Fuse Book Interview: James Shapiro on America’s Complicated Relationship With Shakespeare

“There’s no question that Americans have been most drawn to the great tragedies — in our classroom and on our stages.”

By Bill Marx

American writers have had their quibbles with William Shakespeare. “After all, all he did was string together a lot of old, well-known quotations,” quipped H.L. Mencken. James Baldwin, in his 1964 essay, “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare,” confesses that “every writer in the English language, I should imagine, has at some point hated Shakespeare, has turned away from that monstrous achievement with a kind of sick envy.” But Baldwin came around once he realized that his relationship to “the language of Shakespeare revealed itself as nothing less then my relationship to to myself and my past.”

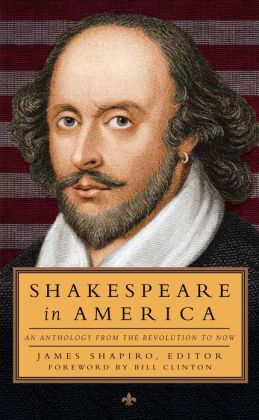

What do Shakespeare’s bonds with America have to say about him and and us? Some (though not all) of the answers to that intriguing question can be to be found in The Library of America’s Shakespeare in America: An Anthology From The Revolution to Now (724 pages, $29.95), edited by James Shapiro. Its publication timed to celebrate Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, the volume is a fascinating, eccentric grab bag of fiction, plays, memoirs, reviews, letters, comedy routines, and song lyrics from a variety of writers and statesmen: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mary Preston, Mark Twain and Delia Bacon, James Thurber and Adrienne Rich, Issac Asimov and Gloria Naylor, John Quincy Adams and Jane Addams. Amid the inevitable chestnuts and eyebrow-raising curios there are some snap-to-attention revelations.

James Shapiro is a Professor of English at Columbia University and the author of a number of books on Elizabethan drama, including Rival Playwrights, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, and Shakespeare and the Jews, the latter a favorite of mine. I e-mailed him a few questions about the anthology, asking why Americans initially took to Shakespearian tragedy rather than comedy and wondering why there were no pieces on the Bard from homegrown playwrights.

Arts Fuse: What did you want to accomplish with this anthology? What you think the volume says about Shakespeare’s importance to America?

James Shapiro: There’s a remarkable body of writing about Shakespeare — by American poets and playwrights, lyricists and humorists, essayists and reviewers — much of it no longer in circulation or little known. My main goal in assembling these great stories is to make them available under one cover, and, through the support of the Library of America, at a very affordable price, so that they can reach a wide readership. I’ll let readers make up their own minds about what these fascinating works of literature reveal about America’s complicated relationship to Shakespeare over the past two centuries.

AF: Isn’t this collection essentially about the mystique of Shakespeare for America? Many of the pieces are more about his symbolic/satiric significance than his literary value.

Shapiro: You can certainly read the volume in that way. Or you could also see it as a story about the kinds of differences we have had in the course of our national history — about race, for example, or who counts as an American — and how writers have turned to Shakespeare to express things not otherwise easily said. I can imagine a dozen other ways to read the collection; that’s the reader’s job; mine was to make this rich material available.

AF: What were some of the pieces in the anthology that you were surprised to discover? Many of the farce versions were new delights to me.

Shapiro: I have been teaching Shakespeare for over thirty years — yet had not encountered many of these wonderful works before. Among my favorites discoveries: Jane Addams on the Pullman Strike in her essay, “A Modern Lear.” And as far as poetry goes, B J Ward’s wry poem, “Daily Grind,” about suburban life and Othello.

AF: Why do you believe that Shakespeare’s initial popularity in America was driven by his tragedies, (particularly Othello) and histories rather than his comedies?

Shapiro: That’s a tough question — one to which I have no easy answer. There’s no question that Americans have been most drawn to the great tragedies — in our classroom and on our stages. And because of the fraught issue of race, Othello remains a central way of engaging issues not otherwise easily addressed. J. Q. Adams’s essay on “The Character of Desdemona” captures all those contradictions and preoccupations. Adams served as our 6th President and was a fierce abolitionist — yet rails against the idea of a white woman falling in love with a black man.

AF: You include Mark Twain’s belief that Shakespeare was not from Stratford. A number of high profile dissenters, such as Charlton Ogborn, have been American. Is there some sort of connection between this doubt about authorship and our enthusiasm for conspiracies?

Shapiro: The authorship controversy should be labelled “Made in America”: Delia Bacon, memorialized by Nathaniel Hawthorne (and anthologized here) was the first to make the case, but not the last, that someone other than Shakespeare wrote the plays attributed to him. The controversy has always been inflected by politics and nationalism. I’ve included a piece — never before published — by another Shakespeare doubter, Mark Twain (who had his own reasons for doubting Shakespeare’s authorship, having to do with his conviction that writers could only write out of their own experience. That may have been true for Twain, though not for Elizabethan playwrights, including Shakespeare).

AF: Some major conflicts about Shakespeare in this country do not appear in the anthology. He has been at the center of the high versus low culture debate. And stage directors have been increasingly ambitious in reinventing (some would say rewriting) the Bard’s plays. Why did you make that choice?

Shapiro: I’d have to disagree, strongly, with you on this one. There are any number of pieces that can only be understood in terms of the highbrow/lowbrow debate — most notably the anonymous account of the Astor Place riot in 1849, when working class New Yorkers protesting a highbrow British production of Macbeth were fired on by the National Guard — with a score killed and over a hundred wounded. If that’s not part of the story of high versus low I’m not sure what is. As for rewriting or reinventing the plays: there’s a great deal of that here as well — from reviews of the Freudian Hamlet staged by John Barrymore to Orson Welles’s anti-fascist Julius Caesar.

Editor James Shapiro — There’s a remarkable body of writing about Shakespeare — by American poets and playwrights, lyricists and humorists, essayists and reviewers — much of it no longer in circulation or little known.

AF: As a theater critic, I must ask why there are so few examples of American stage reviewers evaluating Shakespeare productions. The only postwar review is Mary McCarthy’s terrific look at Macbeth. The others are from movie critics (Pauline Kael and James Agee). And haven’t any American playwrights written on Shakespeare?

Shapiro: I searched far and wide for what some of my favorite playwrights — from Arthur Miller to Tony Kushner — have written about Shakespeare, and came up empty: they engaged Shakespeare in their plays, not, unfortunately, in their criticism or reviews. And again, I have to disagree with you here: As someone who has reviewed and teaches reviewing, I’ve given a great deal of space to reviewers in this anthology: J. M. W. on Cushman, William Winter on Booth, Cather on Antony and Cleopatra, Young on Barrymore, Whipple on Welles, Sillen on Robeson, Alpert on Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar, and Frank Rich on Joe Papp’s Public Theater productions. I too would have loved to include more. But that’s the fate of anyone who attempts an anthology limited to 700 or so pages: those, like you, who are theater critics want more of that; poets want more poetry, novelists wonder why I haven’t included more fiction, and so on. I’m happy with the balance, even if you aren’t, and put together this collection in the hope of reaching as wide a readership as possible.

AF: What do you see as Shakespeare’s future in America? A number of theater directors have publicly speculated that Shakespeare’s language is becoming increasingly difficult for contemporary audiences to understand. Is that a concern to you?

Shapiro: I work with the Public Theater on Shakespeare productions and we recently took a Mobile Shakespeare Much Ado about Nothing into a number of unusual venues, including Rikers Island, New York City’s main jail complex. It was a thrilling experience, and for 90 minutes these inmates were totally absorbed in the play, totally got it. It certainly wasn’t too difficult for them to understand. If Shakespeare is done well — and this burden fall on directors and teachers (who should let students act out scenes from the plays instead of making them study them in rote ways) — there is no significant problem with the challenge of the 400 year old language. So yes.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: anthology, James Shapiro, Library-of-America, Shakespeare

This anthology contains many terrific pieces, but I want to expand on my point above that there is a disappointing lack of offerings touching on contemporary American ideas about Shakespeare. Including period coverage of the 19th century New York riots is all well and good (American dramatist Richard Nelson’s Two Shakespearean Actors is an entertaining 1991 play on the fracas), but suggesting that entries from Mary McCarthy and Frank Rich (debating about Shakespeare with Joseph Papp) seriously reflect the conflict among clashing highbrow/lowbrow approaches to the Bard will not do.

For example, Polish scholar Jan Kott, who wrote the book Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, taught in America from 1969 until his death in 2001. (This year would be Kott’s 100th birthday.) His connection of Shakespeare with Samuel Beckett was an enormous influence (for better and worse) on our playwrights and critics. Not all the contributors to this volume are American – Maurice Evans was British, and to me his piece on editing a “G.I. Hamlet” is one of the least compelling in the anthology. Why not Kott? And there are others in the postwar era, a wide range of American critics and stage directors who wrote about Shakespeare and his significance (in relatively short journalistic pieces) in ways that would have opened the volume more fully to homegrown debates revolving around Shakespeare and Modernism, feminism, ethnicity, and a host of other issues. So I disagree with James Shapiro on this. Perhaps, for the sake of reaching a broad readership, this anthology falls short of doing justice to the “Now” in its subtitle.