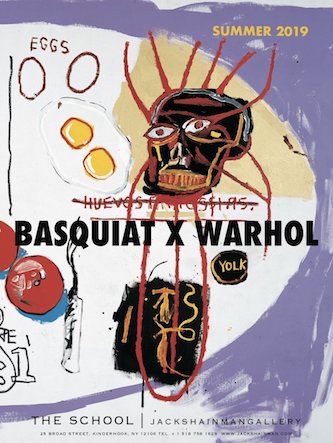

Visual Arts Review: Jack Shainman Gallery: The School — “Basquiat x Warhol”

By Charles Giuliano

Perhaps this review is an autopsy for which I offer an apology.

Basquiat x Warhol at Jack Shainman Gallery: The School, Kinderhook, NY, through September 7

Jean-Michel Basquiat, “Untitled (Football Helmet),” c. 1981–84. Courtesy of Shainman Gallery.

The New York gallerist Jack Shainman grew up in Williamstown, MA, where he visits each summer. Five years ago, in Kinderhook, New York, he opened a gallery/ museum called The School. It is open on Saturdays through early September. On a glorious day we navigated country roads from North Adams, Massachusetts.

I have covered Shainman since he started in Provincetown decades ago. In the city we always visit the gallery. His partner, Claude Simard, passed away in 2014. There is a small, poignant memorial to the French Canadian artist/gallerist in The School. Simard was a frequent traveler in Africa and India and was seminal to the gallery representing major African and African American artists.

For the current season The School features Basquiat x Warhol, a show of collaborative (and controversial) works by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) and Andy Warhol (1928–1987). Their bromance ended after a vicious, September 20, 1985 New York Times review by Vivien Raynor. She wrote that Basquiat was “doing a pas de deux with Andy Warhol, a mentor who assisted in his rise to fame. Actually, it’s a version of the Oedipus story: Warhol, one of Pop’s pops, paints, say, General Electric’s logo, a New York Post headline or his own image of dentures; his 25-year-old protégé adds to or subtracts from it with his more or less expressionistic imagery. The 16 results – all ‘Untitleds,’ of course – are large, bright, messy, full of private jokes and inconclusive. . . . the collaboration looks like one of Warhol’s manipulations, which increasingly seem based on the Mencken theory about nobody going broke underestimating the public’s intelligence. Basquiat, meanwhile, comes across as the all too willing accessory.”

Basquiat first appears in Warhol’s Diaries on Monday, October 4, 1982. “He’s just one of those kids who drives me crazy . . . and then Bruno [Bischofberger] discovered him and now he’s on Easy Street. . . . had lunch for them and then I took a Polaroid and he went home and within two hours a painting was back, still wet, of him and me together.”

Their cobra/ mongoose relationship has invited endless and often unkind speculation. Creatively, Warhol was on a downward spiral. Abandoning The Factory as too dangerous, after being shot by Valerie Solanas (June 3, 1968), he opted to hang with VIPs at Studio 54. He cashed in by making formulaic celebrity portraits.

Despite being shunned by MoMA, The Whitney Museum, and the mainstream art world, Basquiat was on the upswing. Galleries found his graffiti art desirable and very salable. Notoriously, dealers like Annina Nosei, Bischofberger, and Tony Shafrazi fueled his work with mountains of cocaine and smack. He stuffed the pockets of his paint-spattered designer suits with wads of cash.

It was all trashy, tragic, and outré, symptomatic of the kind of bohemian chic that fuels market-making major museum extravaganzas — and this intriguing rural sidebar in Kinderhook.

The jury is out as to who got the upper hand in their fraught, symbiotic relationship. In PR for their 1985 Shafrazi show the artists were depicted as boxers going toe-to-toe. It’s said that Basquiat got the TKO, although the media presented him as a Warhol mascot.

Race was key to their differences. The son of a middle class Haitian father and mentally disturbed Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat was disowned at an early age. Against all odds, posthumously, he became the most acclaimed artist of his generation. His too brief life, however, was beset by addiction and discrimination. Following an OD, he left a thousand paintings and ten times that number of drawings.

Entering The School evokes an immediate compare and contrast between the artists. Straight ahead is Warhol’s witty, camouflage self portrait. A master of pop marketing, he sold himself as a logo.

The first work we encounter by Basquiat couldn’t be more funky. An act of voodoo panache, nappy hair was pasted on top of a hand-painted football helmet. He asked Warhol to wear it for a day to see how it feels to walk around as a black man in racist America. It’s likely that campy Warhol, the King of Pop, missed the point. But Basquiat had a mojo that Warhol craved. The wigged-one sank his fangs into that fresh young blood.

Warhol collaborated with Franceso Clemente, but focused on Basquiat. He also hung out with Keith Haring and other graffiti artists.

The School is oddly configured. We are diverted into a corridor that winds around until we find the main gallery and encounter the Minotaur. We follow the thread of Basquiat’s magic marker on plates. The series includes 45 homages to artists and individuals he admired. With wicked wit, Warhol’s plate is inscribed “Boy Genius.”

Gallery with works by Andy Warhol. Courtesy of Shainman Gallery.

One plate simply states “Cimabue.” It succinctly references the Italian Gothic painter. An autodidact, Basquiat displayed an encyclopedic curiosity, his interests ranging from anatomy and science to cartoons, sports, and jazz. As a jazz fan, I love when he lists the tracks on famous albums. We found titles from a Duke Ellington LP.

There is a rough and smooth sensibility to this show. Warhol at his best is glib, inventive, and hip. He extracted details from erotic Polaroids and created silkscreen paintings. There is a room of penis images.

The epic Warhol is a huge “Last Supper” in black and white. It’s on the scale of Leonardo’s — but features superimposed logos.

For this exhibit The School borrowed from private collections. There is a heady mix of major and minor works as well as videos. Unfamiliar aspects, more peripheral than iconic, of the pieces here prompt reevaluation of the vast oeuvre of both artists.

The room of collaborative paintings leaves me feeling mixed. The best works — when Basquiat cancelled and obliterated the contributions of Warhol — are missing. Andy never seems to have come up with an adequate counter punch.

The death of Warhol, of complications recovering from routine surgery, devastated Basquiat. Bad habits grew worse. Their demise within a year of each other haunts this exhibition. Perhaps this review is an autopsy for which I offer an apology.

The sixth book by Charles Giuliano, Counterculture in Boston: 1968 to 1980s, will be published this summer with Boston Fine Arts: Museums, Galleries and Artists to follow.

Tagged: Andy-Warhol, Charles Giuliano, Jack Shainman, Jack Shainman Gallery: The School