Book Review: Playing in the Shadows of the Modernist Giants

The wily Enrique Vila-Matas remains wary but respectful of Ernest Hemingway and asserts his independence by going on his own self-consciously vaudevillian way—Juan Gabriel Vásquez is too subservient to elude the shadow of Joseph Conrad.

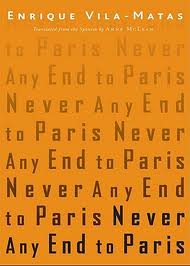

Never Any End to Paris by Enrique Vila-Matas. Translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean. New Directions, 208 pages, $15.95.

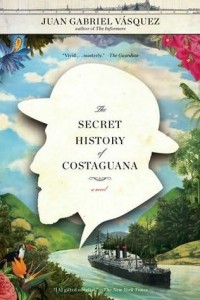

The Secret History of Costaguana by Juan Gabriel Vásquez. Translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean. Riverhead Books, 283 pages, $26.95.

By Bill Marx

Both of these entertaining books poke at Modernism from the cultural margins, mixing fiction and nonfiction to fudge boundaries, rethink the past, undercut aesthetic platitudes, and pay dutiful if clear-eyed homage to genius. The perch on the periphery lends the volumes the freedom to poke at literary brand names from unexpected and illuminating angles, but it also encourages playing it safe—they are a little too content to sit on the cusp.

Celebrated Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas’s fictionalized memoir of his years (the mid-1970s) as a young writer in Paris toasts and at times impishly roasts Ernest Hemingway and his A Movable Feast. Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s novel imagines the tragic life story of a Latin American whom Joseph Conrad interviewed for background for his 1904 masterpiece Nostromo. On the day Conrad dies, the lost soul feels free to confess that the latter’s fictionalized country, Costaguana, distorts the barbarity in Panama he told the novelist about. Both Vila-Matas and Vásquez question (albeit paradoxically) whether fiction is the lie that tells the truth.

The volumes also share the same superb translator, Anne McLean, who manages to catch the different authorial tones with aplomb. Vila-Matas’ Never Any End to Paris is playful and personal, a fragmented portrait of the artist as an aging and undependable yarn spinner, a whimsical narrator who is perhaps a little too afraid of committing the uncool sin of nostalgia.

Talkative, meditative, gossipy, offering words of wisdom on creativity as well as quotations from the worthies (“Having lived in Paris unfits you for living anywhere, including Paris.” John Ashbery), the reminiscence expends much self-conscious energy to cover up the essential conventionality of its fable—the evolution of the writer from a shallow innocent who prizes alienation as a sign of authenticity to a more mature sensibility that values the power of the prosaic. One more time, the youthful appeal of poetry (and unrecognized genius) must be rejected so that “the vulgarity of narrative” can be accepted. Thus Vila-Matas’ affectionately sardonic, deliciously skewed view of Paris as the perpetual symbol of artistic promise—there’s never any end to it (the title comes from Hemingway) because each generation must be awakened from the city’s seductive mystique.

Presented to the reader as a skittish lecture about his youthful days in Paris, the meta-fictional reminiscence skips about, sometimes referring to Vila-Matas’s recent visits to the city (during a fight in a club he claims his wife punched him and took out two of his teeth), sometimes dwelling on his gloomy days penning what he says is his first novel (The Lettered Assassin) while living in a room rented out by Marguerite Duras, who lived below. Yet in “real life” the writer was more accomplished during his time in France than he claims—The Lettered Assassin was his second book (published in 1977), and he had already directed a couple of films. Mixed into this readjustment of reality are interesting reflections, biographical and philosophical, on Hemingway’s Paris, the nature of the artist, the delusive attractions of of despair, and the relationship between elegance and happiness (“I discovered how inelegant it is to walk, sad, in despair, dead, through the streets of your neighborhood in Paris” ).

All of this proffers much literate pleasure, with glimpses of Samuel Beckett and other famed artists, amusing episodes, including a party in which Vila-Matas is stunned into silence by the beauty of the young Isabelle Adjani, and at times poignant revelations, especially the compelling portrait of the eccentric Duras, flush with the success of her film India Song but bedeviled by the dawning realization that she had run out of things to write about.

Unfortunately, the book’s concrete evocation of time and place, of 1970s love of rock and roll, underground movies, and experimental fiction is marred by Vila-Matas need to proclaim his wised-up credentials from time to time. It is as if he has to flash a spoilsport, post-modern police badge to curb our enjoyment, especially about how he needs to be ironic, to distance himself from the facts, to invent himself as a “character” in order to reach the truth. Thus he tosses in the Ashbery quotation (and others) to make sure no one falls for sentimental, Hemingway-esque snake oil. “After all, to be ironic is to absent oneself,” he intones at one point. Well, not really—Vila-Matas is never more irritatingly present than when he is telling us how ironic he must be for his and our own good.

The least convincing part of Never Any End To Paris is when Vila-Matas wants us to admire (ironically?) how deeply he admires writers who “speak their minds,” concluding that those who “lay it on the line, only they seem to me to be true writers.” Overlook this polished preening and the book presents an endearing evocation of the writer’s feelings about Paris, his meditations on fiction then and now, self-dramatizations of the ups-and-downs of the authorial life (“scenes of mystery, disturbance, and jealously”), its fleeting sexual interludes, its warm friendships and creative rivalries. And the volume’s brief depiction of Duras’ meltdown provides a memorably chilling note of mortality.

Vila-Matas generally rules politics out in his look back, but historical tragedy propels Vásquez’s The Secret History of Costaguana, which touches on centuries of social chaos and revolutionary slaughter in Colombia, focusing on the bloody machinations surrounding the building of the Panama Canal, a mishmash of violence, delusion, and greed supported by the imperialist powers, first France and then America. Through the trials and tribulations of Jose Altramirano, Vásquez doesn’t want to supplant or accuse Conrad (he’s no Chinua Achebe taking on Heart of Darkness, which might have made for a more exciting storyline), but to augment Nostromo‘s perceptive vision of a failed Latin America, which Conrad saw as caught in a vicious tangle of internal conflicts between indolent, aristocratic liberals and destitute, volatile masses—and the intrusion of external, imperialist, domineering foreign capital.

Conrad saw foreign investment as a paradox—benevolent, even idealistic good intentions that end up serving corrupt local interests. In The Secret History of Costaguana Vásquez presents a far more malignant picture of imperial powers handily exploiting a hapless country whose endemic weakness for discord aids and abets its own economic victimization. One of the narrator’s principle metaphors for the misery of Colombia, and its loss of Panama to the United States, is disease: “For there, in the Isthmus of Panama, the colonial spirit floated in the air, like tuberculosis. Or maybe, it occurred to me at some point, Colombia had never stopped being a colony, and time and politics simply swapped on colonizer for another. For the colony, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.” The novel’s view of Colombian history (“meddling, despotic, murderous”) is of a cyclical, black comedy, a lethal back and forth of ham-fisted liberal and conservative governments, interludes of exhausted moderation interrupted by a return to authoritarian heavy-handedness, a national sense of inferiority encouraging the scuttling of genuine efforts at establishing freedom and independence.

This notion of politics as sardonic farce tweaks Conrad’s grand earnestness, but that’s about all, and Vasquez’s tragicomic tone undercuts his efforts at substantial characterization. Jose is the son of a journalist who unconsciously propagandizes for the French construction of the canal, his life ending in disgrace when the effort to build the canal ends horribly, with accusations of financial wheeler-dealing blackening reputations. The anguished Jose carries on the shameful tradition, helping Colombia’s enemies when the Thousand Days’ War (1899–1902) breaks out, making it easier for the United States to secure Panama and the canal route through bribery.

But Jose is not much more than an idea dramatizing crucifixion and predictably flummoxed expiation (a betrayer betrayed by art and country), and some of the novel’s sections, which speculate about Conrad’s life as a seaman, even theorizing that he might have tried to commit suicide at one low point in his career, feel more like bad ideas left over in Vásquez’s mind after he penned a biography of Conrad in 2003.

Still, McLean’s translation maintains the jaunty angst of the narrator’s tone, and Vasquez remains an intriguing, easy-to-take writer, though this book, like his first novel The Informers, serves up warmed over tropes of Latin American perfidy rather than fresh revelations. The wily Vila-Matas remains wary but respectful of Hemingway (in an interview he says Hemingway is not one of his favorites) and asserts his independence by going on his self-conscious way—Vásquez is too subservient to escape the shadow of Conrad.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Anne McLean, Enrique Vila-Matas, Hemmingway, Never Any End to Paris, New-Directions, Paris, Spanish, fiction