Film Interview: Rory Kennedy defends “Last Days in Vietnam”

Not everybody loves the documentary Last Days in Vietnam. Director Rory Kennedy responds to some of the criticism.

A scene from the Oscar-nominated documentary “Last Days in Vietnam.”

By Peter Keough

I first saw Rory Kennedy at the 1999 Newport Film Festival (an event now sadly defunct) when she accepted the Jury Award for best documentary for her first feature length documentary, America Hollow. It is an impressive first effort, a detailed and empathetic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men–like immersion into the daily rigors and challenges of a poor but proud Appalachian family.

Since then she has made about a dozen more documentaries, most recently Last Days in Vietnam about the feckless American evacuation from Saigon in 1975. Several critics groups named it the best documentary of the year and it received an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary film (it lost to Laura Poitras’s Citizenfour).

Not everybody loves the movie. That includes Arts Fuse film critic Gerald Peary. In his September 26 review he called it “a flag-waving whitewash of the war in Vietnam.” He compares Kennedy’s Last Days to a documentary about the German retreat from Russia in World War II that doesn’t mention Hitler and the Holocaust.

“Contextualizing is everything,” he writes. “And that’s true also of Last Days in Vietnam, where the odious things we did there weigh down the ostensible heroics shown in our exiting the country.”

Last Days in Vietnam became available on DVD and Blu-ray on April 28, as well as for online viewing here.

I had the opportunity to interview Kennedy last month when she was in Boston for a screening of Last Days at the Kennedy Library. I posed some of Peary’s objections to her, and asked a few questions of my own.

Arts Fuse: Why do you think the film has made such an impact?

Rory Kennedy: This was a story that I felt people didn’t know that was a significant chapter in our nation’s history. Certainly in the history of the Vietnamese. I felt the Vietnamese deserve for us to know this story. We have the responsibility to know the story if for nothing else for their sake. And there are lessons we can learn from this story as we struggle to get out of Iraq.

AF: You were only six when these events occurred. Do you have any memories of that period?

Kennedy: I have some vague recollection of it. I think from a very young age I had an appreciation of Vietnam and that my father [Robert Kennedy, who was assassinated on June 6, 1968, six months before Rory Kennedy was born] really ran his first campaign on getting us out of Vietnam. So it’s more of a general interest in Vietnam over the years rather than a specific recollection of a moment in history.

AF: You didn’t initiate the project, but were asked to do it for PBS’s American Experience. Why did you accept it?

Kennedy: Yes, for [PBS Executive Producer] Mark Samels. My hesitation was that there was that since so much had already been done on Vietnam in terms of coverage and documentaries, frankly, I didn’t know if I could add anything new. But then as I got into it I was blown away by the story itself and how little I knew about it. Now in sharing it over the course of the last year I would that that is also the overwhelming and dominant response of audiences, which is — I can’t believe we didn’t know about this story.

AF: Is that because most viewers were not even born when the events took place?

Kennedy: It’s not just a phenomenon with young people, which is certainly it is because they’re hardly even studying it in school, a fact that is upsetting and disturbing. But also with people of the generation that experienced it first-hand. They know about the helicopter on the roof and they might know the chaos. But understanding what happened, the role of the ambassador, that there were these Americans trying to do the right thing, what Kissinger was doing in Washington the decisions that were being made there. The information that they were operating on, much of which was inaccurate. That there were marines that were left behind on the top of the embassy when they cut off the evacuation. These are story points that people don’t know.

Producer/director Rory Kennedy — “Films really can have an impact.”

AF: Did you find Kissinger a challenging interview?

Kennedy: He was challenging to get. I asked a number of times before he said yes. When he did he did so reluctantly and said he’d give me 20 minutes or so. Ultimately we sat down for over an hour. When I interviewed him he was 89 years old and he had minute-by-minute recollection of the events that took place during that last 24 hours. It was helpful to have that knowledge base and that point of view. Comparing what he said to the consequences for the people who were on the front lines. And also the lack of correct information which informed some bad decisions.

AF: Have you included any of the unused Kissinger material as an extra on the DVD release?

Kennedy: No, I haven’t.

AF: It would seem to have been a good opportunity to give him the same kind of grilling as Errol Morris gave to McNamara [in 2003’s Fog of War] and Rumsfeld [in 2013’s The Unknown Known].

Kennedy: Yeah. I thought of doing a more in-depth interview with him but he was resistant to the idea. But anyway, that’s another story.

AF: Though the response to the film has been overwhelmingly positive, it has received some criticism. Some have said it lacks sufficient historical context, that it implies that Americans were always good guys and ignores the checkered past.

Kennedy: Listen, I feel like the film takes an unflinching look at the larger story, which is that we abandoned the Vietnamese. And there are people in our film like Dam Pham whom we promised we’d get out and who ended up spending 13 years in a reeducation camp. There are people in our film like [U.S. Army Captain] Stu Harrington who says this is the Vietnam War in a nutshell – promises made, promises broken and us abandoning our allies. We’re showing the abandonment of those people by the US government as seen in the experience of the handful of people who did the right thing. I think is an important story and a relevant story.

There are a lot of people who come to this moment in history with a lot of very strong feelings, which I completely understand. There are many films that could be made about those last 24 hours and many other ways to approach. There are many films that could be made about the Vietnam War in general. I chose to tell a very particular story which I think has value and clearly other people do, too. It’s not meant to tell the history of the Vietnam War or the history of American policy. To expect it to tell everything is unrealistic.

There are people who approach this and they go off on a very particular storyline that they want told. If you look at some of the criticism, it’s generally not what’s in the film, it’s all the things that we don’t do. And that happens all the time as a documentary filmmaker. You understand that people are going to come to it with their own sense of politics and their own agenda. You can’t fit everything into the film and if you try to fit everything into the film it’s a disaster. It doesn’t work.

AF: Do you think those who see the film will be motivated to learn more about the broader context?

Kennedy: Particularly for young people, they see this film and it kind of draws them in like a thriller. It has those narrative elements. And then they become curious and want to learn more about Vietnam. And that’s fantastic. It’s very satisfying to me.

AF: In this election year…

Kennedy: Election year. If only. It’s an election 18 months’

AF: …in this endless Presidential campaign cycle do you think Last Days might have an impact on the foreign policy discussions?

Kennedy: We just showed the film on Capitol Hill and to a number of legislators and policy makers. They see in the film the implications of being in these wars and what happens to the people left behind. What is our obligation to these people? Particularly those in Iraq and Afghanistan who worked for Americans and are vulnerable when we leave. It’s hard to watch this film and not see that obligation and responsibility.

It raises important questions about what happens when you take on Isis and become more involved in that conflict. It’s like Colin Powell said, if you break it you fix it, and if you fix it, what are the long term obligations? I think ultimately the film is a reminder of the human cost of war.

AF: Will you be involved in the election?

Kennedy: I support Hillary Clinton and I will support her along the way. I won’t be working full time on it but I’m sure I’ll be involved in some fundraisers and some speaking engagements on her behalf. I’d love for her to get elected.

AF: As a Kennedy, did you ever consider running for office or have you always wanted to be a filmmaker?

Kennedy: I really appreciate people who pursue political office. But I really love making documentaries and I believe they help people understand these issues. Films about historical events told from the perspective of the people involved are meaningful and have value and can contribute to the debate and ultimately influence the direction we go in as a country. Documentaries don’t necessarily change the world but they can make a contribution to people’s understanding of it.

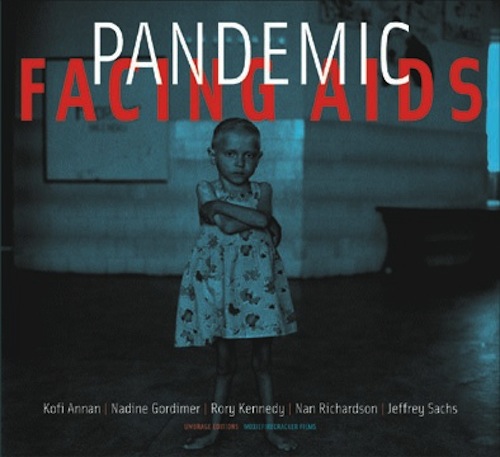

Sometimes it’s hard to track the impact of a film. But just two or three days ago we were in Utah doing screenings of the film and this Vietnamese woman came up to me and said this film changed her life. She said, I don’t think you have any idea of the impact this is having on the Vietnamese community and what means to us. I made another film about Aids [the 2003 documentary Pandemic: Facing Aids] when Senator Pat Leahy came up to me and said I’m putting an extra $25 million in the budget because of this film. Then you see a film like An Inconvenient Truth (2006) and I think if you ask people what they associate with Al Gore won’t be that he was Vice President but that he made this film.

Films really can have an impact. I love making them and that’s the path I’m on.

AF: How did you get started on that path?

Kennedy: I had never taken a film class. I wrote my final paper in college about pregnant women trying to get drug and alcohol treatment. It was at the time when there were a lot of stories in the press about crack mothers having crack babies. It turns out that the vast majority of them statistically nine out of ten tried to get treatment and were denied care because they were pregnant. But none of these articles were saying that. They were saying that crack mothers didn’t care about their babies and they should be thrown in jail.

I was finding a very different story and I thought these women should be able to go to Congress and tell their stories and we should get treatment for them And since I couldn’t bring those women to Congress I can bring a camera to their living-rooms and make a film about them and bring that to Congress.

And that’s what I did. It was seeing a problem and using a film as a solution. At the time I didn’t want to make documentaries for a living. But then I really enjoyed that process and felt like it could make a difference and I have doing so ever since.

Peter Keough, currently a contributor to The Boston Globe, had been the film editor of The Boston Phoenix from 1989 until its demise in March. He edited Kathryn Bigelow Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2013) and is now editing a book on children and movies for Candlewick Press.

Tagged: documentary, PBS, Peter Keough, Rory Kennedy, The Last Days in Vietnam

Rory Kennedy made an insidious right-wing film about the war in Vietnam. I stick with the objections I made to her disturbing documentary: https://artsfuse.org/115107/fuse-film-review-beware-of-the-last-days-of-vietnam-a-neo-con-whitewash-of-the-war/

As for the interview, this seems flatly disingenuous: “.. the film takes an unflinching look at the larger story, which is that we abandoned the Vietnamese. And there are people in our film like Dam Pham whom we promised we’d get out and who ended up spending 13 years in a reeducation camp.” Dam Pham may have been in the film, but we never see him in the re-education camp (unless I slept through that part). Nor do we see what happens to anyone left behind.

The film leaves us with the impression only about 400 people couldn’t be airlifted out … but those are 400 of the thousands who were desperate to leave. Nor does the film give any idea of the numerous atrocities visted on the Vietnamese people by the US, which generated hatred for the collaborators–I’m sure there were French under the Vichy Regime who wanted to get out with the Germans as well. It’s a completely one-sided tale: the US military and secondarily, its Vietnamese allies–allies who didn’t always have a choice.