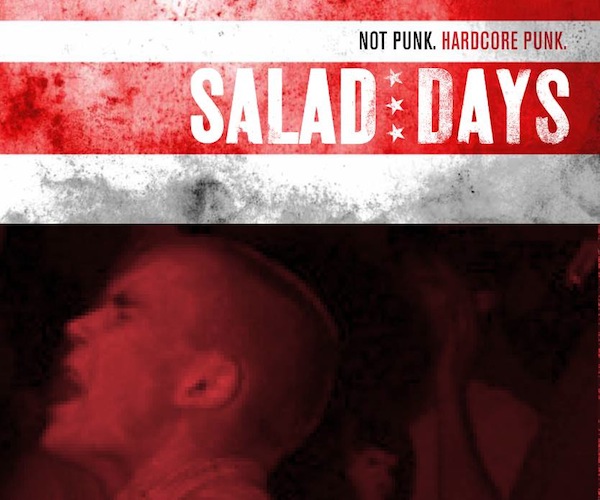

Film Review: “Salad Days: The Birth of Hardcore Punk in the Nation’s Capital”

When no-one was looking, Ian MacKaye and a group of young people like him created one of American alternative music’s most important and unique scenes.

Salad Days: The Birth of Hardcore Punk in the Nation’s Capital, directed by Scott Crawford.

By Adam Ellsworth

“The thing about Washington [D.C.],” hardcore icon Ian MacKaye says at the beginning of the new documentary Salad Days: The Birth of Hardcore Punk in the Nation’s Capital, “is it’s a petri dish for great ideas. They may not be sustainable, but you can always grow something here because no-one’s looking.”

When no-one was looking, MacKaye and a group of young people like him created one of American alternative music’s most important and unique scenes. Directed by Scott Crawford, Salad Days (which screened at the Somerville Theatre last Friday and was presented by Rock Shop) uses new interviews and rare, sometimes grainy, concert footage to tell the story of music generated by that time and place. It’s an excellent, and certainly complete, film that touches on all the bases that made D.C. hardcore in the ‘80s and early ‘90s the revolution that it was.

“It wasn’t about sex, drugs, and rock and roll,” D.C. musician Bobby Sullivan says of the scene in the film.

It surely wasn’t. Maybe for some scenesters and musicians it was, and Salad Days gives those individuals a voice too, but D.C. will always be associated with straight edge (no drugs, alcohol, or sex for sex sake) and, starting in the second half of the decade, a righteous social conscience. That and the music itself, made by the likes of Bad Brains, Minor Threat, Void, Beefeater, Rites of Spring, Fugazi, and more.

Bad Brains, a group of reggae-loving Rastafarian punks, were the first of the city’s legendary bands and their influence was immense. Minor Threat, however, were the scene’s Beatles. Their songs were fast, furious, and catchy as hell. MacKaye was their singer and provided the template for straight edge through the group’s songs like “Straight Edge” and “In My Eyes.” Perhaps more important, MacKaye and the band’s drummer Jeff Nelson founded Dischord Records to release their music as well as the music of other hardcore bands in the city.

It’s no surprise then that MacKaye (who also featured in the bands Teen Idles, Embrace, and Fugazi) and Nelson are two of the more recurring voices in the film, but they aren’t the only ones. Henry Rollins, who is most famous for fronting L.A. hardcore pioneers Black Flag but grew up in D.C. and sung in the band S.O.A., provides great insight into the earliest days of the scene and the danger that young punks in the city faced in the late 1970s.

“Just your appearance has questioned their masculinity, and now they have to confront you,” he says of altercations he and his friends had with D.C.’s meathead population.

As the ‘80s moved on and the “kids” began to get older, the music started to evolve, as did the social and political involvement of the scene. The activist group Positive Force began holding fundraiser shows, and the group’s founder, Mark Andersen, is interviewed throughout the film. Anderson speaks movingly about 1985’s “Revolution Summer,” which occurred when the new political awareness merged with the less volatile sounds known as “post-hardcore” or “emocore.” His presence illustrates the point that like any good scene, the D.C. scene was as much about community as it was about music.

Thankfully, Salad Days is not just a bunch of D.C. partisans blowing smoke about how great they all were. For one thing, “outsiders” J Mascis and Thurston Moore are interviewed to give their perspective, which is complementary, but at least unbiased. Also, the scene is called out for being something a “boys club,” especially in the early days, by the women who were there, including singer Monica Richards. Finally, the filmmakers give time to bands like Black Market Baby that were not at all straight edge, as well as groups like Kingface that were less interested in the social/political aspects of the mid-‘80s iteration of the scene.

So it wasn’t always one big happy family. But the music is undeniable. Salad Days draws to a close with the rise of Fugazi, fronted by MacKaye and Guy Picciotto from Rites of Spring. The group’s success opened doors for other D.C. bands and ensured that the music of the scene would spread well beyond the 68 square miles that make up the district.

And spread it did. By the early ‘90s, “alternative” and “punk” would be mainstream, but Fugazi and the rest of the D.C. bands never jumped on the gravy train. Maybe they could have though. There is a funny moment near the end of the film when MacKaye tells the story of Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegün coming to a Fugazi show and telling the band that he’ll do a deal with them like he did “with Mick.” Yes, Ertegün looked at Fugazi and saw the Rolling Stones. That might not have turned out to be the best business move, but there’s no denying the man always had taste.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has a MS in Journalism from Boston University and a BA in Literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: Adam Ellsworth, Alec MacKaye, Dave Grohl, Henry Rollins, Ian MacKaye, John Stabb, documentary, hardcore punk