Book Review: “Nagasaki”‘s Diptych of Aloneness

The success of this short novel set in Japan lies in the empathy it creates for a pair of ordinary and lonely characters.

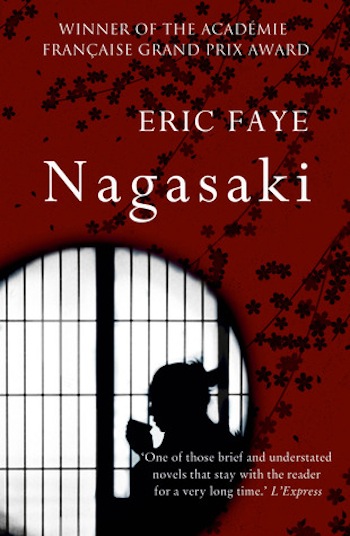

Nagasaki by Éric Faye, Gallic Books, 112 pp., $12.95.

By John Taylor

Éric Faye’s short novel Nagasaki creates an eerie, oddly droll, kind of suspense. The main character and initial narrator, a fifty-six year old Japanese bachelor and meteorologist named Shimura Kobo, suspects that someone has been entering his house while he is away at the weather station making forecasts. The clues are slight, yet troubling enough to make him wish to follow up on them. He sets a trap. One evening, upon returning home from work, he takes out a “stainless-steel [ruler], forty centimeters long,” as he specifies, and re-measures the quantity of fruit juice—“with added vitamins A, C, and E”—left in the carton. The ever precise, anxiety-ridden Shimura Kobo discovers that seven centimeters have disappeared since his previous measurement that morning. “And yet I live alone,” he must admit to himself.

He subsequently equips his kitchen with a webcam that he can operate from his computer at work. And sure enough, one day, as he is talking to two new colleagues, all the while keeping an eye trained on the rectangle in the bottom right-hand corner of his computer screen, he spots a figure

moving about on screen . . . and silhouetted. . . As I carried on talking to the two men next to me, I gradually realized that the person I was dealing with was a woman and, judging by her hairstyle and slight frame, no longer a girl by any stretch of the imagination. . .

The rest of the plot is straightforward: the weatherman calls the police; they arrest the woman; a trial takes place; Shimura Kobo (who has never met her face to face) offers testimony pleading for leniency. After she is released from prison, she writes a letter to him, filling in the details of her life’s story and explaining—this is the un-straightforward fact—how she came to hide out in his house for over a year, including when he was there. Moreover, the very house that she has chosen as a squat has a special relationship to her earlier life, as will be revealed toward the end.

The last half of Nagasaki is in fact narrated by this homeless woman (who had thus found a temporary home), creating a dual narrative structure that has an engaging formal simplicity to it. This book is a diptych of aloneness. The man has a stable job, but he leads a solitary existence without expectations, while the woman’s life was disrupted at the age of eight by the loss of her first family home, which was razed because of a housing project, and, at the age of sixteen, by the accidental death of her parents. She was also cast into seclusion, as well as onto the streets. The respective tonalities of the two diptych panels are not entirely equivalent. The man’s daily routines show some amusing quirkiness, whereas the woman’s itinerary is comparatively solemn.

Author Éric Faye — his short novel won the Grand Prix of the French Academy in 2012.

As she relates her story, most of the details are moving, yet a few—her political commitment, notably, and her involvement with the United Red Army—tend to water down the emotion that the narrative has been distilling all along. The ending—her letter—occasionally distracts the reader from what has become a touching tale of two parallel solitudes. This is not a matter of whether a political dimension, however slight, should be introduced into such fiction, but rather how such details are vectored: outwards towards generalities, as is the case a few times during the woman’s tale, or inwards toward the psychology of the character. I think that Faye definitely intended them to elucidate the woman, and even the man, but I am not sure that all readers will make sense of them this way.

A few asides are also made about Japanese life and the American bombing of Nagasaki—where the story takes place some sixty years later. These brief inserts are by no means uninteresting, especially the incredible anecdote about the man who survived both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. But aren’t these additions journalistic filler, even if they are pronounced by other, minor, characters? I am reminded of Edgar Allan Poe’s remark on the short story (in his 1842 review of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales), namely that “no word” should be written “of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design” of the tale, lest the narrative lose some of its potency.

The success of this novel, which was published in France in 2012 and won the Grand Prix of the French Academy, lies in the emotion that Faye’s two ordinary characters arouse. They are “nobodies,” as the woman calls both herself and her protagonist. The author draws out the discreet features (and wounds) of their modest personalities in the context of a Japan that has emerged since the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A Japan which can seem dehumanized yet which, in the light of this story, is not entirely so. The reader will go back the beginning and reread Pascal Quignard’s epigraph: “It is said that all bamboos of the same stock flower together and die together, now matter how far apart they are planted.” The remark invites one to speculate on what happened next, which is the point.

John Taylor has recently published A Little Tour through European Poetry (Transaction Publishers) and a translation of José-Flore Tappy’s collected poetry, Sheds (Bitter Oleander Press). His most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press). He lives in France.

Tagged: Gallic Books, Nagasaki, french fiction, Éric Faye