Book Review: Artist Mark Rothko — The Painter as Guru

Biographer Annie Cohen-Solal is perhaps strongest on one thread of Mark Rothko’s narrative: his experience as a Jewish immigrant adapting to — and ultimately succeeding in — American society.

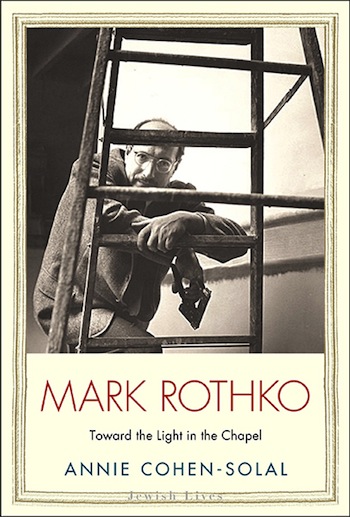

Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel by Annie Cohen-Solal. Yale University Press, Jewish Lives Series, 296 pages, $25.

By Peter Walsh

“Artists are isolated in the United States as if they were living in Paleolithic Europe…. The isolation is unconceivable, crushing, unbroken, damning…. What can fifty do against a hundred and forty million?” True enough in the fall of 1947, when it was published in Horizon, this screed by critic Clement Greenberg was rendered obsolete almost as soon as it hit paper. By the early ’50s, those “fifty” obscure American artists (Greenberg exaggerates the smallness of the number but not by too much) became the leading masters of the contemporary art world: famous men (and a few women) whose images graced the covers of popular magazines and whose art was eagerly acquired by a new generation of curators and collectors, both at home and abroad.

Among those few dozen living at the center of this cultural transformation was a Russian-Jewish immigrant once named Marcus Rotkovitch. Born in 1903 in Czarist Russia to a bourgeois and largely secular Jewish family, Marcus was trained, at an early age, as a Talmudic scholar. Forty years later, two years before Greenberg’s complaint, Marcus became Mark Rothko, by then a respected and soon to be famous and increasingly wealthy American abstract painter. Twenty five years after that, Rothko was dead, a likely suicide, having completed what many have seen as the greatest spiritual apotheosis of American art.

As her subtitle foreshadows, Annie Cohen-Solal’s new biography, Mark Rothko: Towards the Light in the Chapel, arrives at its climax a few years before the artist’s death, in the mid-’60s, with his completion of a suite of large, abstract paintings for Houston’s so-called “Rothko Chapel,” which had been commissioned by two of his greatest patrons and his fellow Jewish immigrants, John and Dominique de Menil. After Rothko’s death, Dominique described this project as “the greatest adventure of his life… as if he were bringing us to the threshold of transcendence.”

Like Dominique de Menial and many, if not most, of Rothko’s admirers, Cohen-Solal seems to see Rothko as a kind of guru in paint, a sage whose soft-edged, abstract compositions in moody colors cultivate metaphysical meditation: these images render words superfluous. Rothko tended to reinforce that ethereal impression. “A picture lives by companionship and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer,” he said. “It dies by the same token.”

All this makes the focus of the artist’s life on the single high point of spirituality in the Rothko Chapel seem both logical and inevitable. Yet Rothko was a complex human being, with a rich, contradictory inner life, much of it now inaccessible. He was also a prolific and searching writer as well as a painter. The man’s career had more ironic twists and turns and blind alleys than straight paths toward the light.

Cohen-Solal herself suggests points at which Marcus’ narrative could have veered off into an alternative existence. The child born as a Rotkovitch could have grown into a Talmudic scholar, or,, if they had stayed in Europe, he and his entire family could have perished in a Russian pogrom or in the Nazi holocaust. Once settled as a new Russian-Jewish immigrant in the Little Odessa section of Portland, Oregon, where the family was known as Rothkowitz, the young Marcus could have gone into one of his family’s businesses, or become a social reformer, or have penned the kind of left-landing political essays that his high school years seemed to predict. Had he succeeded at Yale University instead of dropping out, he might have become a professor and philosopher instead of a painter.

Mark Rothko, No 61 (Rust and Blue), 1953. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.

As is fitting for Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series, of which this volume is a part, Cohen-Solal is perhaps strongest on one thread among the many strands of Rothko’s narrative: his experience as a Jewish immigrant adapting to — and ultimately succeeding in — American society. Nevertheless, key parts of this phase of Rothko’s life took place in the early 20th century and many potential witnesses evidently left behind no first-hand accounts. So the story of young Rotkovitch/Rothkowitz contains many facts but also invites a lot speculation. Quite a few mysteries remain unsolved: why was Marcus sent to a Talmudic school if his parents were secular? Why exactly did the Rotkovitch family decide to leave their native Dvinsk (now Daugavpils, Latvia’s second-largest city) for New York, New Haven, and Portland? Why did the future painter, an academic high-achiever for all of his childhood and adolescence, tank as a student at Yale University and fail to graduate? Why, finally, did Rothko become a painter at all, instead of any number of other destinies, to which his background seemed more sympathetic? Here Rothko’s biographer can suggest, but never pin down, a definitive answer.

Cohen-Solal also does a serviceable job with other important narratives in which Rothko played a leading or supporting role: the slow start and ultimate triumph of American modern art; the creation of a fully abstract approach to painting, with no reference to physical objects in the real world; the creation, among 20th-century Jews, of a vital, central, and influential visual culture where none had previously existed, the cultural rivalries between East and West Coast America and between America and Europe (Rothko divided his time and loyalties among all three regions); and, finally, his life amidst the intense relationships, key friendships, and vigorous rivalries among a few dozen American artists who astonished everyone, most of all themselves, by becoming the leading figures in mid-century world art. These are all riveting stories.

Cohel-Solal was born in Algiers and studied in Paris at the Sorbonne, so English is presumably not her first language. In fact, this book was originally published in French; the copyright page in the Yale edition gives her credit for translating her own prose. The result is acceptable if not especially inspiring in a literary sense. The book also suffers from the sort of editing errors that now hobble even the products of a respected academic publisher. The badly mangled chronology of the 1917 Russian Revolution is presumably a botched abridgment by some under-educated copy editor.

Cohen-Solal’s biographical storyline is also somewhat constricted by the “Jewish Lives” series’ standard format. With notes, bibliography, and index, her book is just 282 pages, compared to the 784 of James E.B. Breslin’s Mark Rothko: A Biography, the only other full-length study of Rothko’s life. The restriction makes an extended consideration of Rothko’s art, as opposed to his life, difficult, and it may also explain the lack of more anecdotal detail about his relationships, especially with his two wives and his young children.

Artist Mark Rothko in 1959. Photo: James Scott.

Rothko’s last few years, from the completion of the Rothko Chapel to his death, apparently by suicide, in 1970, along with the important legal coda to his life that stretched into the ’80s, in which his children successfully sued their father’s gallery for a whole series of despicable practices, seem especially brief here.

Popular mythology has long held that Rothko succumbed to the psychological stresses of unexpected success, wealth, and fame. Gallery owner Sydney Janis explained that Rothko “was a poor boy all his life; he was a poor boy and he just couldn’t get used to riches. That money problem was an albatross around his neck.”

Cohen-Solal seems to attribute Rothko’s suicide more to his declining health from heart disease and attendant depression. After the Chapel, she implies, Rothko’s life work was done, so his continued physical existence amounted to no more than an afterthought in his professional career. Yet she has already described in detail the many conflicts and contradictions of Rothko’s life: his contempt for wealth, capitalism, almost all critics (which he collectively described as “a bunch of parasites feeding on the body of art”), and a corrupt and ignorant art world, all of which he nevertheless relied on for recognition and material success; his contradictory attitudes towards his own Jewish heritage; his need for close relationships and the exacting moral and aesthetic standards that often seemed to sabotage equanimity (‘We always got along best when his life was in shambles,” said his close friend, the painter Robert Motherwell. “And then he was a marvelous friend.”); a deep spirituality that was in conflict with his competitive personality, a tension complicated by his desire to reach the sublime and ineffable through the physical media of paint and canvas. And then there is what curator Katherine Kuh describes as Rothko’s absorption with “the fragile relationship between ethics and art.” Finally, though Rothko complained for years about his lack of recognition, Cohen-Solal shows that he received plenty of praise from quite early on in his career.

Could Rothko’s final decline have been a turning point that might have led the artist in a new direction? At the close of her narrative, Cohen-Solal quotes Motherwell describing the enactment of a final, public ritual of “totemic power” in Rothko’s studio. It appears to have been an attempt to keep sinister, unknown powers at bay. The implication is that the exorcism failed. But in this book the dark period at the end of Rothko’s career is left as yet another unexplored mystery in a rich and enigmatic life.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: Annie Cohen-Solal, Jewish Lives Series, Mark Rothko, Toward the Light in the Chapel

Peter, how did it come to pass that Rothko, born, as you write, “in 1903 in Czarist Russia to a bourgeois and largely secular Jewish family” wound up “trained, at an early age, as a Talmudic scholar. ”

Can you see my difficulty?

Secular and “Talmudic scholar” are opposites.

Not really, Secularization is by no means incompatible with being a scholar of religious belief and tradition. There are many such secular scholars, including many if not most professors of religion, religious history, and religious philosophy teaching in American universities. Among scholars of Judaism and Christianity, here is, in fact, somewhat of a spllt between those who write and lecture on religion from a secular perspective and those who write and teach the same subjects as some sort of believer.

No one knows, however, why the young Rothko was given Talmudic training. Cohen-Solal speculates that Marcus’s father had a heightened sense of Jewish identity as a result of the increasingly severe Russian pogroms of the earlth 20th century. It may just have been because the local Talmudic school provided the best training for a gifted Jewish boy in that time and place, the same way some non-Catholic parents send their children to parochial schools as an alternative to poorly performing public schools or some non-Catholic college students choose to attend Boston College, Washington University in Saint Louis, or some other well-respected Jesuit university. There is no evidence, however, that Rothko’s family became any more religious either before or after Marcus’s Talmudic education, which ended when the family moved to America.