Dance Commentary: Misty Copeland, Ballet, and Race

Tomorrow, Misty Copeland will be American Ballet Theatre’s first African-American ballerina to perform the lead role in Swan Lake in New York City.

African-American ballerina Misty Copeland made her debut as Odette/Odile in “Swan Lake” during the ABT’s tour in Australia. Photo: Darren Thomas.

by Janine Parker

Perhaps you’ve heard the good news: At American Ballet Theatre’s June 24 matinee performance of Swan Lake, Misty Copeland will be the company’s first African-American ballerina to perform the lead role of Odette/Odile in New York City.

But there was some bad news accompanying that, too: Please read above sentence.

That this is news, in 2015, is what’s bad. More than half a century ago Dr. King gave us the view of his promised land and Brown vs. Board of Education made segregation in public schools illegal. Yes, there has been much progress — in her commencement speech at Williams College earlier this month, Ursula M. Burns (the chair of Xerox, she’s the first African-American female CEO at a Fortune 500 company) told the graduating class that if they’d seen the movie Selma, “…you can appreciate how far America has come.” She noted that we voted in a black president, “not once, but twice” — but went on to warn, “As you leave this serene campus, you’ll realize that there is something very wrong in America…Very telling [are] the incidents of killings of black men by those sworn to protect them.“

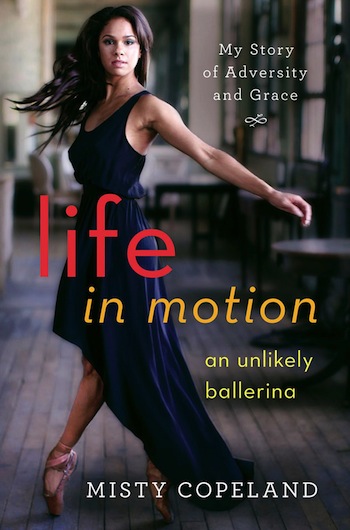

Still, the continued march, sometimes crawl, toward equality can be seen in the growing diversity in corporations such as Xerox, as well as in many sports, and in the arts as well. But the Misty Copeland story is another reminder that we’ve a long way to go in the ballet world. (And in case you’ve somehow missed it, there has been quite a lot of press and attention about this young artist, some of it coming from Copeland herself; last year she published her Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina. To clarify, the June 24 performance is not Copeland’s debut in the role; she performed it last summer with ABT while on tour in Australia and in April as a guest with The Washington Ballet.) Certainly, as it is my field, I am especially conscious of this issue in respect to our ballet stages, but in any event I am struck, at most performances, by how few bodies of color are up there. In this otherwise mostly-mute art form, this disparity can be quite loud.

In 1969, the year after King was assassinated, Arthur Mitchell, a black dancer who had gained prominence performing with New York City Ballet, and former dancer Karel Shook (a white man who as a teacher was known to be particularly supportive to black students) founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Within a few years —thrillingly, quickly, and incisively — DTH changed the playing field in this rarefied art form, offering classical training and professional opportunities to many talented black ballet dancers. And yet, though it’s hard to imagine where’d we be if the company hadn’t come along when it did, its continued existence can be seen as something of a catch-22 situation: do we still “need” a ballet company that is primarily, and purposely, composed of black and brown dancers? Does it create another kind of segregation? Does it keep those dancers from joining other companies, which could help those companies achieve greater diversification? We circle back to the recognition that there’s no guarantee that DTH dancers, should it not exist, would get into other companies. There’s only so many slots, and there are hundreds of dancers vying for each of them. Indeed, in 2004, due to financial difficulties, DTH entered a nearly decade-long hiatus; in a 2007 article, Gia Kourlas reported in The New York Times that of the now-jobless dancers, only one made “…a successful transition to a prominent ballet company.”

That dancer, Tai Jimenez, landed at Boston Ballet, where current artistic director Mikko Nissinen placed her right at the top as a principal dancer. To be sure, positioning dancers of color high in the ranks is an important and positive step toward equality in the ballet world. To that point, one of the notable “Misty moments” happened in 2012, when The New Yorker dance critic Joan Acocella, discussing in part Copeland’s status in ABT as a soloist, wrote “The company should have started pushing her hard long ago, partly just in order to help achieve the ethnic balance that classical companies so glaringly lack.” Acocella ended the article unambiguously: “Now they should promote her for artistic reasons as well as political ones. She deserves it.”

One can perhaps argue that ballet’s ethnic disparity arises from the fact that ballet is relatively young in the United States; though it’s centuries old in Europe and Russia, American audiences weren’t introduced to the art form until the early 20th century, and even then it was via touring companies. In 1963, when King gave his “Dream” speech, American Ballet Theatre was about 23 years old, New York City Ballet only 15, and while segregation was beginning to be dismantled, its legacy of exclusion was deeply embedded in our culture. This oft-described “lily-white” dance, born in the courts of England, France, and Italy, was, at one time in the US, literally forbidden to potential black students in some cases. For some, ballet continues to be figuratively forbdidding.

This sometimes real, sometimes imagined barrier is a source of intense frustration for many today. “Classical ballet is an art form for everyone,” Ballet West’s artistic director, Adam Sklute told me over the phone recently, not “…an art form purely for northern European caucasians in any way, shape or form.”

This isn’t a new thought in the field. In 1957, New York City Ballet premiered the abstract ballet Agon; in its featured duet choreographer George Balanchine cast Mitchell with a white dancer, Diana Adams. Balanchine, a Russian emigré, likely knew that some audience members would be offended by a black man touching a white woman, never mind grappling with her, as in the Agon pas de deux, with an often rough intimacy. With this silent language, volumes were spoken.

Yet Mitchell then — like Copeland now — was one of very few black ballet dancers who had both found their way to the top and been allowed to dance there. Raven Wilkinson, who danced with the Ballets Russe de Monte Carlo in the 1950s, had an especially precarious time when the company toured the South; as a light-skinned African-American, she often “passed” and could perform. But when she was “discovered” she’d have to move to another motel and sometimes that meant that she didn’t dance (Wilkinson would not lie about her race, but the company didn’t announce it). Eventually, as she recounts in the upcoming documentary Black Ballerina, it was suggested that it was time for her to leave the company altogether. “Someone came to me and said ‘you’ve gone as far as you can in the company…’ ” Wilkinson remembers, “ ‘after all, we can’t have a black White Swan.’ ”

In 1981, when Boston Ballet performed Pierre LaCotte’s reconstruction of the 1832 ballet La Sylphide, two of the dancers, Augustus van Heerden, who is black, and Stephanie Moy, who is Asian, weren’t cast; LaCotte insisted that his reconstruction must be “historically correct” in all ways, and it was widely understood that this meant ethnicity too. Laura Young, a former longtime principal with Boston Ballet , recently told me that it was shocking for other company members, who up until then had felt a sense of pride about having at least some diversity in the group.

In Black Ballerina, Virginia Johnson, the former DTH star who is now leading the company, corrects this “historically correct” notion, particularly when it relates to corps de ballet work: “The identicalness of ballet is not that you literally look the same, but that you embody the same intention, the same movement.”

“What Arthur Mitchell did was historic, certainly, and had a great impact to shatter the notion that African-Americans didn’t have a place in the ballet world,” Septime Webre, artistic director of The Washington Ballet said to me during a recent phone conversation. “There was just no way you could see DTH and not realize that you were on the wrong side of history if you [thought] that a ballet company, that Odette, should be lily-white.”

In 1992, following the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, the now-defunct Boston Phoenix published a special edition entitled “Under the Skin;” for the arts section, I wrote about ballet and race in America (the subtitle: “If dance is a universal language, why are ballet companies so white?”) and included some basic demographics culled from a sampling of companies. I asked each company for the number of dancers in the most recent season then how many were from a minority group, that is, Asian, Black or Latino. For this piece I contacted the same companies to see where we were 23 years later. Here are those figures:

Ballet West:

1992: 38 dancers total; 1 minority.

2015: 39 dancers total; ?? minorities — according to Joshua Jones, the company media relations contact, now the company “does not collect this information.”

Boston Ballet:

1992: 47 dancers total; 10 minorities.

2015: 69 dancers total; ?? minorities — according to senior public relations manager Toni Bolger Geheb, the company collects the information but only for EEOC purposes.

Houston Ballet:

1992: 56 dancers total; 8 minorities.

2015: 56 dancers total; 17 minorities.

Pacific Northwest Ballet:

1992: 46 dancers total; 5 minorities.

2015: 46 dancers total, 11 minorities.

San Francisco Ballet:

1992: 68 dancers total; 10 minorities.

2015: 70 dancers total; 24 minorities.

The numbers that were provided to me demonstrate improved diversity while the non-disclosing practices indicate increased sensitivity to identity and privacy, ideas that have become very important in recent years. One could argue that without making the number public a company could “hide” behind the issue, but it certainly doesn’t seem to be the case with Ballet West, which Sklute is determined to diversify. He told me that before he took the helm in 2007, “there were no women of African descent in our company and [since he’s been there] three have moved through the company…I’m all for expanding ethnic diversity in my company; I would like to see it in the entire art form, but I figure I can only control it in my company.”

It’s this kind of plowing forward within individual companies that is crucial — even in a historically-homogeneous state like Utah, which is also beginning to see growing diversification in its citizenry. “There are all kinds of interesting and fascinating reasons why diversity is building in the state of Utah,” Sklute noted, “but our company I felt needed to, in a funny way, lead the way into what we were looking at in terms of ethnic diversity…so we’re not a representation of our community, really, because we actually have more ethnic diversity in the company than the community does.”

Although it’s situated in a strikingly multicultural area, Webre too has worked hard to build up the diversity within his company. “It’s been important to me to have The Washington Ballet…to the degree that it’s possible, reflect the complexion…of Washington, D.C.” To Webre, this isn’t some kind of politically-correct PR statement, but a serious goal. “I think if the art form is to survive, people have to see themselves on stage…what we do as ballet dancers, we’re just showing the audience themselves and how great they can be, we’re like a metaphor for them…”

The fate of the ideal — American ballet companies that are as equally diverse as the population — hinges upon the development of future dancers. Now, one of the admirable strengths of many of our companies is their multinationalism, and I wouldn’t want that to go away; but alongside the Brazilian, Chinese, Cuban, French, Japanese, (and etc.) dancers, we need many more Americans of all ethnicities who have been highly-trained in classical ballet. “We need to train a lot of dancers to get that small group that’s going to rise to the top,” said Webre.

Indeed, all the companies mentioned here (and many, many more in the US) have programs that introduce dance to schoolchildren in surrounding communities — with a strong emphasis on outreach to underserved populations — as well as “bridges” that enable students selected from those programs to begin serious classical training within these company academies. (Boston Ballet’s excellent version, CityDance, is nearly 25 years old; I had the pleasure to teach some of the students many years ago.) Each year, The Washington Ballet’s 15-year-old DanceDC program, in partnership with the public schools, teaches 750 second- and third-graders pre-ballet classes twice a week, throughout the school year. From there, 75-80 students are chosen who, as Webre said, “meet certain criteria of professional potential, enthusiasm, self-discipline and citizenship” and, through the EXCEL! program, are given full-year scholarships to train at The Washington Ballet’s academy. And for those who continue on, support is there as they need it; Webre reports that 65% of TWB’s current student population is at or below the poverty line and their tuitions are thus fully or heavily subsidized.

Which doesn’t mean that every potential ballet student of color comes from a poor family: accessibility means much more than that. “Actually most ballet companies are filled with people who come from middle-class backgrounds,” Webre pointed out, “so I think in terms of recruiting children of color…scholarshipping is not the only thing…the great training academies [must also be] welcoming places for 7-year-old black [children], and…African-American parents [need] to see those ballet schools as welcoming places…and the industry as a place that would support their [children].”

Ballerina Diana Adams and African-American principle Arthur Mitchell performing “Agon.” Photo: Martha Swope.

Will this industry, in fact, support these future dancers? In another Times article, this one in 2013 as DTH was preparing to come back after the hiatus, Johnson told Kourlas that she was shocked at the small number of black dancers who showed up to audition for the re-emerging company. “ ‘…Dance Theater’s lengthy hiatus might have thwarted the ambitions of young, black ballet dancers. Whether or not their dream was to join Dance Theater, at least the company was a tangible prospect.’ ”

So the opportunities, for anyone, to train matter, a lot, but there also has to be an atmosphere that anyone can see themselves in. It’s why Webre invited Copeland to appear at TWB’s school last year, both as a book event for her memoir, but also because he knew how inspiring she would be for the students. “300 kids were there and there was not a dry eye in the house; they danced for Misty and Misty cried and Misty talked about her story and they cried…she was such…a rock star to them and such an example for them and it’s just so motivating…”

Do I think that, today, the directors of American ballet companies are racist? No. (OK: I should understand that there may be some, but thankfully I don’t know of them.) Do I think many companies remain ethnically unbalanced because of the racist policies and practices many areas of our country have practiced in the past couple of centuries? Absolutely.

How long will it take for this to change? “You can wring your hands over the sad state of affairs,” Burns told the Williams students,” or you can become part of the crusade for continuous change.”

“It’s slow movement, but here I am 15 years later, and my company [will be] 20% African American next year,” Webre told me. “The curtain will go up and there’ll be a really diverse group of people on stage.

“Yes, there’s reason for head-scratching for why it’s taken so long but at the end of the day we are breaking barriers…it’s not as quick as we’d have hoped but it is moving, it is moving, slowly but surely…”

Merde and Toi Toi Toi, Ms. Copeland! We’re all with you!

Since 1989, Janine Parker has been writing about dance for The Boston Phoenix and The Boston Globe. A former dancer, locally she performed with Ballet Theatre of Boston, North Atlantic Ballet, Nicola Hawkins Dance Company and Prometheus Dance. Ms. Parker has been teaching for more than 25 years, and has a long history with Boston Ballet School. She is on the Dance Department faculty of Williams College in Western Massachusetts, where she has lived since 2003.

Tagged: American Ballet Theatre, ballet, Ballet West, Boston-Ballet, CityDance, Janine Parker, Misty Copeland, race

As an update, Misty Copeland was indeed promoted to principal at ABT, the first African-American ballerina in its 75 year history. There’s a lovely interview with her here

http://www.cbsnews.com/live/video/misty-copeland-makes-history-becomes-principal-ballerina/

In addition, I always like to add the legacy of Janet Collins, the African-American ballet dancer who broke the color barrier at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, but since that was and is not now a major ballet company per se, her contribution is often left unmentioned. Read about her life in Night’s Dancer.

Hi Debra!

Isn’t it just great about Copeland’s promotion? I was even more thrilled to see that the New York Times first announced it in one of its “breaking news” banners on the website! Yay!

And thanks for the Collins mention…of course she’s another big part of this legacy.

Sincerely,

Janine