Visual Arts Review: “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth” — Treasures of an Imaginary World

By Clea Simon

This is the most extensive public display of original J.R.R. Tolkien material for several generations.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth at the Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Ave., New York, NY, through May 12.

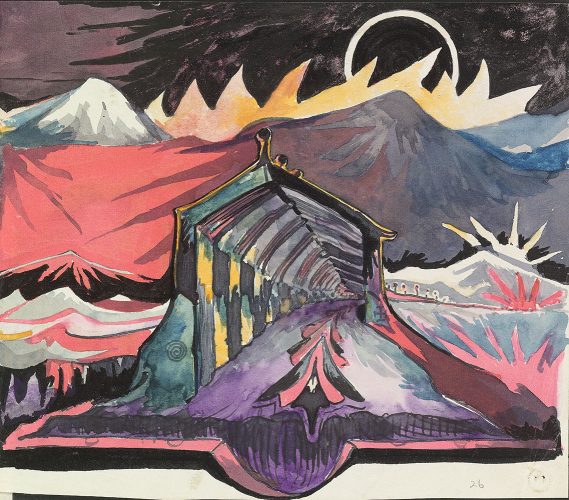

J. R. R. Tolkien, “Fantasy landscape,” 1915?, watercolor, black ink. Photo: The Tolkien Trust.

Before 2001, the world was divided into two parts. There were those of us who read the works of J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973), and then there were the rest. Until that year, when Peter Jackson’s hugely successful film version of The Fellowship of the Rings – the first film of his three-part adaptation of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy – was released, those of us who loved Hobbit lore, who could recall the alliances of the last battle and recite Malbeth the Seer’s words, were a self-selected and, at times, secretive bunch: grown adults still entranced by a “kids book.” Devotees of a 1,000-plus page fantasy epic written more than half a century ago. Rune readers who understood the importance of riddles. Ring wraiths in our own way, with a little core of obsession hidden deep within.

Jackson’s movie versions changed all that, adding humor and more active female roles while bringing this quest tale to a broader audience. However, it is those of us who loved – still love – the books, the ones who can speak Elvish or find Weathertop on a map, who will get the most out of the Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth, a small-scale but groundbreaking exhibit on display at the Morgan Library.

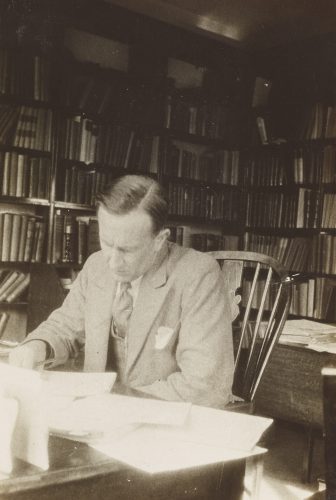

J.R.R. Tolkien in his study, ca. 1937, black and white photograph. Photo: Tolkien Trust.

It’s debatable how The Lord of the Rings, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s masterpiece, would do if published today. By any standard, its language is formal, elegiac, and old-fashioned. To many it must read as stilted or overly ornate, though it has become the template for most fantasy fiction since its 1954 publication. But language is culture, and in Tolkien’s world words are beautifully distinct, defining and delineating the creatures who inhabit his books, from the guttural “black tongue” of Mordor’s orcs (itself derived from a kind of ruined Elvish) to the booming vowels of the Ents. In a series of rooms, and by way of its excellent curatorial notes, the Morgan exhibit explores the roots of those languages – that world – displaying material from Bodleian Library’s Tolkien archive at Oxford as well as pieces from the Marquette University Libraries and private collectors, in what is billed as the most extensive public display of original Tolkien material for several generations.

Tolkien was a philologist, studying and then teaching everything from German philology – the structure as well as the historical development of the language – through Old Norse, Old Icelandic, and medieval Welsh. When he returned to his alma mater, Oxford, after years at the University of Leeds (and the trenches of World War I, but more on that in a bit), he did so as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo Saxon. His life there, with his beloved Edith (whom he had courted as a teenager), is recalled here in photos as well as writings that reveal his devotion to his family, such as the illustrated letters from Father Christmas that he created for their four children, down to the “stamps” from the North Pole.

For Tolkien, as the Morgan exhibit shows, had been imagining worlds visually as well as linguistically long before he began mapping out Middle-Earth (Tolkien’s punctuation). Early drawings and watercolors of both real and imagined landscapes reveal a fascination with “faerie” and the love of nature that would inform his fiction. His dream was a peaceful, green land – an archetypal England. And although this longing can be seen in his surprisingly graceful youthful efforts, it was certainly heightened by his experience in the trenches of World War I. (Tolkien was invalided out in November 1916, after less than six months in France, which probably saved his life. He would later write, “By 1918, all but one of my close friends was dead.”) Throughout that period he was writing and drawing. And, if the Morgan has a few too many of his newspaper-margin doodles on display, it also chronicles how these efforts come together in the creation of alphabets and runes with their own cohesive internal structures and history.

These, of course, first came to the public’s attention with the publication of The Hobbit, and the exhibit has a wealth of material, including correspondence and artwork for the original 1937 Allen and Unwin edition. But the true treasures of this show relate to what came next – The Lord of the Rings and beyond.

J. R. R. Tolkien, “The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the Water,” August 1937, watercolor, white body color, black ink. Photo: The Tolkien Estate.

Originally conceived as a sequel to The Hobbit, the trilogy took 12 years to write and grew to encompass much of what the Oxford don had learned of war and the brotherhood of the trenches, as well as philology. It was also the most successful public presentation of the exhaustively imagined world that Tolkien spent his life creating. Timelines, at points broken down to day by day, chart out where various characters are, while maps and illustrations – many of which have not made it into the books – reveal how thoroughly realized this world is.

The work is extensive and detailed. Tolkien sweated language, writing out pronunciations and such features as the use of dipthongs. This won’t surprise long-time fans, but the evidence will delight a certain kind of reader. It wasn’t until years after my initial reading, when I was studying Anglo Saxon, that I recognized the roots of the rolling rhythms, the split-line rhyme schemes of the Rohirrim (and, yes, the alliteration), evocative of a largely pre-literate society that remembers through recital.

Great attention is paid to his mythology – the basis for these books and his lifelong project, much of which was published posthumously as The Silmarillion. Yes, it is derivative, with Norse and Germanic myths weighing in heavily. One could argue that all mythology is derivative, built on the beliefs of cultures past. Or, if you believe Joseph Campbell or Carl Jung, on a shared human story that feeds our elemental needs. But here it is, visualized in paintings and sketched out in writings that give fascinating insights into the author’s universe, his understanding of the web of history, the life of his world beyond the covers of his books. The fate of the Entwives, for example, comes into the trilogy only as song reference and an unanswered question, a melancholy side note as one group of allies prepares for battle. Here, it is answered in a long, hand-written letter to Naomi Mitchison, who queried Tolkien while proofreading the first two books. (The letter is reproduced, in a much more easily readable form, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Humphrey Carpenter, which is available in the Morgan shop).

Such writings are the heart of this exhibition, although the paintings and maps are beautiful too. They also underscore the intimate nature of the show. For although the Morgan does have some larger pieces – Tolkien’s Oxford robe, for one – the majority are small and merit close viewing. The popularity of the exhibit can make that difficult, and fans may want to work in a weekday visit (a recent Friday afternoon was perfectly lovely) in order to fully enter Middle-Earth.

A former journalist, Clea Simon is the author of three nonfiction books and 26 mysteries. A contributor to such publications as the Boston Globe, New York Times, and San Francisco Chronicle, she lives in Somerville with her husband, Jon Garelick. She can be reached here and on @Clea_Simon.