Book Review: Émile Zola’s “The Conquest of Plassans” — “Tartuffe” Gone Realpolitik

Entertaining yet incisive, The Conquest of Plassans remains a devastatingly acute reminder that religion and politics make surprisingly compatible bedfellows.

The Conquest of Plassans by Émile Zola. Translated from the French by Helen Constantine. Oxford University Press, 352 pages, paperback, $15.95.

By Matt Hanson

Published in 1874, The Conquest of Plassans is the fourth installment in Émile Zola’s epic Rougon-Macquart novel sequence. The twenty-volume chronicle traces the fortunes of the Rougon-Macquart family through the social tumult of 19th century France. Thanks are due to the Oxford University Press for this new English translation of the novel, which the publisher states is “the first modern translation in 50 years.” In Conquest, Zola trains his empirical and critical eye on a particularly toxic mix of religion and politics when they insinuate themselves into the malleable social landscape of a small provincial town.

Plassans is a fictional stand-in for Aix de Provence, the northern country where Zola spent much of his early life and met his lifelong friend Paul Cezanne. The town is comfortable in its sleepy rhythms and rural splendor, but that same native innocence makes it ripe for the plucking for any adept opportunist with a plan for assuming power. Zola mainly focuses how religious hypocrisy and political chicanery come to dominate this bucolic scene, manipulating the people of Plassans, a town where gossip and concern for social status catch like brush fires.

Inspired by Balzac’s encyclopedic Comedie Humaine, but with a ‘scientific’ thrust to its vision of overarching social and moral decay, Zola’s novel cycle dramatizes “the natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire.” The novels can be read either as part of Zola’s over-arching narrative or on their own compelling terms. Each volume indelibly depicts a different aspect of French society high and low, from the power-hungry bourgeois (La Fortune Des Rougon) to striking coal miners (Germinal). Taking a naturalistic approach, Zola’s fiction gives us figures who are products of their environment and examines how heredity, class, and social forces control his characters’ destinies far more than they realize. His sensational subject matter, with its frank (for the time) depictions of sexuality, political corruption, and abject poverty meant that when the books were translated into English at the turn-of-the-century portions were excised or ‘cleaned up.’ Over the past decade Oxford University Press has been bringing out new and unbowdlerized translations of Zola’s novels. The result has not been revelatory, but it has pointed out that Zola was far more than a documentarian. He was a terrific storyteller who knew that he was drawing on poetic myth and archetypes as well as facts to make his case.

The Conquest of Plassans begins with the arrival of the brooding, laconic Abbe Faujas (emphasis on the faux) and his stern mother. They rent an attic room in the pleasant home of Francois Mouret and his wife Marthe, who is also his cousin from the affluent but disturbed Rougon side of the family tree. Mouret is hardly a religious sympathizer. Styling himself as a cranky, small-town Voltaire, he enjoys humorously commenting on the treachery of the clergy. What no one realizes until far too late is that Mouret’s sarcasm is more accurate than even he imagines.

Faujas is a mysterious and rather exotic presence to the curious Mourets, with his deep silences, his dark, shabby robe and his Spartan living conditions. (Zola puts his distinctive spin on Tartuffe, Moliere’s classic study of religious hypocrisy.) Faujas is ostensibly there to help out the local diocese, but his true intentions toward the town are prefigured early on: “Faujas stretched out his arms in an ironic challenge, as though he wanted to pull Plassans to his broad chest and suffocate it. He muttered: ‘So much for those fools smiling this evening as they say me crossing their streets!’” The abbe often mocks the people of Plassans — not just because he’s corrupt, but because he senses just how easy his conquest will be. After all, he comes in the perfect disguise. What decent, respectable person would dare question the motives of a man of the cloth?

The abbe’s ultimate goal isn’t just his own lust for power but also that of his greedy paymasters back in Paris. We discover that Faujas has been sent by the Bonapartist party to win over the popular opinion of Plassans. Faujas’s specific bosses are not disclosed, but his power plays are undoubtedly aimed at drumming up greater glory for Louis Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I. The bitterly hated “Le Petit Napoleon” had recently seized dictatorial control of France through intrigue, deceit, and brutal violence in an 1851 coup d’état. Solidifying his support by burnishing his public image out in the provinces is part of the new Emperor’s strategy for strengthening his hold on authority. Faujas is there to make it happen by proxy.

When Zola wrote the novel, the political wounds of the coup were still fresh in the minds of the reading public and his characters. Some members of the Rougon family had even participated in the Bonapartist coup themselves in earlier books in Zola’s cycle. In Plassans, Zola shows them smugly drinking away the government pensions they had earned by betraying their comrades during the political upheaval just a few years prior. Their backstories are available in other volumes, but Zola’s message — that money undermines fraternity and moral generosity — comes across clearly.

Marthe Mouret doesn’t suspect Faujas of double-dealing and neither do her neighbors, who are more than happy to invite the mysterious Abbe into their social circle. Having a pious representative of the church in the drawing room brings social cachet and status to the credulous townspeople. Marthe falls hard for the Abbe’s fake religiosity and becomes neurotically fascinated with him. To make matters worse, she also carries some of the genetic traits of her grandmother, Tante Dide, the Rougon matriarch who had been institutionalized with dementia and who is spoken of in anxious whispers.

Marthe spends hours on her knees, less out of a desire for redemption than from a neurotic fixation on mortification before the religiously demanding, socially ambitious Faujas. As time goes by, her fixation on the cleric and her compulsive desire to confess even her most negligible sins to him turn into an obsession. Her alienated husband is increasingly bedeviled by her creepy behavior.

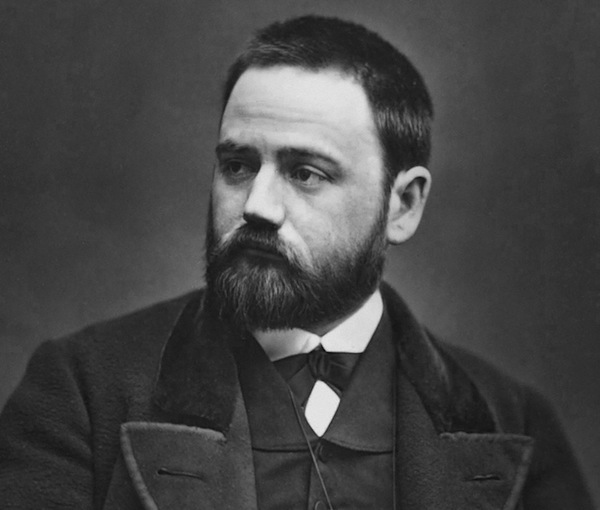

Author Émile Zola — his prose doesn’t flinch in showing how idealism can be manipulated, corrupted or sold outright. Photo: Étienne Carjat

Zola was far ahead of his time in perceiving the symbiotic relationship between pious devotion and sexual hysteria. At times, Marthe foreshadows the repressed housewives lusting after the subversively attractive priest in Jean-Pierre Melville’s film Leon Morin, Pretre. She becomes Faujas’s unwitting pawn through what might be called the ‘erotic’ side of confession, a seamy attraction generated by the intimate and voluptuous disclosures between penitent and authority figure.

Faujas uses Marthe’s unquestioning devotion and social standing as leverage to maneuver his way into the good graces of Plassans society. Through rumormongering and Machiavellian manipulation, he eventually wins over the credulous townspeople. With public support, Faujas gains control of the local church, politically outmaneuvers the feckless local priests, and installs himself as a major force in the town’s affairs. The only character who notices this gradual takeover of the town is the cantankerous Francois, who goes increasingly mad as his own family and the people of Plassans turn against him. Eventually, the frustrated husband takes matters into his own hands, his hatred of Faujas’s diabolic scheming and Marthe’s fears of damnation culminating in an apocalyptic climax.

Christopher Hitchens, a major Zola fan, once remarked that there was nothing you couldn’t get away with if people called you reverend. The Conquest of Plassans is particularly relevant these days, when religious ‘ideology’ cynically passes itself off as public policy, and faith-based initiatives are no more than thin veils for political ambition. Zola’s fast-paced, journalistic prose hones in on how idealism, when faced with an implacable hunger for power, can be manipulated, corrupted or sold outright. Entertaining yet incisive, The Conquest of Plassans remains a devastatingly acute reminder that religion and politics make surprisingly compatible bedfellows.

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: 19th century French literature, Emile Zola, French literature, Oxford University Press, politics, religion

This is really intriguing – makes me want to return to Zola!