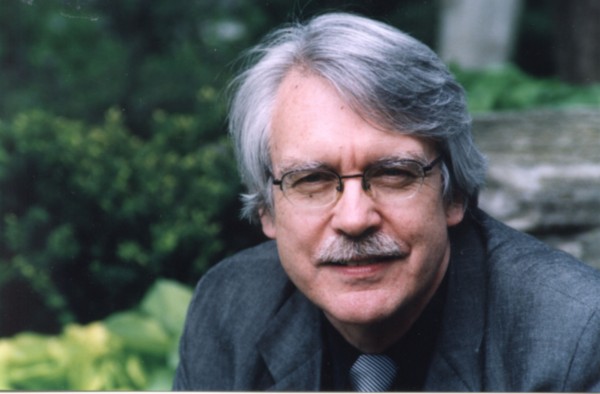

Kirill Gerstein — on his way to becoming the consummate Gershwin interpreter of this era. Photo: Marco Borggreve.

By Steve Elman

[Disclosure: I received press tickets to this event from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and I occasionally work as a fill-in announcer on WCRB.]

The kickoff of the Boston Symphony’s summer residence at Tanglewood was on Independence Day eve, July 3, and it was one of the most beautifully-curated programs of the entire summer season. Each of the four works on the bill spoke eloquently on its own, and each had a lot to say to the other pieces. Their mutual resonance was emphasized by first-class interpretations led by Canadian conductor Jacques Lacombe, and some stellar soloists, including pianist Kirill Gerstein.

The theme was Americana, as it almost had to be that weekend, but this wasn’t a flag-waving celebration of the Fourth. It went deeper and wider than that, with serious questions about the dissonance between the country’s aspirations and the realities lurking just beneath the surface of the music. Whoever was responsible for putting these pieces together deserves more than just kudos — he, she, or they merited recognition in the printed program.

Here’s a bird’s-eye view of the richness of the evening, taking the works in chronological order: George Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F, from 1925, embodies the very essence of Jazz Age New York optimism, untempered by the disillusionment of the World War to come; pianist Kirill Gerstein cannily looked backward and forward in his deeply thoughtful performance. Mid-war work by Aaron Copland, his Lincoln Portrait from 1942, puts the president on a pedestal and cushions some of his most sobering words about the USA with majestic music; Shakespearian actor John Douglas Thompson was the narrator, filling in for Jessye Norman, who had to cancel because of illness. Duke Ellington’s Harlem, from the 1950s, was an attempt to burnish and celebrate the neighborhood’s reputation from the perspective of someone who loved what it was and what it had been. The concert opened with the most recent composition, John Harbison’s Remembering Gatsby, from 1985; it brought out all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s skepticism about the American Dream by juxtaposing a peppy twenties-style fox trot with dark and dramatic masses of sound from the biggest orchestral forces of the night.

The Harbison work neatly tied up both ends of the program – Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby comes from the same year as Gershwin’s Concerto, and Harbison (who knows his jazz and pop as well as his classical) manages within a seven-minute showpiece to frame music that was “modern” in the twenties with music that is modern by contemporary standards. The basic material was salvaged from his Gatsby opera, a project he shopped to universal indifference in the early ‘80s (it finally came to the stage more than a decade after Remembering Gatsby had its premiere). The sweep of Jay Gatsby’s ambition and the hollowness at his core are front and center from the first thunderous chord, but the piece vacillates from dark to light as Harbison calls on a small “society” ensemble within the orchestra to play and embellish on an original tune that would be comfortable in the repertoire of the Jean Goldkette band or the Coon-Sanders Nighthawks – just the sort of thing that would have accompanied the dancers at one of Gatsby’s grand parties.

It was particularly inspired of Harbison to give the lead in the dance combo to soprano saxophone, and Mike Monaghan got the feel just right, old sport. Associate Concertmaster Tamara Smirnova and other members of the combo, probably including tubist Mike Roylance, trombonist Toby Oft, and possibly pianist Bob Winter, were all spot on, right down to a final wink by the combo after the orchestra has its final prediction of the doom to come. However, the size of the forces and the brevity of the piece make it a bit anticlimactic. Someone should commission Harbison to add two or three more pieces built on the opera’s music so that Remembering Gatsby could be transformed into a full-length suite.

Kirill Gerstein then joined a somewhat smaller BSO for Gershwin’s Concerto in F. Gerstein’s background – Russian-born piano virtuoso who honed his jazz chops as Berklee’s youngest-ever undergraduate – has prepared him to be the consummate Gershwin interpreter of this era, and he is well on his way to that status. Since I saw him play Rhapsody in Blue at the Performance Center in March 2012, I’ve been waiting to hear him play the concerto, and this performance did not disappoint. The first two movements were as good as any I’ve heard, giving the music the nuance and delicacy it deserves, trumpeting and caressing those great melodies without a hint of condescension. In an interview with WCRB’s Brian McCreath, Gerstein, with real insight, pointed to Franz Liszt and “the Russians” (meaning Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, probably) as inspirations to Gershwin, and he emphasized his point musically by adding a bracing chromatic run to the written material at his first entrance. And he wasn’t finished there. In the middle of the second movement, he added a full minute of original bluesy piano, firmly rooted in Gershwin’s melodic material, but adding some post-war jazz harmony. And throughout, he gently massaged his solo passages away from the stiffness that characterizes so many Gershwin performances towards an easier, proto-swing feel, with Lacombe’s conducting in perfect harmony. The first part of the third movement went a bit awry – in his first entrance, Gerstein rushed the tempo and it took a minute or so for soloist, orchestra and conductor to synch up. The intensely staccato nature of the music at that moment emphasized the flaw. But all was well by the time the piece reached its smashing conclusion. The other soloists — Smirnova again, oboist John Ferrillo, flutist Elizabeth Rowe, and especially trumpeter Thomas Rolfs — handled their roles beautifully. I can give no better examples of conductor Lacombe’s sensitivity to the music than to point to his handling of the dramatic rests that Gershwin places just before the final bars of each movement; Lacombe knows how to make even those silences expressive.

Conductor Jacques Lacombe — sensitive to every nuance in a wide-ranging performance. Photo: Steve J. Sherman.

The BSO has not yet recorded the Gershwin concerto; in fact, the orchestra relegated the work to Pops programs until a Carnegie Hall concert by the big band in 2005. It’s high time for this gap in their discography to be remedied, and Gerstein is the soloist I’d nominate. To round out the program of my fantasy CD, I’d suggest that the orchestra restake its claim to two other great jazz-influenced piano concertos – Aaron Copland’s Piano Concerto, which the BSO premiered in 1927, and Yehudi Wyner’s Chiavi in mano, which it commissioned and premiered in 2005, the same year it took up Gershwin’s.

After intermission on July 3, the orchestra played a work that is much more firmly established in its repertoire — Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, with narrator John Douglas Thompson stepping in for Jessye Norman. This is music that nearly elevates Abraham Lincoln to secular sainthood coupled with reverent excerpts from Lincoln’s speeches and writings. Unfortunately, I think the standard approach of most narrators who perform it (including that of Mr. Thompson) is somewhat off-base. Copland supplies plenty of grandeur in the music itself; the narration, I think, ought to provide something of a contrast to that grandeur, a reminder of Lincoln’s rawboned personality. Copland frames each of four Lincoln quotes with a spare, clean introduction (example: “When standing erect, he was six feet four inches tall, and this is what he said.”). I think narrators should give “different voices” to the framings and to Lincoln’s words, and both of those voices ought to have direct, vernacular style. Thompson read all the text as if it had been engraved on stone tablets, which somewhat reduced its power to speak to a modern audience.

But the words DO speak, if an audience can hear them as they were intended, eloquent but plain-spoken: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.” “It is the eternal struggle between two principles, right and wrong, throughout the world.” “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.”

The closing work was Duke Ellington’s Harlem, one of his best extended pieces and one of the few that lends itself well to adaptation for symphony orchestra. The BSO played Luther Henderson’s 1955 orchestration, which smooths out some of the original edges and cushions some of the music with strings. A saxophone section was added to the orchestra for this piece — Mike Monaghan and Greg Floor playing altos (and doubling clarinets, I think), Dennis Cook playing tenor, and Bob Bowlby, channeling Harry Carney on baritone. John Chudoba also joined the group to provide screech trumpet effects. The piece is episodic and, in less sensitive hands, it can fall apart depicting (as Ellington says) “many facets from downtown to uptown, true or false . . . upbeat parade . . . floor show . . . sermon . . . funeral . . . Civil Rights demandments . . . march onward and upward” and “jazz spoken in a thousand languages.” Again Lacombe demonstrated how sensitive he is to musical transitions, making sure that tempo and mood changes were logical and powerful. And the orchestra players themselves demonstrated how far classical musicians have come in their understanding of jazz feeling. Pizzicato strings got a banjo feeling just right in the floor show. Trombonist Toby Oft and a pair of clarinetists (Associate Principal Thomas Martin and Mike Monaghan, I think) played the “counterpoint of tears” from the funeral with true soul. And the orchestra’s percussionists (Will Hudgins, Daniel Bauch, Kyle Brightwell, and Matthew McKay) let it out in the closing moments when Ellington “gives the drummers some,” with trap kit, congas, timbales, and tympani all making a very joyful noise. That conclusion is triumphant, as Ellington is so often, holding back his personal bitterness at the long struggle for African-American equality and for “legitimate” respect for his own music.

John Harbison — His “Gatsby” miniature deserves some companion pieces.

There they were at Tanglewood, musically and in person — all those Americans, the skeptics and the sincere, the sophisticates and the casual picnickers, the glorifiers of ethnic culture and the immigrants reaching for the stars, the skilled artists doing their best to communicate and the multitaskers embedded in their smartphones, Honest Abe and the ones who live with the legacy of his time.

I saw more Americana while I was in western Massachusetts on Independence Day weekend — two displays of the Confederate Stars and Bars, both on pickup trucks. One was a flag decal. The other was a full banner on a mobile flagpole, waving proudly in the draft of the truck’s speed. I’m not clairvoyant, so I’ll avoid any interpretation of those displays. But those flags reminded me that the BSO’s Americana concert could only provide four beautiful snapshots of a very complicated landscape.

More: The entire BSO concert of July 3, 2015 will be available for on-demand listening throughout the next twelve months via the WCRB website. Brian McCreath’s extended interview with Gerstein can be heard through this SoundCloud link.

For a comparison performance of Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F, I recommend the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra’s recording, with Michael Tilson Thomas playing the solo part and conducting. For a comparison performance of Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, I recommend the London Symphony Orchestra’s version, with Henry Fonda narrating, conducted by the composer. Ellington directed one recording of the Henderson orchestration, on his 1963 LP The Symphonic Ellington. All of these performances are available via Spotify; to find Harlem, search for “Symphonic Ellington,” and choose “Harlem – Remastered.”

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.