Culture Vulture: A Theatrical Wonder in the Berkshires

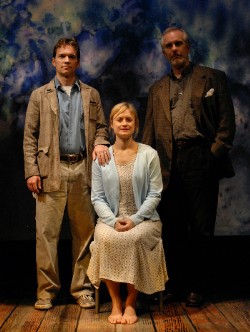

Chad Hoeppner, Rebecca Brooksher, and Kevin Hogan In the CTC production of Molly Sweeney Photo: Rick Teller

Reviewed By Helen Epstein

Molly Sweeney by Brian Friel. Directed by Michael Dowling. Staged by the Chester Theatre Company, Chester, MA, through July 11.

This summer Chester Theatre Company (CTC) Artistic Director Byam Stevens is exhorting theatergoers to “free the inner audience” within them. Theatergoers, he says, have become like critics, losing a sense of honest engagement with drama. The critic, he argues, is a character invented by modern journalism, a charlatan uneducated in theater history and practice, rating cultural productions like a Consumer Reports evaluator, making judgments from a (superior) distance rather than partaking of the theatrical experience.

Audiences, he argued, in an introduction to the company’s first production of the season, Brian Friel’s Molly Sweeney, should become theater colleagues rather than “voyeurs”; they should join actors, designers, and directors in engaging directly with the playwright’s work, “eschewing the soul deadening thumbs up/thumbs down shortcut,” experiencing, actively trying to understand, rather than just looking.

Just looking is the subject of Molly Sweeney, which is the opening production of the season at Stevens’s wonderful theater in the Town Hall of Chester, Massachusetts, a tiny valley town in western Massachusetts so isolated that it’s a wonder he can fill the auditorium’s 128 seats. Chester is located on Route 20, a few miles east of the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, a half hour’s drive from the Berkshire hub of Lenox-Stockbridge and an hour from Northampton. Nevertheless, theater cognoscenti regularly make the drive, and some precede the show with dinner at the Pioneer Grill and Pizzeria, an unassuming, little restaurant where the fruits and vegetables come right out of the garden.

A similar freshness imbues the productions of the CTC, this week Molly Sweeney by accomplished Irish playwright Brian Friel. This is a play about engagement at its most basic level: through what senses do each of us perceive the world we live in? What happens when we try to improve on that arrangement?

Rebecca Brooksher in CTC's Molly Sweeney Photo: Rick Teller

Friel based the play on an early New Yorker article by neurologist Oliver Sacks. In October of 1991, Sacks received a telephone call about a 50-year-old man he called Virgil, who had been virtually blind since childhood. Virgil had been offered a miracle cure, a chance to see the world. “There was nothing to lose,” Sacks wrote, “and there might be much to gain.” But, in fact, it was a miracle that misfired and wound up with Virgil losing his job, his house, his health, and independence, “leaving him a gravely sick man, unable to fend for himself.”

Friel transforms 50-year-old American Virgil into 34-year-old Irish Molly Sweeney, creates a ne’er-do-well husband named Frank, and an opthomologist identified as Mr. Rice. The play is performed as a set of intertwined monologues that the three actors deliver directly to the audience from three chairs: a stool for the callow, impulsive, but loving husband; a comfortable easy chair for the physician whose professional and personal life has been arrested by his wife’s desertion to one of his medical colleagues; a plain hospital chair for the spunky and sensual Molly, first blind, then sighted, then blind again.

The directness of their speeches to the audience are reminiscent of a psychotherapeutic encounter; their isolation from and misunderstanding of one another is pronounced. The emotional intensity is sometimes broken by the distraction of Lara Dubin’s lighting design, which is meant to evoke Molly Sweeney’s changing visual field but, like some of the ultra-high-tech lighting I’ve seen lately, ends up being distracting.

Michael Dowling cast and directed the play well. All three actors—Rebecca Brooksher as Molly, Kevin Hogan as Mr. Rice, and Chad Hoeppner as Frank Sweeney—are accomplished and almost always interesting to watch and hear. They convincingly bring to life Friel’s meditation on this extraordinary true story, which combines fairy tale and Faustian bargain. “Beware of strangers bearing gifts” and “Be careful what you wish for” are only two phrases of folk wisdom that resonate through this deeply intriguing play. Like many such adaptations from real life, however, Friel had to choose and simplify in order to create a satisfying drama.

Afterwards, I looked up Sacks’s Anthropologist on Mars (where the New Yorker piece has been collected), to reread and reflect on the many complex issues the production brings to theatrical life.

==================================================

Helen Epstein is the author of the biography Joe Papp and a profile of art historian Meyer Schapiro available on Kindle/Amazon. She will be speaking about memoir on July 8 at Cary Library in Lexington, MA.

Tagged: Berkshires, Brian Friel, Byam Stevens, Chester Theatre Company, Culture Vulture