Book Review: Daniel Kehlmann’s “F” — An Amusing Look at Our Disjunctive Modern Life

In F, vertigo is often palpable. Evil exists. “The terrifying beauty of things” does, too.

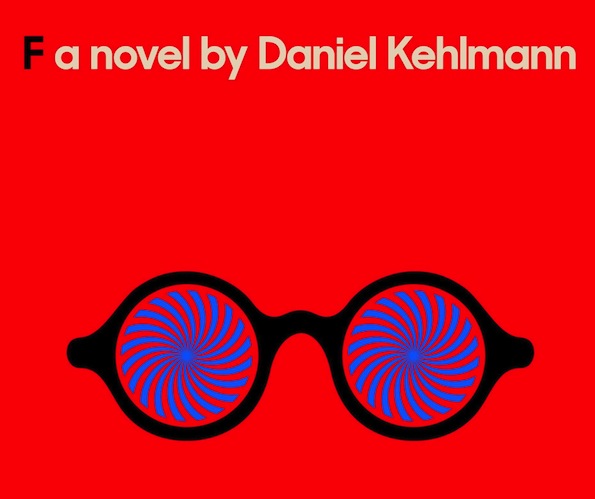

F: A Novel by Daniel Kehlmann. Translated by Carol Janeway Brown. Pantheon, 272 pages, $25.95.

by Kai Maristed

“Good literature comes from an economy of means, great literature from extravagant squandering. It gives one the impression that everything is easy and that imagination knows no limits.”

— Daniel Kehlmann in praise of E.L. Doctorow, July 4, 2011.

Daniel Kehlmann, one of the most brilliant writers working today in any language, has not been thrown off course by early success. His soaring, daring new novel, F, delivers the proof.

Born in Munich in 1975 to an actor mother and theater-director father, Kehlmann grew up in Vienna, studied philosophy and literature, and published his first novel, Beerholm’s Vorstellung, at age 22. Vorstellung (the word can mean both ‘show’ and ‘idea’) tells the story of a magician whose mastery of craft opens a personal trap-door of endless illusion. This debut novel, which foreshadows certain tropes – if not obsessions – of F, was greeted by critics cautiously, as typified by the caveat from one reviewer that it was “too self-conscious…although the author may be on the right path.” Kehlmann responded with five books in seven years, including the multiple prize-winning 2006 novel Measuring the World, a strangely moving chronicle of the intertwined lives of Carl Gauss, mathematician, and Alexander von Humboldt, world explorer.

When people talk about the “novel of ideas,” they generally mean a narrative built around a single idea, or maybe two or three at most. It is not a category of fiction readers especially seek out. The driving abstract concept has a tendency to become the protagonist, draining life from its marionette-like supporting characters. Who wants to have to read Sartre again?

F is a novel of ideas of a different kind. It’s a 256 page cornucopia, pouring out what-ifs and alternative perspectives on the human condition as if its author could hardly stop the flow even if he wanted to. Which is not to say that F lacks a unifying narrative. In fact, this shortish novel is a page-turner, spiked with funny, deadpan observations of our disjunctive, modern, so-called life.

The figure at the center dominates mainly through his absence. Arthur Friedland, twice-married father of three boys, is a wannabe poet notable for both his consistent failures and his stubborn, proud indifference to failure. Everything changes the day a chance on-stage encounter with a sleazy hypnotist galvanizes him to abandon his boys on the nearest doorstep and disappear. The kids won’t see him again until they are grown up, but from his remote self-exile Arthur soon begins to publish novels of deep, bleak social impact, inciting a rash of suicides – and winning enormous commercial success. (F is a work of fiction, remember).

It is the three sons, Martin and his half-brother twins Eric and Ivan, whose voices carry the tale forward. Martin the helplessly gluttonous Catholic priest, Ivan the sophisticated art dealer, Eric the hedge-fund millionaire: each of these quasi-orphans, while enjoying outward prosperity, is tortured by a sense of personal fakery that is more or less deserved. Only Eric’s daughter Marie, whom we begin to know in the final pages, has a sense of honesty about herself – even though she’s a guilt-free whiz at lying to those around her.

Kehlmann likes to set introverted, flawed, irrationally likeable characters loose in a maze of difficulties. Sexless Martin has fled life’s challenges to serve a God he can’t believe in; his one true passion is to win the championship in speed-solving Rubik’s Cube. When a punk confesses to having badly wounded a man and left him alone in the street, will Martin grant absolution, or call the police? Businessman Eric has so many secrets to juggle – his mistress, his paranoid visions since childhood, and now the looming revelation that he has embezzled and lost all his clients’ money – that not even the morning cocktail of tranquilizers and antidepressants can hold him together. Meeting his wife in the hallway, he inquires, “‘Did you sleep well?'” While thinking, “I ask her this every morning although I have no idea what it’s supposed to mean. Either you’re asleep or you’re awake. But I know from television that people ask one another these questions.”

Only Ivan, the art student who shelved a career of his own in favor of ‘forging’ lucrative paintings signed by a complicit artist well past his prime, appears to have evaded, after one early attack, the obsessive familial grinding self-doubt and angst. Through Ivan, whose Oxford thesis is delightfully titled ‘Mediocrity as an Aesthetic Phenomenon,’ Kehlmann has a rollicking good time satirizing the holy pieties of the art world. It’s territory he has visited before: his 2003 novel Kaminski and Me featured a desperate journalist stalking a reclusive old artist. The young Ivan/aging Eulenboeck pair here feels much like an inverted, happier version of that bond. Another Kehlmann preoccupation revisited in F is Fame itself, that being the title of his 2009 volume of interlocked short stories in which fact and desire merge, separate, and merge again.

Intellectual brilliance doesn’t necessarily imply or guarantee perfection, whatever that might be in a novel. As a character, the quickly sketched Arthur remains a functionary. Even less convincing, because he is more worked-over, is Martin: his long-winded arguments for God’s non-existence are tediously familiar in a decade dominated by the likes of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. With the exception of young Marie, the women – mothers, lover, wife – are weak, either pathetic or antipathetic. (Next time out, one would like to see Kehlmann stretch his imagination to inhabit the mind of a complex woman.) And some readers may be frustrated by the lack of anchoring to place (we’re in a mid- to large German-speaking city) or current events (time: somewhere in the present.) Others may welcome this Nabokovian ambiance.

A particular pleasure of reading Kehlmann is his ease among the so-called hard disciplines. Mathematical and scientific paradoxes can illuminate or bedazzle; they are as integral to his fiction as pigment is to paint. The 1999 novel Mahler’s Time took us into the incandescent mind of an inspired physicist. In F, children argue, as children will do, about infinity. “‘Does space up there just keep going?’ ‘Maybe there’s a wall.’ ‘But you can always keep flying. You could make a hole in the wall.’ ‘But if it’s the most massive wall in the whole world?’ ‘Then imagine you have the pointiest tool.’ Arthur Friedland sends us a gloomier message: ‘Don’t forget: nobody inhabits the brain […] the eyes are not windows. There are nerve impulses, but no one reads them, counts them, translates them, and ruminates about them […] There’s nobody home. The world is contained within you, and you’re not there.’ In F, vertigo is often palpable. Evil exists. “The terrifying beauty of things” does, too.

As narrative time accelerates, and pages remaining to the last line dwindle, the intricately crafted F opens up, paradoxically, with a cascade of thrilling ‘clicks’ of merging elements. Something like a fast-spinning solution to Martin’s beloved Rubik’s Cube.

You might even want to go back and read F again.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other publications. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, a novel.

Tagged: Daniel Kehlmann, F: A Novel, German fiction, Kai Maristed