CD Reviews: BMOP plays Babbitt and Antheil (BMOP/Sound), and Chris Wild’s Abhanden (Navona Records)

Snappy new recordings of the music of Milton Babbitt and George Antheil from the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, while cellist Christ Wild’s disc offers a fascinating journey through some richly diverse musical soundscapes.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

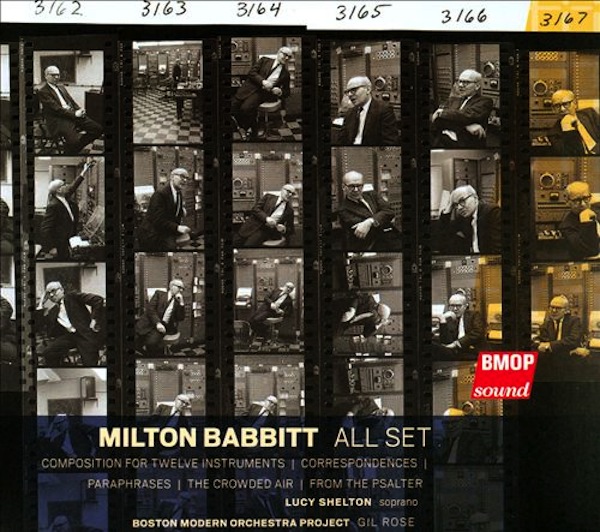

Love him or hate him, Milton Babbitt remains one of the most important figures in post-World War 2 contemporary music. Remarkably, that reputation is built more on his polemical writings than his music: only a small number of his works are performed with any frequency (though a couple, notably Philomel, are classics in their respective genres). Part of the reason for this is that his music is so fearsomely difficult to perform with any degree of accuracy that the number of musicians inclined to devote the number of hours to rehearse and render such labyrinthine scores is excruciatingly small.

Thank goodness for the Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP) and Gil Rose, then. All Set, the orchestra’s first all-Babbitt disc, demonstrates not just boatloads of technical rigor and attention to detail, but just how musical and – yes – inviting Babbitt’s music, well played, can be.

The six works included on the album span more than five decades, beginning with the Composition for Twelve Instruments, Babbitt’s first major total serial composition (written in 1948) and ending with From the Psalter, his 2002 setting of three biblical psalms. On all six works, BMOP sounds to be in particularly fine form: the sonics on this album are not only vibrant and clear but also finely balanced, and the ensemble plays with discernable concentration and energy.

What is perhaps most impressive about this disc, though, is the insistent musicality of Babbitt’s musical language. There’s a firm sense of musical drama, as demonstrated in the Composition for Twelve Instruments, which begins with shards of seemingly random sounds gradually coalescing around an harmonic core. Babbitt’s legendary sense of humor is on full display in the witty All Set, an essay in jazz and serialism that suggests that the stylings of Bill Evans and Thelonious Monk were not, perhaps, that far removed from the world of the postwar avant-garde.

Above all, there’s a remarkable amount of beauty in this music. The longest work, 1979’s chamber score Paraphrases, revels in subdued instrumental color. Though it certainly sounds at times like a product of 1960s electronica (which it is), the notoriously tricky tape-and-strings piece Correspondences draws beguiling, pointillist timbral shapes. And the later pieces, The Crowded Air and From the Psalter (here featuring the timeless, excellent soprano Lucy Shelton), indulge in swooning, lyrical writing.

It all adds up to a compelling and highly satisfying account of music by one of the most notorious composers this country has produced.

*****

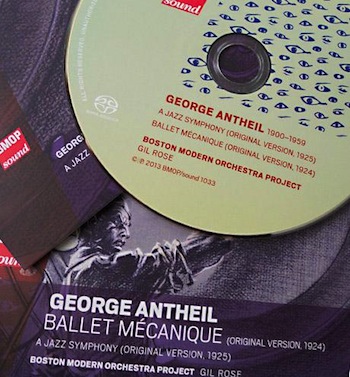

Sheer, unadulterated fun isn’t a phrase often used to describe classical music – new or old – but it’s the one that kept popping into my head listening to BMOP’s new all-George Antheil disc, featuring the raucous A Jazz Symphony and earth-shaking Ballet Mécanique. Both pieces date from that magnificently outlandish decade, the 1920s, and they’re overflowing with the excitement and limitless enthusiasm of the age, not to mention a little nose-thumbing provocation here and there.

Though not widely known today, Antheil was the enfant-terrible of mid-‘20s Paris, composing “ultra-modern” music that often provoked violent reactions from post-World War 1 audiences. It’s not hard to see why after about the first minute of Ballet Mécanique, a 25-minute long aural assault that consists of thunderous noise for most of its first twenty minutes that, over its last five, is punctuated by outbursts of silence. Roll over, Beethoven, indeed.

In addition to a large orchestra, Antheil had originally included sixteen pianolas (a sort of player piano) in his score, but practical limitations meant that he had to reduce the number to one – the technology of the ‘20s made synchronization of more than one instrument virtually impossible. BMOP’s recording uses eight Disklaviers (the most that could be fit onto the Jordan Hall stage) controlled by a Nintendo Wiimote and the effect here is staggering: think of Stravinsky’s Les Noces crossed with the Rite of Spring and Edgard Varese’s Amériques. Bedlam never sounded as good as it does in the hands of Rose and BMOP.

A bit more subdued is A Jazz Symphony. Written for Paul Whiteman’s second “Experiment in Modern Music” (the first one had debuted Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue), it was premiered not by Whiteman’s band, but by the orchestra of the great jazz/bluesman W. C. Handy. The piece is a wacky hodge-podge of quotes and references: there’s lots of syncopated music that sounds like Scott Joplin, Stravinsky, and Gershwin; suggestions of popular songs of the day; some manic solo piano writing; and a big waltz (of all things!).

It’s loads of fun and BMOP plays like they’re having a blast with it. John Damian’s banjo solos bring the welcome flavor of authentic, African-American jazz to the proceedings, while Nina Ferrigno and Geoffrey Burleson manage the wild keyboard parts with great character. Equally excellent are principal trumpet Terry Everson’s gutsy solos, and the superb percussion work of Robert Schulz and Craig McNutt.

*****

While the title of cellist Chris Wild’s new recording on Navona Records, Abhanden, evokes Mahler, its content features, enticingly, only music written in the last forty years. In addition to two solo works, members from the Chicago-based Ensemble Dal Niente join him in what proves to be a fascinating journey through some richly diverse musical soundscapes.

Chinary Ung’s Spiral (for cello, piano, and percussion) makes for an ear-catching opener, filled with both potent musical drama and a rich palate of instrumental color. It’s features many cross-cultural references – the music seems to evoke Ung’s native Cambodia as much as it embraces more Western-sounding gestures – and, at fourteen minutes, sometimes feels a bit long for its content. But Wild’s performance, in which pianist Mabel Kwan and percussionist Greg Beyer join him, is gripping, filled with charm and pathos.

Equally engaging, but for different reasons, is Claude Vivier’s Piece pour violoncelle et piano. Written in 1975, it’s an ominous work, alternating violent, tremolo sections with more lyrical passages. Both “styles” impinge on one another, and the overriding affect is a kind of tense beauty. Wild’s playing here is very physical and ethereal, sometimes at once: there’s an introspective focus to his playing in the songful sections that corresponds powerfully to the music’s aggressive passages.

The middle three pieces – Daniel Dehaan’s If it encounters the animal, if it becomes animalized; Andrew Greenwald’s Jeku (II); and Marcos Balter’s Memória – share a fascination with sound, timbre, and gesture. Taken individually, each piece has striking moments: the spectra of harmonics flickering throughout Memória is especially haunting and Dehaan’s writing includes various extended techniques for the bow hand that create all sorts of unexpected sounds.

But, together, the three works succumb to the problem that, generally, plagues most music that’s primarily based on gesture and effect, namely, they all sound more or less like the same piece. None of them demonstrate either the sense of latent musical drama found in the Vivier and Ung scores or – perhaps more crucially – any musical ideas that make them stand out in a distinct, memorable way. It’s rather a pity, since Wild’s performances are first-rate.

More satisfying is the closing track, Eliza Brown’s Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen. Brown sets the same Rückert poem that Mahler did, though she comes at it from a completely different perspective (save the first three notes of the vocal line), with a piece for voice, cello, and electronics. Amanda DeBoer Bartlett’s sweet soprano floats over a jagged, otherworldly aural topography, and Wild’s account of the cello part is, by turns, irascible, savage, and serene.

Throughout, the audio quality is excellently balanced and the performances are impeccable. In addition to his aforementioned collaborators, Wild is joined by the daring, capable violinist J. Austin Wulliman in Jeku (II).

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: A Jazz Symphony, Abhanden, All Set, BMOP, Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Chris Wild, George Antheil, Milton Babbitt