Film Review: An Obscure But Fascinating Documentary on the Life of Edith Wharton

Artist/scholar Elizabeth Lennard has managed to evoke the breadth of Edith Wharton’s life and work in a relatively short and vivid film.

Edith Wharton: The Sense of Harmony, a documentary directed Elizabeth Lennard, at the Ninth Annual Berkshire International Film Festival, Lenox, MA., May 29 through June 1.

By Helen Epstein

It’s odd to be writing a review of a fascinating but entirely obscure documentary completed 15 years ago. When Elizabeth Lennard’s 1999 film about Edith Wharton’s life and work was first released, it was neither widely distributed nor seen. I watched it in the former stables of The Mount where it was chosen as part of the Ninth Annual Berkshire International Film Festival that runs in late spring in Pittsfield and Great Barrington.

Wharton’s almost completely restored estate in Lenox, Massachsusetts (See my piece last summer on The Mount and the tour of its grounds) is the perfect place to watch this documentary because it reflects so much of Wharton herself.

Though there are several enhaustive biographies of Wharton and her close friends (including Henry James, Bernard Berenson, and Walter Berry), ample archival photos and plentiful correspondence, it was thought that there was no film footage of the writer. Artist/scholar Lennard has unearthed one and possibly two short clips that show the peripatetic Wharton in motion. But, more important, Lennard has managed to evoke the breadth of Wharton’s life and work in a relatively short and vivid film.

At a time of widespread American provincialism, Wharton, born in 1862, crossed the Atlantic 66 times. She began as a small child, accompanying parents who found it more economical to live in France and Italy after the end of the U.S. Civil War. That early taste of Europe was to her liking and, though she is not associated with one home the way Henry James is, she was almost as much of an ex-pat. In fact, James often accompanied Wharton on trips in Europe and New England. He had his own room at The Mount and regarded Wharton as a “human pendulum” whose automobile was a “chariot of fire.”

Wharton’s homes in New York, Newport, and Lenox, Massachusetts, along with her various dwellings in Paris and the south of France, are seen via early film footage. Most impressive is footage of the first world war, during which Wharton organized women in relief work and even traveled to the front. These clips are complemented by a judicious selection of stills, and accompanied by commentary that draws on Wharton’s own texts, her correspondence (with close-ups of handwriting and stationary), biographies, and criticism.

Lennard has integrated the work into the life, following a thematic — rather than a straight chronological – structure. She loops back to 19th-century Washington Square when discussing novels such as The Custom of the Country and The Age of Innocence and pans over the Fifth Avenue houses owned by the “Lords of Pittsburgh.” We are treated to early clips of street cars, steam ships, the Flatiron building and the Manhattan subway – with New Yorkers appearing as hurried then as now. We see Newport, where her mother and her husband Teddy enjoyed the social life while Wharton retreated to the inner creative space she called her “secret garden.”

In 1908, Wharton’s best-selling The House of Mirth was translated into French and she first moved to the Rue de Varenne in Paris (a plaque now commemorates her stay there) and then to a succession of homes culminating in Hyères in the south of France. But she was always visiting friends elsewhere, including Berenson at I Tatti outside of Florence. We see his gardens and hers, as well as old clips of pre-war Paris and Rome, then wartime France, when Wharton volunteered at home and toured the front with Walter Berry.

And, yes, there are a couple of shots of Morton Fullerton, the dashing and shallow journalist James fixed Wharton up with when she was 45. He was her intro to sexual passion and they had an on-again, off-again affair for just a bit less than three years. In my opinion, Lennard gives Fullerton just the right amount of attention.

Throughout, she relies on a trio of Wharton experts – the late R.W.B. Lewis, Louis Auchincloss, and Eleanor Dwight. All were insightful and passionate about their subject as they were witty and photogenic.

I have rarely been as charmed by a documentary as I was by this one and I can’t imagine why PBS or HBO didn’t snap it up. With any luck Lennard, who lives in Paris, will find a distributor who will make the DVD (which currently can be bought only for $169) available at a reasonable price.

Helen Epstein is an author and journalist whose work is available at Plunkett Lake Press.com

Tagged: Berkshires, Culture Vulture, documentary, Edith Wharton, Elizabeth Lennard, Helen Epstein

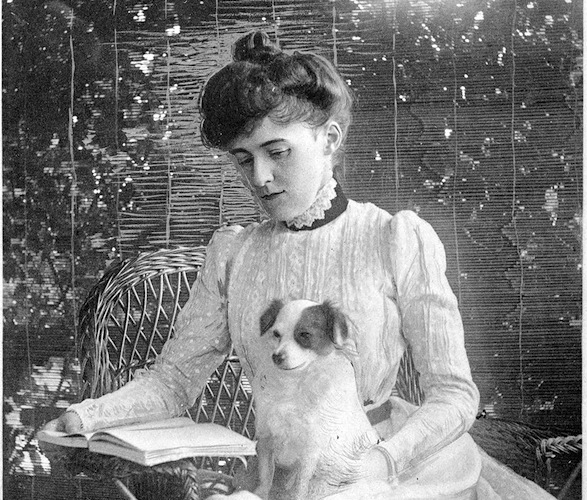

Thank you for this wonderful piece! I love the photograph you chose of Wharton.

And yes, as you say in your article the film has not been widely distributed in the United States. It was co-produced by French national television and was aired there in an even shorter French version, to a wide audience. At that time I believe there was some attempt made to have it aired here, but no one picked it up. It’s a shame!

Next to her novels, what I love most about Wharton is her fearless late-life foray into public service, working for the soldiers.

So far from Henry James.

I just encountered this documentary by chance in Amazon. Exquisite. I will watch it many times, I can already tell.