Book Review: Using Words as Weapons — Alain Mabanckou’s Tribute to James Baldwin

Like James Baldwin, Alain Mabanckou is striving to see beyond comforting or righteous notions and, in our day and age, grasp a world full of movement, migration, diversity, and unexpected mixtures.

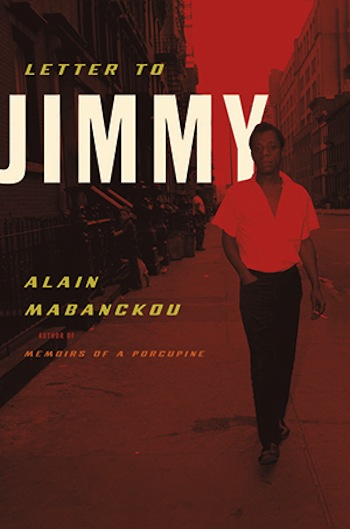

Letter to Jimmy (On the Twentieth Anniversary of Your Death) by Alain Mabanckou, translated from the French by Sara Meli Ansari. Soft Skull Press, 168 pp., $14.95.

By John Taylor

Letter to Jimmy is a well-documented tribute to James Baldwin (1924-1987) by the Francophone novelist Alain Mabanckou (b. 1966). Underlying this homage of a younger writer to a mentor whom he never met is that their literary and intellectual, indeed spiritual, encounter could almost be called inevitable. Roughly speaking, Mabanckou’s life is symmetrical to that of the American novelist and essayist. And this bio-geographical configuration increases the engaging qualities of the Letter.

Born in Harlem, Baldwin settled in France at the age of twenty-four and thereafter spent most of his life there, although he also lived in Turkey and Switzerland. As to Mabanckou, originally from the Republic of the Congo, he moved to France at the age of twenty-two to continue his law studies and then, after writing his first (award-winning) books, moved to the United States, where he has taught French literature since 2002, first at the University of Michigan and now at UCLA.

His Letter opens on the Santa Monica State Beach, where he regularly spots a gray-bearded beggar who reminds him of a Baldwin character. “Never has a stranger so fully captured my imagination,” Mabanckou explains (to Baldwin), “prompting me to trail him, as if I expected him to reveal the key to the mysteries that confront me when I read your work.”

Living abroad—a double expatriation in Mabanckou’s case—is naturally a topic raised in this book that is also a streamlined biography of the American writer. Mabanckou reminds Baldwin of his own decision to leave the United States in 1948: “Your illustrious colleagues who preceded you in France emphasize their feelings of being writers in their own right, instead of being people entirely devoid of rights. In France, they are not considered black: they are artists, first and foremost, writers who capture the attention of the intellectual scene in their adopted country.”

Citing a New York Times article from 1977, Mabanckou adds: “Later you will admit that you wanted to live in a place where you could write without the feeling of being choked. France became the place where you blossomed, where you truly began to fight with the weapons at your disposal that no one could take away: words.”

Also symmetrical or, rather, parallel is the fact that Baldwin’s political viewpoints stimulated controversy in the United States, whereas Mabanckou’s stands on current French issues have likewise sparked debates about immigration, integration, and communitarianism.

In his Letter, he notably informs Baldwin about the anti-Semitic torture and murder of the twenty-three-year-old Ilan Halimi in January 2006 by the “Gang of the Barbarians” from the Parisian suburb of Bagneux. The gang was led by Youssouf Fofana, born in France of parents originally from the Ivory Coast.

This event triggered vast community reactions and, beyond the protest and the disgust, generated discussions about communitarianism as a challenge to ways in which French society is ideally conceived. The same debates have emerged in France ever since the terrorist attack at Charlie Hebdo and the murder of four Jewish customers at the Kosher grocery store in Vincennes—though Mabanckou of course does not deal with this topic in a book originally published in 2007.

Thinking about such events must take into account the fundamental French notion of laïcité, so difficult for Anglo-Americans to comprehend, whereby in the “public sphere” a human being is (legally) considered to be not a member of any racial, religious or other “community” but rather a “citizen” living under the banner of a theoretical equality.

Beyond such constitutional ideals, however, Mabanckou focuses on the protest expressed at these and other unjust, racist, or gruesome acts. He asks whether the outrage, however well meaning, should be generated by community sentiment or rather—this is his position—by one’s “sense of humanity” that has sustained the “injury.”

Such questions fuel the deeper theme running through the Letter: a writer’s independence and, more generally, a human being’s independence vis-à-vis the “communities” from which he originates or is wittingly or unwittingly attached. Mabanckou has been inspired by Baldwin’s own individualist and yet by no means politically disengaged posture. “I hold in high esteem the independence of the writer, Jimmy,” he declares, “and am weary of ‘herd-mentality literature.’ A writer should always share his own vision of the human condition, even if it runs counter to commonly held, moralizing beliefs.”

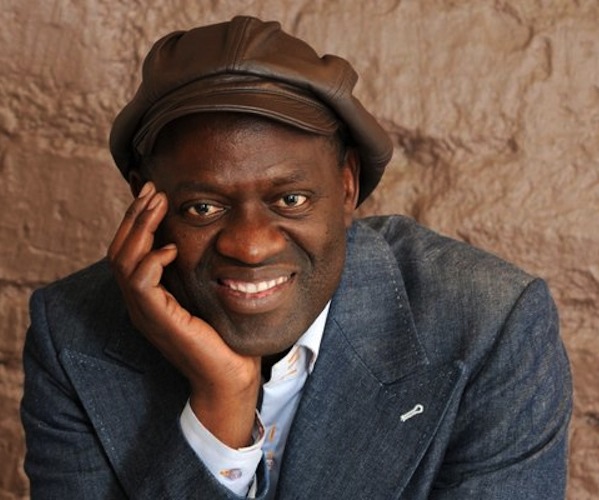

Novelist, journalist, poet, and academic Alain Mabanckou — inspired by Baldwin, he is seeking a lucid, literarily legitimate and intellectually rigorous approach to African tragedies as well as to immigrant problems in France.

Like Baldwin’s own stance during the American civil rights movement as it evolved during the 1950s and 1960s, like his rejection of systematic anti-White rhetoric (notably that of the Black Muslims), and like his dismissal of Afro-American “protest novels” written in the wake of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as “both badly written and wildly improbable,” Mabanckou is also seeking a lucid, literarily legitimate and intellectually rigorous approach to African tragedies as well as to immigrant problems in France. His remark about “herd-mentality” continues by questioning “a variety of African literature known as “child soldier” literature—or as “Rwandan genocide” literature, when it was created more in protest than in an effort to truly understand the tragedies.” Such literature, Mabanckou asserts

convinced me definitely that we were not yet free of the vortex of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and that the sentimentality and moralizing current that runs through some of these works does harm to African literature. If we are not careful, an African author will be able to do nothing but await the next disaster on his continent before starting a book in which he will spend more time denouncing than writing. People will loudly remind me of our duty to be politically engaged, to tell the tale of Africa’s woes, to publically accuse those who drag the continent downward. But what is the value of political engagement if it leads to the destruction of the individual? Many hide behind this mask in order to teach us lessons, to impose upon us a vision of the world where there would be the true children of Africa on one side, and, on the other, the ingrates—meaning the latter are considered Europe’s lackeys.

French readers hear in such a passage the echo of André Gide’s famous caveat “it is with good feelings that one produces bad literature.” But Mabanckou reminds us, when he analyzes Giovanni’s Room (1953) in another passage, that Baldwin found a way of dealing with “the collective” all the while avoiding the pitfalls of politically committed literature. This novel about a homosexual relationship, writes Mabanckou, “is heart wrenching, as much for the characters’ anguish as for the beauty of the writing, rendered lively and sensual through its poetic intensity and the strength of its imagery.”

“Rather than mulling over the collective unrest over the black condition,” specifies Mabanckou, “you [Jimmy] explore individual desperation, the hopeless tragedy of a man confronted with solitude and accepting a fate that drives him to self-destruction. In this lies the meaning behind the entire body of your work; understanding the collective through the individual.”

How indeed should “the collective” be viewed in today’s world and especially in France? What roles should “communities” be given in the polis? Should a writer speak up for his “community”? What dangers arise when communities are pitted against one another?

These topics are as timely for us as they were for Baldwin, and even more so in France because of the aforementioned ideals traditionally entertained about society. As to the issues raised by immigration and integration, Mabanckou argues that there are marked differences between the American “black community” and a putative “black community” in France. He points out that Africa is “disparate and divided,” with the culture of one country not necessarily being that of another, thus the sometimes vast and deep differences among African immigrants.

Moreover, adds the author, “the displacement experienced by these [African] countries, in addition to the displacements created by French colonial policies [. . .] create personal histories deeper than any collective history of meeting in the “land of refuge.” Like Baldwin, Mabanckou is striving to see beyond comforting or righteous notions and, in our day and age, grasp a world full of movement, migration, diversity, and unexpected mixtures. It’s the personal history that is essential. “In some respects,” writes Mabanckou,

I would say that the black community in France is an illusion, that it does not exist, for the plain and simple reason that the existence of a community is an intellectual and historical construct. The existence of a so-called black community in France would presuppose a collective awareness of it, and I am referring to an awareness based on reasons beyond skin color, or belonging to the same continent, or to the more defined black diaspora, which, more and more, proclaims its singularity, its “rhizomic identity,” as Édouard Glissant would say. It is through the present, through encounters, that this common identity is woven; sometimes we can even find ourselves surprised by how much it conflicts with the idea of a “primary root” that would lead us all back to a single past.

Like Glissant and other Caribbean writers (Patrick Chamoiseau comes to mind), Mabanckou’s contends that every individual must discover and assume his “rhizomic identity” instead of taking refuge inside a group identity or alongside some “primary root.”

By his adolescence, Baldwin was himself struggling away from several “primary roots,” that is, breaking off from “communities” in an attempt to find and assert his own individuality. He rebelled against them one by one as he came of age as a writer.

Among these communities were Afro-American Harlem (from which he fled to Greenwich Village and then to Paris), the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly Church (at which his stepfather preached and at which he himself began preaching at the age of fourteen, only to break away from religion a few years later), his initial literary heritage (the Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen was one of his junior high school teachers and he would soon thereafter meet his mentor Richard Wright, the fundamental principles of whose fiction he would later brilliantly and trenchantly critique), not to forget heterosexuality, for by his late teens Baldwin realized that he was gay.

As if summing up what Baldwin was ultimately seeking through these escapes and rebellions, David, the main character of Giovanni’s Room, states that “people can’t, unhappily, invent their mooring posts, their lovers and their friends, anymore than they can invent their parents. Life gives these and also takes them away and the great difficulty is to say Yes to life.”

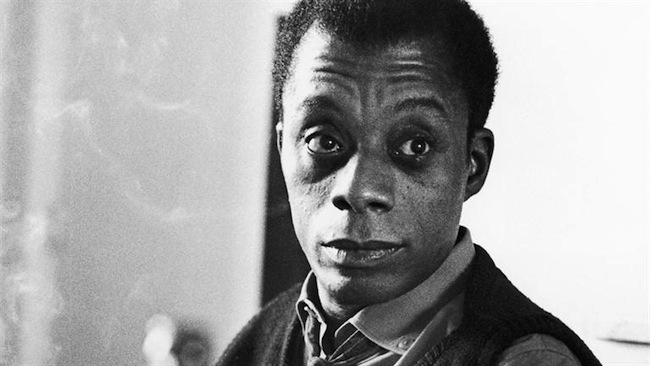

Author James Baldwin — his political viewpoints stimulated controversies in the United States whereas Mabanckou’s stands on current French issues have likewise sparked debates about immigration, integration, and communitarianism.

Throughout much of the Letter, addressing the American novelist with “you” (and with the informal “tu” in the French original), Mabanckou relates how Baldwin arrived fatherless in the world, how he was raised by a courageous mother and a disparaging stepfather (although Baldwin himself retrospectively nuanced certain aspects of this stepfather-son relationship), how he matured as a novelist, how he entered the fray during the Civil Rights Movement, and how he died from cancer in Saint-Paul-de-Vence.

Basing his narrative on Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son (1955) and scholarly works unavailable in French translation, such as James Campbell’s biography Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991) and David Leeming’s James Baldwin: A Biography (1994), Mabanckou provides a vivid outline of Baldwin’s life and recurrent themes.

This aspect of the Letter could be defined as a biographie à la française. French biographers avoid amassing details and reproducing laundry lists. They seek the essence of a life, its synthesis. Mabanckou has done this well, especially for French readers who possess little biographical knowledge of Baldwin. But even for Americans who are more familiar with Baldwin’s life, the letter-narrative vividly traces the admirable scope and originality of his accomplishment.

It nonetheless remains a little disappointing that Mabanckou reveals little about his own novels and his reading of Baldwin not only as essayist but also as a literary craftsman. But one gets the gist. Like Baldwin, he insists on high stylistic and intellectual standards and, while by no means adopting an ivory-tower attitude, underscores the necessity for a writer to maintain the firmest individual vantage point.

“What, after all, does Baldwin teach us if not that desperation, internal agony and ‘the unbearable lightness of being’ haunt all races?,” Mabanckou writes in his conclusion. “From there,” he continues, “the writer must invent—or even reinvent—a universe in which neighborly love is our only salvation, since none of us can hide from the inevitable truth, [in Baldwin’s words]”:

Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. [. . .] Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, the only fact we have.

Born in Des Moines in 1952, John Taylor settled in France in 1977. His most recent translations include books by Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Jacques Dupin, Louis Calaferte, and José-Flore Tappy. Transaction has just issued his A Little Tour through European Poetry, a collection of essays, which follows upon his earlier collections: the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature and Into the Heart of European Poetry. His most recent book of short-prose writings is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press).

Tagged: Alain Mabanckou, James Baldwin, Letter to Jimmy, Sara Meli Ansari, Soft Skull Press, french

Anything written by Mabanckou is an original, subversive delight. I particularly loved – and often howled over – the novel Black Bazar. Perhaps it will be out in translation soon.