Arts Commentary — Big Money for Artist Activists From the Robert Rauschenberg Estate

It’s important for there to be funds, curators, institutions, and audiences for art that can speak truth to power in unconstrained ways.

By Debra Cash

Taking it to the streets? The estate of artist Robert Rauschenberg just announced that it is rolling out a series of open calls for proposals to support two year fellowships for artists, designers, and other creative thinkers working to “move the needle” on social and political issues. The rich awards range from a high of $100,000 (expect these to go to people we have heard of before) to $2500 (presumably going to emerging artists and those working close-to-home).

This announcement, no doubt a significant time in the making, coincides with a trend in arts philanthropy towards supporting politically engaged and socially relevant work. It also comes at a time when artists are demanding to take a place at the table, and be heard through or from behind their work when serious public issues are discussed.

In August, a Facebook group called Artists Against Police Brutality/Cultures of Violence was established in the wake of the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri (full disclosure: I “liked” and joined). More problematically, an organization that calls itself the US Department of Arts & Culture sent out a post-Ferguson call for people to sign a “citizen artist’s pledge” to demand an end to militarized police forces. They called for artists and creative activist to join “to bring justice to victims of publicly funded racism” (which is great, but why leave out the private stuff?).

I’m all for politically informed art-making, and have been very moved by, for instance, Fernando Botero’s Abu Ghraib series, Stephen Hayes’s Cash Crop installation about the slave trade, William Kentridge’s searing animations at the edge of South African apartheid and the outpouring of work across genres that arose out of the fight against AIDS and has exposed the exploitation of women and children.

However, the folks behind the citizen artist’s pledge were being profoundly disingenuous shading into duplicitous: the fine print on the call indicated that USDAC is (unsurprisingly) not a federal entity. Who were they speaking to? And who did they think would listen?

It’s important for there to be funds, curators, institutions, and audiences for art that can speak truth to power in unconstrained ways, a constellation of groups that create solidarity and encouragement to the people working for social change. I’m pretty impressed that most contemporary visual art institutions — and some more omnibus collections — not only look for that work, but put their stamp of approval behind it.

However, when art is defined as fundamentally instrumental — that is, made expressly to create certain conditions in the external world — and when only art that takes on social change is deemed valuable, we are in a slide towards didacticism, not to mention a world that has no space for Mozart or Rothkos.

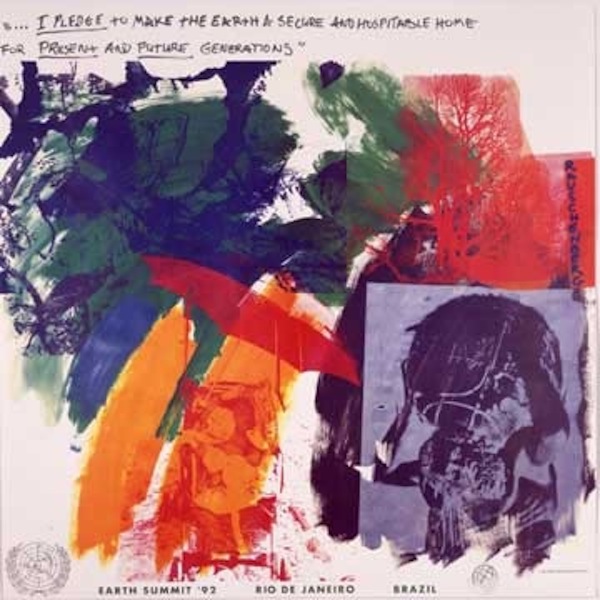

The artist who said “The artist’s job is to be a witness to his time in history” and created the first Earth Day poster in 1970 knew better.

Robert Rauschenberg’s example should set both a baseline and offer a guiding light.

Debra Cash has reported, taught and lectured on dance, performing arts, design and cultural policy for print, broadcast and internet media. She regularly presents pre-concert talks, writes program notes and moderates events sponsored by World Music/CRASHarts and cultural venues throughout New England. A former Boston Globe and WBUR dance critic, she is a two-time winner of the Creative Arts Award for poetry from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and will return to the 2014 Bates Dance Festival as Scholar in Residence.

© 2014 Debra Cash

Maybe it would be a good idea to read before you write. I hope anyone who is inclined to believe this writer’s accusations takes the time she didn’t to actually read what this project is about. The “U.S. Department of Arts and Culture” (USDAC) is a seriously playful art and social change project that has set out to build a citizen movement to perform the public interest in culture, mobilizing artists to help build a future we want to inhabit.

We understand that artists’ skills and approaches can be powerful drivers of social healing, whether the subject is climate crisis, inequality, or other pressing issues. We’re working on the local level (e.g., we’ve already had a dozen local art-infused dialogues in communities across the country, spearheaded by “Cultural Agents” selected from a pool of 100 who answered our first recruitment call) and nationally. The latter is my bailiwick (I have the honor of serving as “Chief Policy Wonk”), with one overall goal being to build a National Cabinet of thought and action leaders to create and share a roadmap for cultural democracy.

Along the way, we’re acting on specific issues. The USDAC Call: Creativity for Equity and Justice focuses on “publicly funded racism” because it’s about police militarization and its victims. Readers may recognize the names of many of the remarkable artist-activists who endorsed the launch of this national action, which is gaining more and more traction every day. We did not put out the Call asking anyone to sign anything, nor it is a pledge; those are both this writer’s errors. We asked artists to “use our gifts for peace and justice, sharing images, performances, experiences, writings, and other works of art that raise awareness, build connection, cultivate empathy, and inspire action.”

I won’t hold my breath waiting for an apology, but one is warranted.

The USDAC asks people to “join” their list and volunteer their services and networks. The text of the Citizen Artist’s Pledge affirms many lovely ideas, including that access to culture is a fundamental human right. This is a narrower use of the term culture than any anthropologist or ethnographer would use, because none of us live in a vacuum. However, if I didn’t believe that was true about art and art making, I wouldn’t have devoted my professional life to this work. Arlene Goldbard and I are on the same page here.

My very real concern is with a) the disingenuous name, since among other things it presumes that while you don’t have to be a legal citizen (which is fine with me) to be involved, you do have to be a progressive and b) the pledge — yes, it’s a pledge, and you sign by clicking — which includes the sentence “As a founding Citizen Artist, I pledge to all others affirming these values my creativity, integrity, and commitment to cultivate the public interest in art and culture and catalyze art and culture in the public interest.”

This is a longer argument for another time, but just because an artwork is not created in order to make social change does not mean it is not a public good. That’s why the striking mill girls demanded Bread and Roses.

No, I don’t need to apologize.

You’re confusing two things. The Call you referenced in your piece is not a pledge. There is indeed a Citizen Artist’s Pledge as part of the project, but it was not a prerequisite of the Call or directly related in any way.

No point in trying to explain irony if your idea about using a formal name for a creatively subversive purpose is that it’s “disingenuous.” Google the Yes Men. If you think it’s disingenuous that they pretend to be corporate execs, well, we just have to declare an unbridgeable gap.

As for the other straw men and red herrings….