Book Interview: Jay Wexler on the State of “Our Non-Christian Nation”

By Blake Maddux

The book deals with how Atheists, Wiccans, Summums, Muslims, and Satanists “fought to have their voices heard” in communities dominated by Christians and others who were skeptical of their claim that the First Amendment applies equally to all religions.

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, an elementary school in Peabody, MA, included two students who grew up to practice the art of professional humor in sharply distinct fashions and to significantly varying degrees.

One would become a stand-up comedian whose forthcoming HBO comedy special The Great Depresh will premiere on October 5. Comedy fans know him as Gary Gulman. The other would graduate from Harvard, the University of Chicago Divinity School, and Stanford Law before clerking for Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, working at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel, and becoming a tenured law professor at Boston University. His name is Jay D. Wexler.

How, you ask, does the latter individual qualify as a professional humorist? Well, among Professor Wexler’s six books are two works of humorous fiction about a character of his own creation, Ed Tuttle, Associate Justice. In 2005, he conducted a study of the frequency with which Supreme Court Justices provoke laughter from spectators. The New York Times’ Supreme Court reporter, Adam Liptak, wrote about the study in a piece that appeared on the presumably not-yet failing newspaper’s front page. (Click here for the subsequent history of the three-page article that its author describes as “the gift that keeps on giving.”)

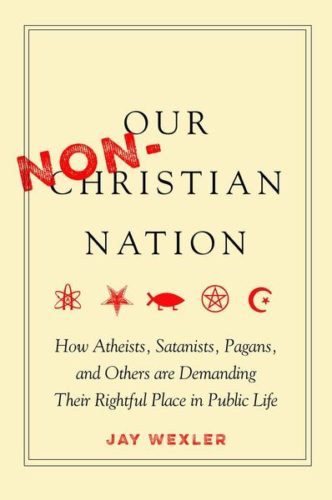

Wexler’s latest book is Our Non-Christian Nation: How Atheists, Satanists, Pagans, and Others Are Demanding Their Rightful Place in Public Life (Redwood Press, Stanford University). In it, he describes episodes in which Atheists, Wiccans, Summums, Muslims, and Satanists “fought to have their voices heard” in communities dominated by Christians and others who were skeptical of their claim that the First Amendment applies equally to all religions.

Professor Wexler, whose Twitter handle is @SCOTUSHUMOR, spoke by phone to The Arts Fuse in advance of his reading at Harvard Book Store on Friday, September 13.

The Arts Fuse: Is Our Non-Christian Nation to any extent a follow-up to your first book, Holy Hullabaloos?

Jay Wexler: I view it as kind of a sequel. This was a concern for my editors. They didn’t want it to be viewed as the same book, basically, and I don’t think it’s the same book. The analogy I used to explain it to them was that Holy Hullabaloos was kind of like an introductory survey course to law and religion and church-state law, and Our Non-Christian Nation is kind of like an advanced seminar that focuses on one part of it. It’s the same professor and it’s got a lot of the same themes, but it’s on a much more specific subtopic under the broad umbrella of church-state studies, which is what Holy Hullabaloos was about.

AF: In the Introduction, you describe the United States as being both “post-separatist” and “increasingly non-Christian.” What is the significance of these two seemingly opposing forces being at work simultaneously?

JW: Those are the two kind of straightforward observations that basically made the book come together for me. Those two things are interesting because it puts nonbelievers increasingly in the situation of having to figure out what to do now that they’ve kind of lost the separation battle. So the idea of partaking in public life is not an easy or a typical one for non-Christians because usually the reaction to how government and religion should interact for minorities is not at all. They should be kept quite a bit separate because that’s the way that’s most protective of minority faiths. But now that those battles have been lost, not entirely but in large part, I think it’s time to sort of reevaluate whether that’s the right thing to do. It’s really interesting to me, the combination of those two phenomenon.

AF: You also declare that “the Supreme Court has already rejected the possibility of a secular public square.” Has it as clearly rejected the possibility of a uniformly Christian public square?

JW: Not as clearly, no. There are decisions that come up because there are Christians involved. So most of the cases do involve Christians, and when the Court has said that the government can be open to religion, it usually happens to be cases involving Christianity. It has not really heard too many cases about the kind of things I write about in the book. One could point to the Ten Commandments as being an example of how the Court is actually promoting a Christian public square because the Ten Commandments is clearly a religious symbol and the Court said it was okay. But they’ve also in some cases, like the Town of Greece [v. Galloway] case, the legislative prayer case, said that government can’t discriminate on the basis of religion when it’s inviting people to give the opening prayers. So although the Court hasn’t said it, necessarily, I think it has kind of endorsed a public square that can be used by religions of all kinds and not just Christianity.

AF: Wouldn’t endorsing a wholly secular public square be a way of treating all religions equally?

JW: Yeah, that’s exactly right. And that’s why minority religions prefer it, because it makes it so that the government can’t support any particular religion. In fact, the particular religion that usually gets support is Christianity. That’s why traditionally minorities have wanted there to be a completely or mostly secular square so that the government’s not supporting any religion at all and then everybody’s treated equally. The problem is that the Court just doesn’t buy that, and has said that we don’t need to have a completely secular public square under the Establishment Clause. Christians have taken advantage of those cases and now it’s up to the religious minorities to participate alongside them. That’s the point that I’m trying to make.

AF: Christians and the government are sometimes, in your words, “willing to exclude religion entirely from some public space rather than allow Christianity to share the stage with other religions and nonreligious views.” Doesn’t that work against Christians by making the public square more secular?

JW: This is ironic, I think, that it’s possible that the demands by religious minorities to partake in public life alongside Christians will have the effect of creating a secular public square if the Christian majority decides that it doesn’t want to share the stage. That usually doesn’t happen unless the Satanists are involved. When the Satanists are involved, what’s happened several times is that the government says, yikes, we can’t have a Satanist give an invocation or circulate their materials to children in the public schools, even if the Christians are also doing that. So it’s better to have no religion rather than having Christianity and Satanism doing their thing in public. That’s one of the great things about The Satanic Temple. They make people face the implications of what they say they believe in. Christians will say, we believe that religion should be in public and we believe in religious pluralism, sure. But then the Satanists come and they are not so sure anymore! So it’s interesting.

Author Jay Wexler — The Supreme Court has kind of endorsed a public square that can be used by religions of all kinds and not just Christianity.

AF: Why should skeptics give The Satanic Temple the benefit of the doubt and why should Christians not fret about its motives?

JW: I think people ought to try to understand what The Satanic Temple is about before they start criticizing them. It’s true that they have appropriated, in a sense, a symbol that is part of the Christian tradition, but they’ve made it their own and it doesn’t have the same meaning to them as it might have to a traditional conservative Christian. I think that if anyone were to look at The Satanic Temple’s seven tenets, which are right there on their website, they would see that this is not a group that’s into child sacrifice or eating cats. The ideas of venerating Satan as a symbol of opposition to authority and oppressive domination by the majority is something that goes back to the 17th century, mostly in literature rather than religious practice. So it’s not like they made it up. The problem is that Satan also has this media-driven meaning that comes from the ’70s and The Exorcist and The Omen and people complaining about Dungeons & Dragons. So they have this knee-jerk reaction, believing that anybody who calls themselves a Satanist must be an evil person. But there’s nothing about The Satanic Temple that’s evil. Becoming familiar with them should be sufficient for people to understand that.

AF: And The Satanic Temple is not a parody group or a gadfly out to just cause trouble.

JW: It’s part of what they do, of course, and that’s not surprising given that Satan is kind of a trickster, in a sense. I can understand why people might think, oh, they’re trolls who are making this stuff up to just to piss people off. But I try to explain in the book, because I think it’s a really misunderstood point, that The Satanic Temple does many more things than just that. It’s a genuine religious community, which has fellowship, ethical beliefs, rituals, and everything else most religions have. I think the Flying Spaghetti Monster is more likely to be a parody group than The Satanic Temple.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

Tagged: Atheists, Blake Maddux, Our Non-Christian Nation, Our Non-Christian Nation: How Atheists, Pagans, Redwood Press