Jazz Commemoration and Comment: Horace Silver, 1928 – 2014

He knew what he wanted to do, he did it, and he took millions along for the ride.

The late Horace Silver — Like no one else in jazz and like very few others in music – a superb representative of his own genius, a canny self-marketer, a fully self-realized man.

By Steve Elman

Everything Horace Silver touched turned to melody. But then the melody faded away.

The news of Silver’s death (on Wednesday morning June 18) came as no surprise to people like me, who’d been following his career since discovering him in the 1960s, but it left me grieving nonetheless. I suspect many others feel the same way. His last recording session was in 1998 (“Jazz Has a Sense of Humor,” Verve), when he was 73. As the 2000s went by, the silence was deafening, and the dread was palpable. In 2007, bassist Christian McBride reported on his blog that Silver was suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease.

Again – as with Max Roach, George Russell, and many other jazz musicians whose conditions were kept secret because their families valued their privacy and wanted to preserve the musicians’ dignity – dementia stole years of their music and left those who loved them with a heartbreaking dilemma: how can you mourn for someone who hasn’t yet died?

In some ways, artists who linger on the fringes of rationality in early old age suffer a terrible fate: they begin to be forgotten even as they should be reaching senior-league canonization. Witness the outpouring of gratitude to Dave Brubeck in every concert he gave after he turned eighty, and the love audiences show for Roy Haynes as he continues to perform, pushing ninety. Those whose brains betray their art can be honored by their colleagues with tribute concerts and national awards, but the praise has a bizarre edge. We wish to remember artists in their prime, or at least to be comforted by the assurance that an artistic flame continues to burn, perhaps less brightly, but with a purer glow. When greatness is only in the past, and the artist becomes an empty vessel, fans hear the bells tolling for themselves. They see the pathos that their own lives might someday inspire, and they recoil from the thought.

Horace Silver deserved to live to a golden age. Genial, masterful, gracious, incredibly tuneful, he was like no one else in jazz and like very few others in music – a superb representative of his own genius, a canny self-marketer, a fully self-realized man. He knew what he wanted to do, he did it, and he took millions along for the ride.

There are superb obits out there – by Peter Keepnews in The New York Times, and by Jocelyn Y. Stewart in The Los Angeles Times, so there’s no need for me to repeat the biographical details. Perhaps I can add some perspective and make some recommendations to those who may not know enough of Silver’s music.

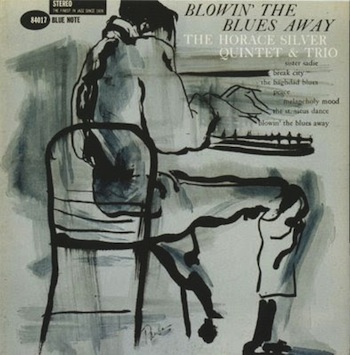

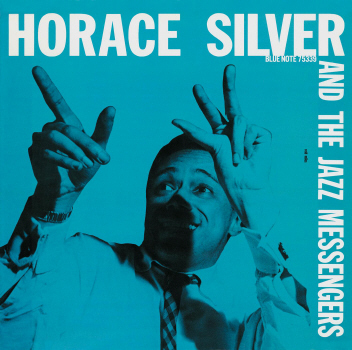

The conventional wisdom about Silver is true, in so far as it goes – that he was one of the principal movers in hard bop, that stream of jazz from the mid-fifties to the mid-sixties that married the harmonic and improvisational innovations of bebop to funk and gospel. He has one of the deepest catalogs of tunes in jazz – and if his compositions were not as sophisticated as those of Ellington, Monk, or Mingus, no one ever surpassed Silver in his ability to write for small ensembles and to conceive of melodies and tune structures that seemed to launch soloists to their best efforts. Those tunes include “Song for My Father,” “The Cape Verdean Blues,” “Nica’s Dream,” “Sister Sadie,” and “Silver’s Serenade.” But there are at least a dozen less- familiar themes that ought to be standards – including “Peace,” “Ecaroh,” “Silverware,” “Dimples,” “Summer in Central Park,” and “Lonely Woman” (unrelated to Ornette Coleman’s classic of the same name).

As a pianist, he was a distinctive and inimitable stylist, basing his sound on that of Bud Powell, but taking Bud’s hard edges and fiery intelligence to a more approachable place for the average listener. He constructed his solos with simple but elegant architecture, throwing in puckish quotes from all sorts of other tunes, punctuating right-hand flow with left-hand clusters that made his piano sound as if it were growling or grumbling, and swinging . . . swinging as no one else has, before or since.

But there was more to Horace Silver’s art than funk and good feeling. His piano trio performances are endlessly fascinating, and they strip away some of the seductive colors of his quintet, so that you can hear the purity and smarts of the music. In a way, he realizes much of what was left undone by Bud Powell, and he mellows Bud’s brilliance with wit.

There were excesses. Silver was known for his “character pieces,” in which he supposedly portrayed archetypes or individuals (“Filthy McNasty” is probably the best of them) and after a while, this idea wore out its welcome. He liked exotic colors for a change of pace in his sets, but the titles of these variety pieces made them sound more hackneyed than they actually were – “Cherry Blossom,” “Mexican Hip Dance,” “The Dragon Lady,” etc.

And then there were the vocal pieces. Silver was never an inspired writer of words, and some of his lyrics are almost painfully naïve or prosaic. He hoped to inspire the world with New-Age philosophy, but the sentiments just got in the way. Several vocal-heavy CDs are best avoided unless you must have everything he ever recorded.

As a body of work, Silver’s compositions are neglected. And, if you discount the occasional lapses, they are amazingly consistent. His last sessions included new tunes that deserve to be covered just as much as his older tunes have been – “Put Me in the Basement” (a contrafact of “Body and Soul”), from It’s Got to Be Funky (1993), “I Want You,” from The Hardbop Grandpop (1996), and “Walk On,” from A Prescription for the Blues (1997), just to name three.

It may be that Silver’s death will bring new interest in his music. For decades now, the incentives of composer royalties have tended to drive musicians into filling their new releases with second-rate originals rather than mining the vast riches of compositions by past masters, but one can hope that Silver will at least have a few more years of notice. A case in point: the SF Jazz Collective made Silver the focus of their 2010 concert tour, and the three-CD set that resulted (available only from sfjazz.org) contains some of the most interesting arrangements of Silver’s music that I’ve ever heard.

There will be commemorative CD sets. There must be commemorative sets. Blue Note issued the vast majority of Silver’s work, and his later CDs came out with Impulse and Verve imprints. All three labels are now owned by Universal, so a limited-edition “Complete Horace Silver,” including unreleased material from the vaults, is a tantalizing possibility. But, at the very least, all of his trio performances from the three labels ought to be collected into one CD set, along the lines of The Trio Sides, a 1976 Blue Note twofer LP, and Ran Blake’s beautiful notes for that set ought to be reissued at the same time.

Two releases on Columbia – Silver’s Blue and It’s Got to Be Funky – bracket the Blue Note years. They’d make a nice set, and Mosaic could take up the slack if Columbia wasn’t willing to do so

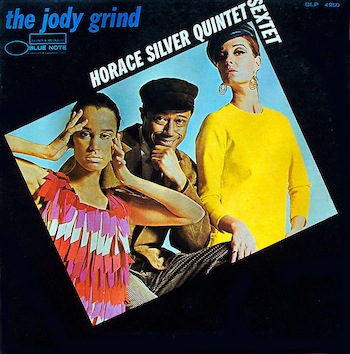

But those matters are for the collectors. As for anyone who doesn’t yet know why Horace Silver was great, I’ll keep my recommendations to two: Silver’s Serenade from 1963 and The Jody Grind from 1966 (both on Blue Note). In both of these sessions, you’ll hear the remarkable empathy of Silver’s working groups and the richness of his compositional gifts. If you want more, the SF Jazz Collective set referred to above (Live 2010: 7th Annual Concert Tour) would reward repeated listening.

To all the words that have been written in commemoration of Horace Silver, I can only add one: beauty. His music embodied and exemplified that essential of art. He made the world a more beautiful place.

Steve Elman’s forty-three years in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on WCRB / Classical New England three years. He was jazz and popular music editor of the Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Thank you,after all these years…………I cried reading your comments. I’m a 73 year old piano player heavily influenced by Horace…..we exchanged notes….thank you again. I had just finished playing “Peace” and looked you up in the computer.