Book Review: “Selected Letters of Norman Mailer” — Many More Pieces of His Mind

It’s refreshing and more than a little nostalgic to see the trials, triumphs, and tribulations of Mailer’s time through his own combative eyes, before writers were marginalized as influential public figures.

Selected Letters of Norman Mailer Edited by J. Michael Lennon. Random House, 896 pages, $40.

By Matt Hanson

For a man who claimed to hate letter writing, Norman Mailer generated a lot of them. The ever-industrious author of over thirty books left behind approximately 45,000 letters in his personal archive, significantly more than any of his literary contemporaries. What emerges from reading through his correspondence is a Mailer who never ever stopped betting on his odds for greatness — he rarely missed an opportunity to give the world (believers and unbelievers) a piece of his mind.

The new collection’s vital statistics alone are impressive enough. Spanning more than half a century of a very public and rather tumultuous life, this sizeable new edition contains over seven hundred individual, annotated letters, filling over eight hundred pages (less than 2% of the archive). J. Michael Lennon, Mailer’s authorized biographer and literary executor, has done yeoman’s work in compiling Mailer’s enormous correspondence. The editor remarks that, other than the renowned author himself, he is the only other person to have read the entire bundle.

It’s probably not surprising to anyone who knows his writings that Mailer kept up an industrious, Victorian-style commitment to his personal correspondence, often dictating a dozen letters in an afternoon, sometimes reaching up to fifty a day. As the missives show, Mailer never lost his Brooklyn chutzpah and relish for a good brawl, verbal or otherwise. As the years and pages pass, he never misses a chance to hurl another salvo or to opine with aplomb, taking on all comers regarding every subject under the sun. Seemingly everyone who wrote to him for any reason, old pro or budding amateur, got a proper letter back.

The image of an egotistical industrial complex is clear: pacing back and forth like a Hollywood mogul or the general he’d always longed to be, stormin’ Norman would dictate colorful details about his works and days to his secretary and, with that done, head back to the writing desk to get some real prose under his belt. He takes obvious pleasure in recounting his recent, high flying adventures while mixing in earnest digressions into philosophy, politics, literary gossip, writing advice, and family business.

Mailer’s private correspondence, like his novelistic ambition, was large and contains multitudes. Mailer was one of the few American writers who could honestly engage with people from any level of society and not break stride. One minute he’s sharing dirty jokes with an old drinking buddy, the next he’s instructing convicts on Existential philosophy.

The range of his correspondents is impressively democratic. There are political rivals, such as William F. Buckley and Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and cultural figures, including Marlon Brando, Henry Kissinger, and Monica Lewinsky. He’s equally at home schmoozing with literary eminences such as Diana Trilling and Robert Lowell, penning open letters to Fidel Castro, or offering political advice to Bobby Kennedy and Bill Clinton. He goes to all the parties, appears on all the talk shows, constantly protesting and speechifying.

Mailer was not only writing his version of history, but living his own unruly version of the American Dream. In the early sixties we learn that Jack Kennedy spent a day and a half in Hyannis reading Mailer’s controversial Hollywood novel The Deer Park. Rumor has it that the prince of Camelot approved. The Mailers accepted the invitation to Truman Capote’s infamous black and white ball and Norman came dressed in a raincoat, purposely being voted worst dressed man of the night. Norris, his sixth and final wife, had dated Governor Bill Clinton back in Arkansas.

All this Zelig-like scene-making amid an enviable social schedule came with a heavy psychic price tag. Even given his knack for productivity, Mailer often laments he doesn’t have enough time to finish the current epic manuscript he’s spent the last decade working on (in the eighties it’s Ancient Evenings, in the nineties it’s Harlot’s Ghost). At several points in his life he puts his entire savings on the line to support various unsuccessful plays and movies. Mailer is always one step ahead of disaster, inevitably over-his-finanical-head with constant projects, numerous ex-wives and a growing brood of children to support. On several occasions he claims, semi-jokingly, that he better make sure the next book is a masterpiece or he’s ruined.

In his later years, the literary advice the professional fight-picker doles out to wannabe writers who seek his blessing is surprisingly moderate. He tells them not to trust the highs and lows of their moods but insists that “one writes from the middle of one’s talent.” This is a surprising statement from someone who wasted a lot of his time loudly and blatantly campaigning for the role of Greatest American Writer, a man who once proclaimed that his ambition was to “create a revolution in the consciousness of our times.”

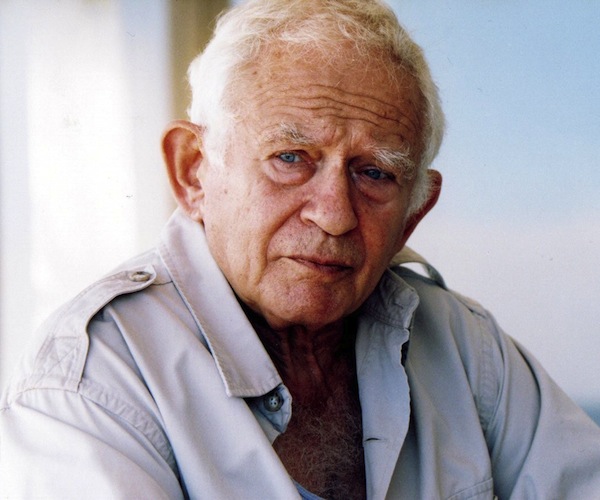

Author Norman Mailer — part of the fun of reading Mailer’s letters is seeing how he adjusts to the world as it changes around him.

You can see the fierce ambition beginning to form in some of his earliest letters to his first wife, Beatrice, during his World War II service in the Philippines. Predictable descriptions of grueling patrols and detailed anecdotes about dead Japs give way to meditations on the apocalyptic nature of technology after hearing that Truman had used the Atomic bomb. Both Mailer and the reader know that he will soon use his letters home as the basis for his first novel, The Naked and the Dead. The young writer is shaken by the carnage, but you can tell he’s also excitedly storing up memories that he can mine for literary use. What we know and he doesn’t is that he will pen a bestselling novel that will also win a Pulitzer Prize — a double whammy that will hang like an albatross around his neck for years afterward.

Part of the fun of reading the letters is seeing how Mailer adjusts to the world as it changes around him. Gore Vidal, a formidable rival and adversary if there ever was one, was right in the one positive thing he ever said about Mailer: he was “interesting because he was interested…” Over the years Mailer continually offered blurbs for small, edgy magazines and defended iconoclasts such as William Burroughs and Salman Rushdie. In 1986, as the elected President of PEN, he incurred the wrath of the festival by inviting Reagan’s Secretary of State George Schultz to speak. Throughout his occasionally inexcusable excesses, from his despicable treatment of his second wife Adele to his quixotic advocacy for the parole of the psychotic criminal-turned-author Jack Henry Abbott, Mailer remained tenacious enough to stay in the game and to keep working through all the uproar.

While he didn’t always hit the prophetic heights he sought and he made quite a few embarrassing public remarks in his efforts to stir up trouble (see his disheveled appearance on The Dick Cavett Show and the hostility-fest of D.A. Pennebaker’s vérité documentary Town Bloody Hall for a start), Mailer managed to stubbornly hang on as a relevant, respected professional novelist long after it was thought hip to be one. It’s refreshing and more than a little nostalgic to see the trials, triumphs, and tribulations of Mailer’s time through his own combative eyes, before writers were marginalized (through their own efforts in some cases) as influential public figures. If nothing else, the volume reminds that there was a time when the American novelist was a cultural force to be reckoned with: there was something was at stake every time a respected writer put pen to paper. Mailer’s letters reinforce the idea that Mailer himself was his most complex creation: the blithely gargantuan demands of his imagination shaped his life was well as his fiction and journalism.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.