Book Review: An Evocative Biography of Zionist Agitator and Writer Vladmir Jabotinsky

There’s room to wonder if Vladmir Jabotinsky would have accepted Menachem Begin, Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu as his legitimate Zionist heirs. Might he have been repulsed by their mash up of realpolitik and Judaism?

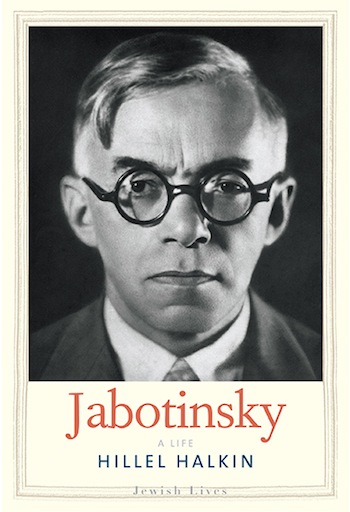

Jabotinsky: A Life, by Hillel Halkin. Jewish Lives, Yale University Press, 256 pages, $25.

By Harvey Blume

Given the war, or rather, wars, roiling the Middle East, this is a particularly good time to rethink the legacy of Zionist leader Vladmir Jabotinsky, as Hillel Halkin invites readers to do in his compact and evocative new biography.

Born in Odessa in 1880, Jabotinsky was, among other things, a gifted writer in a variety of genres, from journalism to plays, poetry, translations — Halkin calls Jabotinsky’s rendition of E.A. Poe’s The Raven a “high-water mark of Hebrew translation” — and novels. It was, in fact, the impression that Jabotinsky’s novel The Five (1935) made on Halkin, who regards it as one of the great works of twentieth century Russian literature, that drew him to this complex and controversial figure in the first place. But Jabotinsky is remembered in history not for his literary fiction, however accomplished, but for his politics. In 1925, he founded and led a faction of Zionism that he called Revisionism, which challenged core assumptions of the movement Herzl set in motion with the first Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897.

Zionists had agitated for a homeland, a refuge, a cultural center for Jews contending with relentless anti-Semitism in Europe, a place that could foster national rebirth. Jabotinsky, at one point, derided this as nothing more than a longing for an “amusement park for Hebrew culture.” He demanded not merely a homeland but a Jewish state. Many of his peers had the same desire but preferred not to voice it aloud, since to do so might alarm and alienate the British who governed Palestine after World War I, and were always trying to reconcile the promises they made to Arabs with the utterly irreconcilable promises they made to Jews.

The official line of Zionism was that conflict with the Arabs in Palestine could be avoided. Jews settling in what was called the Yishuv would bring economic and political benefits which both, the Jews, then a small minority, and the Arabs, the majority, would appreciate. Jabotinsky thought this high-minded view not only absurdly utopian but also insulting to the Arab population. In his 1923 essay “An Iron Wall,” he argued that: “Arabs have the same instinctive love and inbred zeal for Palestine that the Aztecs had for Mexico and the Sioux had the prairies.” He scorned as a “childish fantasy” the notion that Palestinians would peaceably accept what he, for one, hoped would amount, in the end, to a Jewish majority in Palestine; to his mind it showed nothing but concealed contempt for Arabs to suppose they would “sell out their homeland for a railroad network.”

Jabotinsky could not be accused of dreaming that Palestine was a land without people ripe for a people without a land. He fully acknowledged the rootedness of the Arab population, which, he was sure, would take up arms to maintain its dominance. His message to Zionists was that it was better to face that fact than to obscure it. The “iron wall” he called for would establish that under no circumstances could Jews be expelled from Palestine; only after that point was made for good could genuine peace be negotiated between Jews and Arabs. What we now call ethnic cleansing was not part of the Revisionist program. That’s clear from the first paragraph of “The Iron Wall,” where Jabotinsky asserts that “the expulsion of the Arabs from Palestine is absolutely impossible,” and that there would “always be two nations in Palestine.” On the other hand, from early on in his Zionist enterprise he espoused what we now call a Greater Israel, one stretching from the Mediterranean to the West Bank of the Jordan River.

Jabotinsky died in 1940, at age sixty, during a speaking tour in the United States, loudly mourned even by those on the left who had vociferously opposed him. We cannot know what he would have made of the 1947 United Nations resolution that partitioned Palestine and brought Israel into being. Nor can we know what he would have made of the post-1967 blossoming of Israeli settlements on the West Bank. Would he have approved them as fulfilling his dream of a Greater Israel? Or would he have found the religious/messianic motivation for many of them utterly alien?

Jabotinsky was a Jewish nationalist, to be sure, but never one to wrap his aims in Torah. He spoke of the West Bank and not, as Biblically inspired settlers do, of Judea and Samaria. Today’s Likud party traces itself to Jabotinsky’s call for a Greater Israel and his emphasis on nationalism as opposed to the ideas about socialism prevalent in Zionism during its formative years. Still, there’s room to wonder if he would have accepted Menachem Begin, Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu as legitimate heirs. Might he have been repulsed by their mash up of realpolitik and Judaism?

***

There is much to like about Jabotinsky, including questions he raises that can’t decisively be put to rest. Halkin is thoroughly charmed by him, as were many, including opponents, who came in contact with this roguish, romantic, culturally sophisticated Zionist, so different in his tastes and comportment from his peers. Halkin is, in addition, charmed by Odessa, which he visited in the course of his research. Turn of twentieth century Odessa was, he records, “a unique place” for Jews, “the only large Russian city they weren’t barred from.” In Odessa: “Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Moldavians, Greeks, Turks, Tatars, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Armenians mingled.” Moreover, of these ethnicities, Jews “were the largest. ”

Vladmir Jabotinsky — in his fiction he expressed a vision that could be tied to a fascist aesthetics.

Jabotinsky’s mother, Chava, wanted her son to speak Russian, as she tried to do, though Jabotinsky recalled that her efforts only “wreaked havoc” on the language. Her native tongue was Yiddish, which she discouraged Vladimir — in Hebrew, Ze’ev— from using, but to no avail; he achieved fluency in it, along with, as per Halkin, Russian, Italian, German, Hebrew, French, English and Polish.

Looking back on Odessa, Jabotinsky fondly described it as “a thievish city,” unable to be “profound about anything.” It’s easy to see why Isaac Babel set his famed tales of Jewish gangster king Benya Krik in this beguilingly dishonest place. Odessa did not lack for traditional expressions of Jewish culture but did not impose them, being less subject to “rabbinical influence than other Eastern European Jewish communities.”

Jabotinsky grew up in a kosher home but debated Nietzsche with friends, never the niceties of Talmud. A railroad trip through the shtetles of the Ukraine and Galicia did nothing to settle his personal Jewish questions. What he saw of the mix of orthodoxy and poverty in the shtetles caused to him ask, “Can this people be mine?” And then there was Rome, where he went in 1898 ostensibly to study law but in fact to carouse, expose himself to the arts, and absorb the excitement Italians felt about the unification of their country. His experience of Italian nationalism helped mold him; it might be said that he wanted the Jerusalem he later fought for to be more like the Rome he had so thoroughly enjoyed than it could ever be.

Jabotinsky returned to Odessa in 1901 to write a popular newspaper column, just as anti-Semitism was reaching new heights in Russia and the Ukraine. In 1903, Jews once again confronted the blood libel, the charge that they killed Christian children in order to use their blood in Jewish ritual. In April of that year, the Kishinev pogrom broke out, the most murderous since the seventeenth century, and Jabotinsky threw himself into efforts to organize Jewish self-defense. Kishinev was, in a sense, to him what the Dreyfus Affair had been to Theodore Herzl. He continued to write seriously and to publish but politics trumped all other callings.

Halkin portrays all this well, as he does the peculiar fact that Jabotinsky, a romantic in many ways, was simultaneously clear-sighted and realistic about history as it unfolded. During World War I, he wanted Jews to support England and helped organize a Jewish Legion to fight on the English side. David Ben-Gurion, on the other hand, was meanwhile urging Jews to align themselves with the dissolving Ottoman Empire. When World War II was on the horizon, Jabotinsky’s sense of the catastrophe in the offing for the Jews of Europe almost suggests its real dimensions.

Hillel Halkin, a novelist and linguist who moved from the United States to Israel in 1970, brings considerable literary skill and grasp of history to this biography, but is perhaps a bit too charmed by his subject. Halkin is keenly aware of how twentieth century politics helped frame disputes within Zionism. Jabotinsky did not hesitate to portray David Ben-Gurion, his ideological opposite in the movement, as a Bolshevik, and it is the case that Ben-Gurion did, like many socialists, however briefly, sympathize with the Bolshevik Revolution. Ben-Gurion, in turn, would characterize Jabotinsky as nothing but a would-be Jewish Il Duce. In fact, Jabotinsky was as profoundly critical of Mussolini as Ben-Gurion was of Lenin.

But in his fiction, more openly than in his politics, Jabotinsky did express a vision that could be tied to a fascist aesthetics. Here is a passage from his novel, Samson the Nazarite (1926), in which Samson witnesses a Philistine religious pageant:

Suddenly, with a rapid, almost inconspicuous movement, the priest raised his baton, and all the white figures in the square sank down to their left knee and threw their right arm toward heaven — a single movement, a single, abrupt, murmurous harmony. The tens of thousands of onlookers gave utterance to a moaning sigh.

Samson is “stunned by spectacle of thousands of limbs moving in unison to a single will,” and feels he has just been exposed to the underlying “secret of all state-building people.” It’s bothersome to him that his own people, the crude and fractious Israelites, don’t seem capable of such fanatic unity. In the 1930s, Walter Benjamin observed that fascism tended to aestheticize politics, burnishing and embellishing it as if it were art. Jabotinsky never took this impulse as far as some — certainly never as far as Leni Riefenstahl aimed to in her Nazi extravaganza, Triumph of the Will — but it is clear Jabotinsky entertained a version of that impulse.

More to the point, in reconsidering Jabotinsky and his legacy, is that history has proven the core tenet of Revisionist Zionism wrong. Israel has established and defended its iron wall many times since Jabotinsky wrote his essay. But the cycle of Jewish-Arab violence, dating from early on in Zionist approaches to Palestine, continues unabated. One must look elsewhere than to Revisionism for a way to end it.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: Harvey Blume, Hillel Halkin, Israel, Jabotinsky: A Life, Jewish Lives, Jewish nationalism, Judaism, Revisionism, Short Fuse, Vladmir Jabotinsky, Yale-University-Press

It’s amazing how easy it is for American Jews to stroke their shaved cheek and reconsider gravely the questions of origin. It goes back to Moses, after all. And Jabotinsky. Netanyahu is reflexively waging 20th century Cold War horror, just like Putin, another fossil. Bad. How many bad wars did the U.S. pursue since the Cold War? Enough. Yet: did American Jews rethink the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights and the Constitution every time one of our bad leaders wasted lives and hurt the nation terribly and stupidly? No, we just voted them out. Israel is no different: you don’t have to rethink its existence and its raison d’etre every time a bad leader is murderously wrong. The hangover from the 20th century isn’t over, but it doesn’t mean we need to get drunk on the 18th or 19th century to agonize over our beginnings. Just vote the bums out.

Glad you think the time is ripe for another look at Jabotinsky. Plunkett Lake Press has just acquired the ebooks rights to the 1800-page biography by Shmuel Katz and will be making it available soon.

This is a most excellent review and, as you said, this is a good time for considering the life of this man.

I will add that I have had a long secret desire to visit Odessa — the Odessa of my imagination.

For a book that describes Jabotinsky’s life and his Revisionist varient of Zionism from a more anti-imperialist left perspective, readers might also want to check out the book by Lenni Brenner, The Iron Wall: Zionist Revisionism From Jabotinsky To Shamir, that Zed Press published in 1984.According to the book’s cover: “The Iron Wall is a comprehensive and documented history of Revisionism which is now the dominant ideological tendency in present-day Zionism. Starting with the pre-Revisionist period of Vladimir Jabotinsky’s life, this book traces the origins and the course of what used to be regarded as the lunatic fringe of Zionism, but which has, since 1977, dominated the Likud Administrations…Jabotinsky, the movement’s founder, laid down ideological guidelines not merely for his own tendency within Zionism, but, indeed, increasingly for Zionism as a whole. He was explicit in his racism, his colonialism, and the pro-capitalist nature of his movement. Arguing that no compromise with the Palestinians was possible, his stance led the Revisionists into close connections with Mussolini as well as terrorism against the Arabs.”

Helen, thanks for the tip about the 1800-page Shmuel Katz bio. You get first dibs. Look forward to your take!

Fred, I share your interest in Odessa, even its Brooklyn offshoots.

bobf, Sanctimony and real or pseudo religiosity have helped fuel Likud. Jabotinsky, who died in 1940, was a secular man. I can’t hold him responsible for religion’s seeming stranglehold on Israeli politics. As for Jabotinsky being “explicit in his racism,” it’s worth noting that he fully condemned what he saw of Jim Crow in the United States, writing that, “tens of millions of citizens live shockingly without rights just because of the color of their skin.”

I think he was more complex than you are allowing.

andrei, old friend, on these issues i am relentlessly contrarian, not least of all toward myself. other people’s shrill certainties drive me back to history. . .

but vis a vis, “Just vote the bums out”, i’m with you, with regard both to putin & netnayhau. down with both!