Film Review: John Hubley Centennial — America’s Indispensable Designer of Animated Films

That John Hubley was a dominant force in bringing animation out of the studio system and onto the drawing boards of individual artists is well known. What isn’t is how uncannily Hubley’s life story is an entryway into the social history and controversies of mid-20th century America.

By Betsy Sherman

“He always knew there was more to life than Disney and being clever in Hollywood, and he had a very profound feeling about art and literature and music. He always thought there was something beyond, something around the corner, that he was missing.”

–Faith Hubley, interviewed by Patrick McGilligan, in Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist

A compilation of short films made by John Hubley (1914-1977) and Faith Hubley (1924-2001), presented on newly struck 35mm prints for a touring program in honor of the centenary of John’s birth, will visit The Brattle Theater on Tuesday, April 22. That John Hubley was a dominant force in bringing animation out of the studio system and onto the drawing boards of individual artists is well known. What isn’t is how uncannily Hubley’s life story is an entryway into the social history and controversies of mid-20th century America. His trajectory touches on the progressive politics espoused by artists and intellectuals during the 1930s, popular culture’s contribution to the World War II effort, the Red Scare of the late 1940s and 1950s, and the pushback against consumer culture and a notion of “progress” that harms people and the environment.

Born on May 21, 1914 in Marinette, Wisconsin, to an artistic-minded family, Hubley came of age during the Depression. Because of his family’s financial woes, he was sent to live with an uncle in California. He attended art school but left before graduating in order to take a job at Disney. Hubley took part in Walt’s great leap of faith, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, as a background painter. He was a layout artist on subsequent features, including Pinocchio (in fact Hubley wasn’t, in the strict sense, an animator; rather, he was a designer of, and eventually a director of, animated films).

In contrast to the old-timers who had been there at the birth of the Disney studio, the second wave of studio hires, to which Hubley belonged, were at once more aware of the wider art world and less enamored of Uncle Walt’s dictatorial ways. So when an attempt by some at Disney to unionize resulted in a full-on, ultimately unsuccessful, strike in 1941, the pro-union rebels who ended up either quitting or being fired in the wake of the strike tended to be those who craved experimentation in their chosen art form. Three of those ex-Disney animators would go on to form United Productions of America, or UPA, the small, scrappy studio that would change audience expectations of what a seven-minute cartoon could deliver. It was at UPA that Hubley found a home for his artistic vision. But in between Disney and UPA came the war.

Actually, in between being booted from Disney and being wrangled into the war effort, Hubley worked at Screen Gems, the cartoon-making arm of Columbia Pictures. There, with some like-minded colleagues, Hubley was able to distance himself from the “pigs and bunnies” of studios like Disney and Warner Bros., and try out some stylized human characters (for example, in the 1943 Professor Tall and Mr. Small). As opposed to the more accepted round-and-bouncy style, Hubley’s cartoon stars lay flattened against the picture plane, sported Picasso-esque angles, and the perspective is deliberately screwy.

In late 1942, Hubley was drafted into the 18th Air Force Base Unit, or as it became known, the First Motion Picture Unit (FMPU), based in Culver City, California. A supergroup of animators from rival studios worked towards a common goal, crafting training films that would educate members of the armed forces by entertaining them. Hubley worked on the Trigger Joe series, featuring a tail gunner (voiced by Mel Blanc) with whom the average guy could identify. The quick turnaround time of these propaganda pieces encouraged simplification of form and movement, which was something toward which Hubley gravitated (he later refined these principles in a training film made for the Navy, Flat Hatting).

Hubley played a central role in one of the curios of American animation history, the 1944 Hell-Bent for Election. He was hired by the United Auto Workers to design an animated film urging voters to re-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. Collaborating with fellow ex-Disney strikers, and calling in Chuck Jones to direct, Hubley worked at a furious clip to get out the campaign film. In it, two trains race: the modern “Win the War Special,” with an FDR profile on its engine, and the rickety “Defeatest Limited 1928.” The allegory comes off as a mix of Warner Bros. yukfest and snazzily designed taste of postwar animation to come.

The fledgling company that produced Hell-Bent became UPA, and Hubley came on board full-time in late 1945 (by all means check out the DVD boxed set UPA: The Jolly Frolics Collection, and the excellent history When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of an Animation Studio by Adam Abraham). The founders’ stroke of genius was to stop treating the film frame as a proscenium arch. Their contrary stance was that an overall graphic design scheme — in which an abstract background was as important as the characters in the supposed foreground were — could inform and enhance a cartoon’s story and themes.

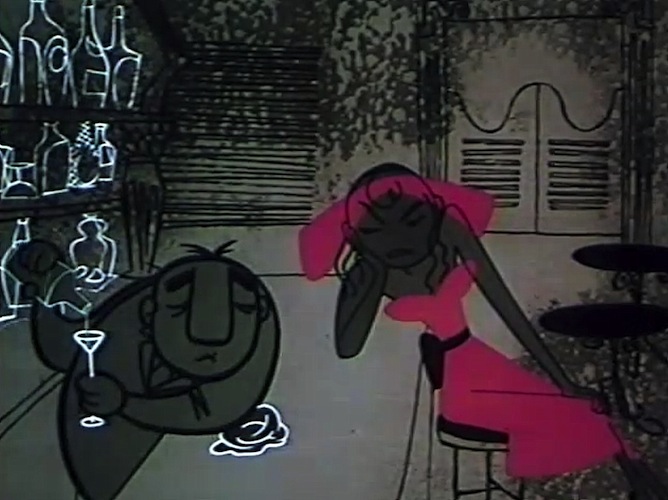

The company took on another project for the UAW, Brotherhood of Man, the aim of which was to convince workers to join racially integrated locals. Then, UPA replaced Screen Gems as the cartoon studio of choice for Columbia. The release that put them on the map was the 1950 Gerald McBoing Boing, about a boy who speaks not in words, but in noises; shunned as a misfit, he finds acceptance emitting sound effects for radio programs. Hubley helped conceive Gerald but didn’t direct it. He tried to top it with the graphically bold Rooty Toot Toot (1951), a jazz-fueled version of the Frankie and Johnny tale.

Internally, UPA had a stormy history, but it was a critic’s darling, and it had a money-maker in Mr. Magoo (first seen in Hubley’s 1949 The Ragtime Bear). External forces conspired to crush the studio and standard-bearer Hubley. The House Committee on Un-American Activities (known as HUAC) had as early as 1947 heard testimony by Walt Disney denouncing the 1941 strikers as Communist subversives (two of UPA’s founders had at one time been party members). The cartoon community wasn’t immune from the name-naming that took place over the course of further hearings during the late ‘40s and early ‘50s (for example, Brotherhood of Man co-writer Ring Lardner, Jr., was one of the Hollywood Ten).

Left-leaning individuals were encouraged to clear their names by testifying; for years, Hubley refused. Columbia put pressure on UPA to clear the ranks of questionable individuals. Several employees signed letters of political repentance, and again Hubley refused. He was fired on May 31, 1952, and blacklisted. Post-UPA, he found a project dear to his heart—an animated adaptation of the Broadway musical Finian’s Rainbow — but after much work had been accomplished, that too was quashed due to an outcry by the cottage industry of “Red”-denouncers. Finally, in 1956, the subpoenaed Hubley appeared before the committee. By that time, he had moved to New York and married Faith Elliott. Hubley invoked the Fifth Amendment; the testimony was not of much consequence. But a corner had been turned: he was through with Hollywood. Faith Hubley, interviewed in Tender Comrades, came to this conclusion: “I think Johnny’s life was made by the blacklist.”

In New York, Hubley opened a studio, Storyboard, and began making animated TV commercials. Dear to Baby Boomers is his creation Marky Maypo, the kid who screams for his hot cereal (the voice is that of son Mark). John and Faith wrote into their wedding vows a pledge to collaborate on at least one personal film a year. And so, along with their abundant body of commissioned work (much seen on Sesame Street and The Electric Company) were all manner of quirky shorts (there’s a live-action anomaly, Date With Dizzy, that has Dizzy Gillespie and his combo being hired by an awestruck adman to score a commercial).

The John Hubley Centennial was put together in conjunction with the Hubley family (which includes animator Emily and Yo La Tengo member Georgia) and contains selections from the years 1956-1970. It begins with the infectious energy of Adventures of an *. The asterisk in the title symbolizes a feisty baby boy who bounces around the screen (propulsion courtesy of a jazz score by Benny Carter, with Lionel Hampton on vibes). His killjoy father becomes a blue blob. Made in the Man in the Gray Flannel Suit era, the cartoon tracks the boy as he conforms, first as a teen, then as a member of the work force — will he become a blob too, or rediscover the dancing asterisk within? A jazz score is also prominent in Tender Game (1958) a watercolor confection set in a Parisian park. Romance is kindled between a doodle of a woman and her male counterpart. Both elation and melancholy are evoked, as Ella Fitzgerald sings, and Oscar Peterson plays with insouciant charm, “Tenderly.”

The Oscar-winning Moonbird (1959) and Windy Day (1967) are imaginative illustrations of non-scripted dialogues between the Hubley children — Mark and Hampy in the former, Emily and Georgia in the latter. The boys have a nocturnal adventure trying to capture the mythical bird; the girls play-act and ponder the future on a breezy summer day. The graphics richly create the ambiance, and the subtle “acting” of the characters makes for hilarious and touching displays of sibling dynamics.

The remaining titles deal with political, social and environmental issues that still figure into the global conversation. The Hat (1964) is the Cold War reduced to Becket-style absurdity, with two soldiers needling each other from either side of a demarcation line. The voices are Dizzy Gillespie and Dudley Moore, then known only as a member of the Beyond the Fringe troupe. Both Urbanissimo (1966) and Of Men and Demons (1968) ponder the cost of industrialization, the latter using myth (pointing towards the non-Western traditions Faith would explore in her solo work). Eggs (1970), with ham-fisted ribaldry, frets about overpopulation. Its voluptuous fertility goddess is countered by a wise-cracking death figure — somehow, it comes off like the filmmakers are both against and for rampant breeding.

It’s a worthy centennial celebration, and I hope to see the same for Faith Hubley ten years from now.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.