Arts Fuse Appreciation: Ornette Coleman’s Horn of Plenty

So there was the Ornette Coleman Quartet, leading off the final side of vinyl with a cut that changed my life, “Lonely Woman.”

Ornette Coleman — Photo: Michael Hoefner.

By Milo Miles

When describing a lifetime experience with a top artist, it is customary to report that you were thunderstruck by the master’s finest obscure work – it makes you seem exceptional, perceptive, at least not-ordinary. The late Ornette Coleman captivated me with a piece that has likely snared more fans for him than any other. But with the passage of 40 years, the medium that contained it can now seem rather exotic.

In 1973, I was a music fan just starting to know how little I knew about music history. To make the odd jobs and the last summer staying at my parent’s house more bearable, I resolved to dig into jazz with the just-released Smithsonian Guide To Classic Jazz (my father was a fan of the institution’s magazine). I hadn’t realized how unusual the seven-LP set was. It not only covered jazz from the foundations in New Orleans until roughly the mid-‘60s, it also included material from a batch of labels, unheard of at that time. Almost as unlikely, the set was selected and introduced with liner notes by the venerable and eclectic critic Martin Williams. He had infallible ears for tracks that caught the essence of a performer or a style, though like all mortals he began to falter as he approached contemporary approaches. (Oddest lapses: George Russell and the AACM do not exist; John Coltrane is most important as a Miles Davis sideman.) No hesitation, though, when he wrote in 1959: “I believe that what Ornette Coleman is playing will affect the whole character of jazz music profoundly and pervasively.”

So there was the Ornette Coleman Quartet, leading off the final side of vinyl with a cut that changed my life, “Lonely Woman.” The elongated beats from drummer Billy Higgins and bassist Charlie Haden presented her walking down the sidewalk; you could almost see the hat swinging beside her in her hand. When Don Cherry’s cornet and Coleman’s alto sax chimed in together, the piece became a documentary of how she came to be lonely, a sad tale without a touch of sentiment. When Coleman soloed, it was the lonely woman’s monologue on her condition, her regrets, her yearning, her flashes of fury. You feel you know everything about the lonely woman when Higgins and Haden send her away down the street, after not quite five minutes. Not a problem that “Lonely Woman” was inspired by a painting Coleman saw in a department store. Better that way, even.

The other two Coleman selections were not as revelatory. Worst, the excerpt from Free Jazz presented the same scribble of sounds I had always associated with the style (to this day it seems the most eat-your-peas of his masterpieces). But while I could not have articulated it at the time, “Lonely Woman” had altered the way I would hear every jazz performer after – hell, every performer doing music derived from African-American sources and the African Diaspora in general. “Lonely Woman” let me hear the connections among playing an instrument, singing, and straight conversation in languages you did not understand – communion in sound without words. Coleman’s improvisations are free like the deepest blues are free, like the way the railroad trains he grew up next to talked to him in the night.

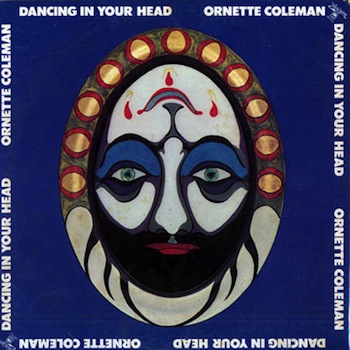

For me, the other singular turning point in conversing with Ornette came about five years later when I was first listening to jazz in the big city. I didn’t appreciate Skies of America and Science Fiction as much as I would later. They seemed a shade old-fashioned, almost conventional experiments. I was so certain of Coleman’s connection to rural roots that I was sure he shouldn’t be dealing with electricity and fusion. Then I heard Dancing in Your Head. May sound strange, but I don’t play records over and over again, nothing else for two days. Don’t do it. Not since the first time I put on Dancing in Your Head. Love me some Agharta and Jack Johnson, but Dancing in Your Head and the refinements, extractions, and expansion of Prime Time that followed are my brand of fusion. Coleman even made the case through his late-period reunion with the surviving Quartet members, that, amplified or orchestrated or playing in the middle of a wheatfield, his conversations cannot be stuck to a date.

The final night of the Newport Jazz 50th Anniversary Festival in 2004 was the last of the three times I heard Ornette Coleman on stage. And the only time he offered an acoustic version of “Lonely Woman.” I lay on my back, listening to Ornette do the monologue solos – fresh but not a demolition of the original. A vicious thunderstorm had just missed the area and there was nothing but lacy clouds and the sound of “Lonely Woman.” Were the clouds over Newport, R.I., or over Livingston, MT, those decades ago? The moments fused. Ornette Coleman again erased all the barriers. While he played, it wasn’t just free jazz – everything was free.

Milo Miles has reviewed world-music and American-roots music for “Fresh Air with Terry Gross” since 1989. He is a former music editor of The Boston Phoenix. Milo is a contributing writer for Rolling Stone magazine, and he also written about music for The Village Voice and The New York Times. His blog about pop culture and more is Miles To Go.