Fuse Book Commentary: Found in Translation — Out in the ‘Burbs

Every writer fantasizes about passionate readers. These were as passionate as they come.

By Helen Epstein

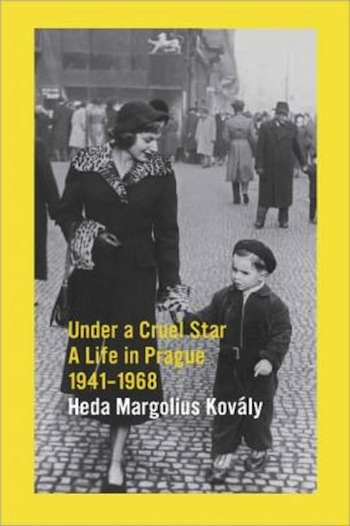

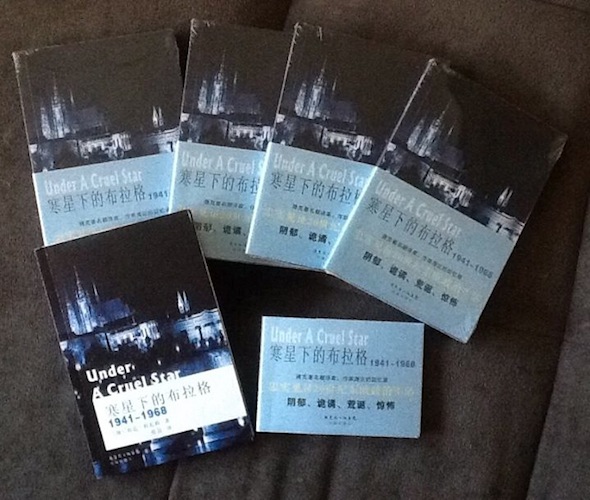

Sometime between snowstorms in Lexington, MA, I received a large package from Flower City Publishing House in Guangzhou, China. It contained 15 copies of the Chinese edition of Heda Kovály’s memoir Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968, an account of her life under Nazism and Stalinism in Czechoslovakia, which I translated from the Czech into the English 30 years ago.

As I shelved the books and wondered who I knew who could read them, I remembered that my historic town — cradle of the American Revolution — is now home to thousands of immigrants, including more than 3000 Chinese. They or their visiting relatives might be interested. I posted on our town listserv and, within an hour, had more demand than I could supply.

Every writer fantasizes about passionate readers. These were as passionate as they come. Even before the snow let up, Sheiling was parked in my driveway. A 60-year-old illustrator, antsy at being confined to reading Chinese editions of the NYTimes and Wall St. Journal online, he was looking for a good book. After 15 years in the U.S. Sheiling says he understands only about 70% of English literary texts; he prefers to read in Chinese. He reminded me of my Czech father, who had a classical education but first encountered English at the age of 44. He was restricted to reading abridged bestsellers in the Reader’s Digest Condensed Books series of the 1950s.

Sheiling was followed by Melanie, a scientist who came to the US to attend graduate school seven years ago. Her English was fluent but she, too, preferred to read in Chinese and was particularly interested in a cultural revolution in a different country on a different continent, She had read Madeleine Albright’s biography and Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being (which had been a best-seller) in China. Could I spare four copies? One for herself and one for each of Lexington’s three senior villages that were filled with literate people who did not read English.

I was thrilled. For years I had been almost as invested in the readership of Heda’s book as I was in my own books. I was born in Prague and my professional life had ignited there during the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. I was a 20-year-old student at Hebrew University then, on my way home to New York from Jerusalem through Europe. My hosts insisted I remain inside, so I mostly did. But I found a typewriter and began tapping out what I saw in the street and heard over the radio. When we finally arrived in Paris, I mailed one copy of what I had written to the NYTimes and the other to the Jerusalem Post. The Post published it and, when I got back to Jerusalem, offered me a job.

I became a reporter, then an author, married, moved to Massachusetts. There, in 1985, a friend introduced me to Heda Margolius Kovály.

Heda was a Czech, petite and blonde, of my mother’s generation. She had survived the Holocaust and the Stalinism of the 1950s by using her wits but, in the presence of men, liked to disguise them under a 1950s Central European version of ditz. When we met, she was working as a reference librarian in Harvard’s International Law Library where her knowledge, experiences, and several languages were prized. She told me that she had written a thriller and had translated into Czech 24 books by authors such as Raymond Chandler, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth.

I wondered aloud if she had ever thought about writing a memoir. She had. It began with her escape, in 1945, during an evacuation from a Nazi labor camp, then hiding in Prague until liberation. She married her first love, Rudolf Margolius, and watched her idealist husband rise within the post-war Czechoslovak Communist government. Stalinism prevailed over idealism and in 1952 he was arrested and tried with 13 other men in the Slansky show trial. He was executed as a traitor, leaving Heda to raise their four-year-old son alone.

A Czech philosopher had translated her story, written his own text and had them published together in 1973. Would I like to read that?

I did. There wasn’t an obvious market for a retranslation of a memoir by an unknown Czech librarian. Less than five per cent of books published annually in America were translations. But I was pregnant, my own writing impulse was dormant, and I felt my old childhood hunger for books about heroines and history.

The late translator Michael Henry Heim, when asked why he didn’t write his own books, retorted that “there are so many wonderful books that need to be translated.…I prefer to work on those books that I already know can change people’s lives.”

This was one of them. I translated alone and then, sitting side by side with Heda at our dining room table. I had a feeling, unlikely as it seemed, that her text would become a classic and it did. We sold 6000 copies from our dining room table, then to major publishing houses in the U.S., UK, France, Holland, Germany, Spain, Japan, Denmark, post-Communist Romania and Czech Republic. But I never thought it would be published in Communist China.

Now here I was, handing a copy of Heda’s story of life under Czech Communism to real-estate agent Fuang, from Taiwan, who realized she would have trouble reading it. Non-Mainland Chinese read traditional Chinese characters, she explained, while Mainland Chinese read simplified characters introduced after the Cultural Revolution. She suggested we donate her copy to our public library. It was well-stocked with books from the Mainland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. But there were never enough good ones.

Finally I talked with Wenjie, a chemist, and her OB/GYN mother who had visited Prague last summer and fell in love with it. Over dried Chinese dates, we discussed history, non-fiction, and memoir. Mom was sure she would finish Heda’s overnight.

I told them I was curious whether Flower City Publishing House had been able to publish Heda’s Life in Prague 1941-1968 in its entirety, or whether the more political parts fell victim to Chinese censors. They and Melanie promised to let me know if they thought anything was missing.

As the snows keep coming, the MBTA keeps breaking down, and some Bostonians are diving out of windows to pass the time, I’m glad to have helped some people keep sane with a good book.

Helen Epstein has published six books of non-fiction.

Tagged: Chinese, Culture Vulture, Heda Kovaly, memoir