Book Review: Oliver Sacks’ “On The Move” — A Mix of the Distant and the Intimate

Oliver Sacks’ On the Move is an absorbing, idiosyncratic, often moving memoir.

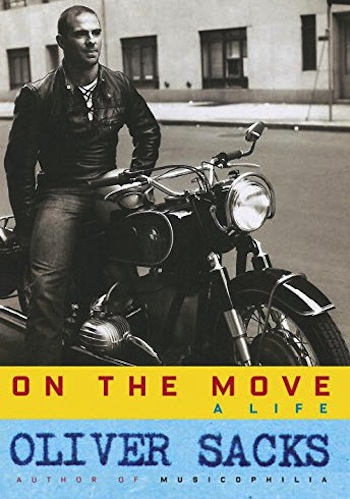

On the Move: A Life, by Oliver Sacks. Knopf, 416 pages, $27.95.

by Helen Epstein

It’s unusual and disconcerting to be reviewing the book of an author who has announced his impending death, on the Op-Ed page of the New York Times no less. I spent some time examining his photographs. The front cover of On the Move shows a virile young man in a black leather jacket, astride his motorcycle in Greenwich Village of 1961; the back, a gray, distinguished but robust-looking elder, writing in a notebook on a bench atop Machu Picchu in 2006. On the Move explores the years that transformed a confused, drug-addicted drifter into a world-renowned neurologist and author.

This absorbing, idiosyncratic, often moving memoir includes family letters, entries from journals Sacks has kept since the age of 14, and unpublished essays that paint Sacks’ career as a series of escapes from multiple rejections and failures in love and work, beginning at Oxford. After his lackluster undergraduate years, his parents sent him to a kibbutz (a common Jewish “cure” for troubled, indecisive youths) to get his act together. After he decides to serve in the Canadian military, his superior urges him to reconsider. Determined to make a career as a research scientist, he’s told by his boss, “Sacks, you are a menace in the lab. Why don’t you go and see patients — you’ll do less harm.” At 40, after years of writing for the drawer, he finally achieves success with the publication of Awakenings (title inspired by Ibsen’s When We Dead Awaken). Eventually he goes on to write twelve well-received books of literary non-fiction. After 35 (unexplained) years of celibacy, he finds a life partner.

Sacks’ life story begs for some discussion of his childhood, but though he has spent 50 years in psychoanalysis he chooses not to share his insights in this book. He has described his parochial Anglo-Jewish parents, his large, education-driven family of origin, and the trauma of being sent away from home as a child to avoid wartime bombings in his first memoir, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood. In On the Move he only refers to them in passing.

For those who have not read Uncle Tungsten, it’s important to know that Oliver was born in London in 1933, the youngest of four brothers. His parents were physicians (his father a GP; his mother, a surgeon and anatomist). His two oldest brothers and three first cousins also became doctors. Both men and women on both sides of his family had distinguished careers in the UK, America, and Israel; one of his aunts founded and ran the first girls’ high school in Jerusalem; the eloquent Israeli diplomat Abba Eban was a cousin. In 1939, the second world war began and children in London were sent to the countryside to escape the expected Nazi bombings. Six-year-old Oliver and eleven-year-old brother Michael were evacuated to a boarding school called Braefield where for 18 months both were malnourished and repeatedly and brutally beaten by a “vicious and sadistic” headmaster. After they returned to London, Michael went on to another abusive boarding school where, Sacks writes, his “first psychosis developed.” He does not comment on how the experience affected him.

In Uncle Tungsten, there’s a passage that helped me get a handle on Sacks’ often frustrating, almost eerie self-detached style, which is punctuated by abrupt revelations of intimate information: “It was at this time that I set up my own lab in the house, and closed the doors, closed my ears against Michael’s madness…I had to create my own world of science so that I would not be swept into the chaos, the madness, the seduction, of his.” By the time the two elder brothers finished medical school and Oliver was 12, Michael had been diagnosed schizophrenic.

On the Move begins six years later. After a few pages about his motorcycle and a trip to Norway, Sacks makes the first of a series of abrupt and painful disclosures. It’s the summer of 1951. He has just turned 18, will enter Oxford in a few weeks, and his father, described much later by the Chief Rabbi of England as “one of the 36 Just Men,” decides it’s time for a father-son talk.

“You don’t seem to have many girlfriends,” Samuel Sacks begins. Oliver says that he prefers boys, but hasn’t acted on it yet, and doesn’t want his mother to know: “She won’t be able to take it.”

Sacks immediately informs his wife and, in Oliver’s account, the next morning she tells her son, “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.” Then she stops speaking to him for a few days, and when she resumes, never mentions the subject again.

The author summarizes the incident and his own feelings about it in one stiffly written page. “My mother, so open and supportive in most ways, was harsh and inflexible in this area. A Bible reader, like my father, she loved the Psalms and the Song of Solomon but was haunted by the terrible verses in Leviticus: ‘Thou shall not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination’…..But her words haunted me for much of my life and played a major part in inhibiting and injecting with guilt what should have been a free and joyous expression of sexuality.”

While Sacks maintained a close correspondence with his parents until they died (portions of On the Move rely on the 8000-word letters he wrote to them), he left England for North America after completing medical school in 1960 and, except for visits, never lived there again. The careful reader learns only in scattered bits and pieces what his parents, his two older brothers, and his relationship with them all were like.

Sacks is more explicit and descriptive about Oxford, his teachers and classmates, and first forays into love. His first – American poet and Rhodes scholar Richard Selig – is heterosexual and, after Sacks declares himself, gently offers platonic love in return: “Our friendship continued, made easier now by my relinquishing certain painful and hopeless longings.” But when, soon after this, Selig is diagnosed with cancer, tells Sacks he has no more than two years to live, and never speaks to him again, the author shares no reaction with the reader. Nor does he offer much comment on his loss of virginity in Amsterdam (which today would be called rape), so drunk that when he wakes up in a stranger’s bed he has no recollection of what exactly happened. At 27, he’s surprised when a lover with whom he has had a year-long relationship is dismayed when Sacks informs him (by mail) that he has decided to leave the UK. Sacks’ descriptions of emotional involvements have an affectless quality. I kept thinking about his experience in boarding school and his time at home with his brother Michael and his sentence about setting up his lab and closing the doors.

He is more open to discussion of his professional odyssey, describing various teachers, and waxing lyrical about his travels, motorcycling, and weight-lifting. He began lifting at the Jewish sports club Maccabi while still a medical student in London in the 1950s. He flourished at California’s Muscle Beach where he lifted 600 pounds, and continued the sport in New York, where he combined his athletic activities with drug addiction. He seems to have tried a wide variety of drugs over a very long period of time and stopped only when he started working with his second psychoanalyst, Dr. Leonard Shengold, in 1966.

About psychotherapy, Sacks says only, “I think it saved my life many times over…We maintain the proprieties – he is always ‘Dr. Shengold’ and I am always ‘Dr. Sacks’ – but it is because the proprieties are there that there can be such freedom of communication. And this is something I also feel with my own patients. They can tell me things, and I can ask things, which would be impossible in ordinary social intercourse. Above all, Dr. Shengold has taught me about paying attention, listening to what lies beyond consciousness or words.”

I find Sacks’ detached analytical style far better suited to case studies than to memoir. He has written many more of these than Sigmund Freud, contextualizing them with more scientific data than was available to his predecessor, earning professional accolades and a devoted readership. But there has also been criticism from colleagues and advocates for the disabled. On the Move explores the stories behind the stories and the objections of the skeptics in a way I found consistent with the rest of Sacks’ narrative: disarmingly candid but perplexingly short on description, characterization, and feeling.

His professional writing began with a book on migraine headaches, drawn from his work in the mid-1960s at a headache clinic in the Bronx. He wrote it in defiance of his supervisor, most of it in a manic nine days, and it was published in 1970. Sacks writes that after it came out friends asked why he had published selected chapters under a pseudonym. He alleges that his boss/mentor plagiarized his work and fired him when he learned Sacks was writing a book about migraines. Concurrently, he was working at Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx where he also got into trouble and from which he was also fired. His writing about patients institutionalized for decades with “sleepy sickness” captured the public imagination. He returned to London to work on it and read portions every evening to his mother, who served as his closest editor. She would die unexpectedly before the book was published in 1973 as Awakenings, missing out on her son’s belated honor in his own country when the volume inspired a documentary a year later.

Author Oliver Sacks — his detached, analytical style is far better suited to case studies than to memoir. Photo: Charles Cohen.

Despite that success, Sacks was, for quite a while, a physician without a place of work. When an Oxford student sought him out in 1976 for an internship, the neurologist wrote back, “My delay in replying is because I don’t know what to reply. But here, roughly, is my situation. I don’t have a department. I am not in a Department. I am a gypsy and survive – rather marginally and precariously – on odd jobs here and there.”

Both the life and the memoir become better as the neurologist ages. Eventually, Sacks’ expansive literary success –- publishing regularly in the New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, his books translated into 25 languages, one made into a play by Harold Pinter, another an opera by Michael Nyman – ends his freelance neurological consulting and results in permanent appointments, first as a professor at Columbia University and then New York University. His books introduce the general reader to a neurological world they might otherwise not know: they include A Leg to Stand On, An Anthropologist on Mars, Hallucinations, The Island of the Colorblind, Musicophilia, and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

After his 75th birthday in 2008, Sacks writes toward the end of On the Move that he met “someone I liked.” He describes his life with writer Billy Hayes as “a tranquil, many-dimensional sharing of lives – a great and unexpected gift in my old age, after a lifetime of keeping at a distance.”

Reading this strange mix of distant and intimate writing, I began to reflect on the importance of biographers. One day, someone will write a comprehensive biography of Sacks and try to answer some of the many questions that the author so tantalizing raises about himself and leaves unanswered.

Helen Epstein is the author of six books of non-fiction including Children of the Holocaust, Where She Came From: A Daughter’s Search for her Mother’s History and the biography of Joe Papp. She co-founder of Plunkett Lake eBooks of Non-Fiction.

.