Television Review: “Jane Fonda in Five Acts”

The more we hear Jane Fonda’s homilies about needing to be “whole” and “self-actualize” the more her personal journey sounds more like a succession of carefully calculated branding exercises.

By Matt Hanson

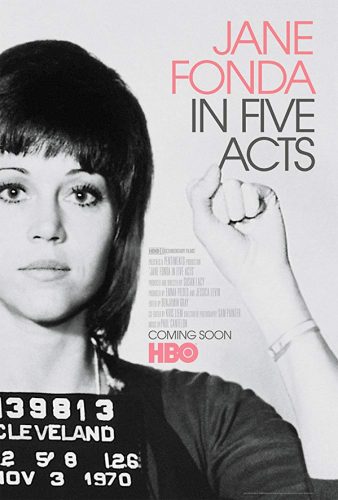

F Scott Fitzgerald famously said that there were no second acts in American life. The title of HBO’s new documentary Jane Fonda in Five Acts suggests otherwise. In some ways, Jane Fonda is an example of how pop culture, like the God of the Old Testament, giveth as capriciously as it taketh away. She went from being the intergalactic sex symbol of Barbarella to the pissed-off, rabble-rousing anti-war activist and the tough modern woman of Klute and Godard’s Tout Va Bien, to the impresario behind a series of wildly successful workout tapes, and now has attained a sort of grande dame status among the glitterati. The film gives Jane ample space to let her tell her own story, in her own words, and she narrates it with the poise and world-weary humor that comes with having survived being publicly adored and despised.

Fonda is open to the criticisms that she’s been fielding for a lifetime, and with a few exceptions she’s pretty game about addressing them. When you listen to an actor recount their life (especially one as complicated as Fonda’s) there’s always an element of performance involved. It comes with the territory. But Fonda seems credible because of her ability to be frank about her successes as well as her failures. The very well-kept septuagenarian isn’t shy about explaining how vulnerable she felt growing up in the shadow of her distinguished but utterly remote father.

Onscreen, Henry Fonda was the pensive, decent, everyman who could play Tom Joad and young Abe Lincoln and stubbornly listen to his conscience as the lone holdout in Twelve Angry Men. To his family, however, Henry was cut from the gray flannel cloth of postwar fatherhood — aloof to the point of indifference and cruelty. There’s a family picnic photo (which the film slightly over-relies on) from the forties that suggests deep alienation under the pristine surface. Daddy Fonda’s staring out into middle distance, a million miles away, and Frances the tragic mother looks at the camera with anguish. Little Jane and Peter peer at their father as if he’s a complete stranger. As the photo reappears at various points in the documentary, it begins to seem reminiscent of the bleak, enigmatic still at the end of Polanski’s Repulsion.

As Jane tells her life story, it becomes increasingly clear how Fonda had the tendency to need to define herself on her terms while constantly falling for dominating older men. After fleeing her distant father, she ran off to Nouvelle Vague Paris to fall right into the arms of Roger Vadim, whom Tom Carson memorably called “the Hugh Hefner of the avant-garde.” Vadim’s well-heeled bohemian lifestyle and cheesy aesthetics haven’t aged all that well. The film discreetly tiptoes past the sleazier aspects of their life as mere “hedonism” but it’s still a little disturbing to find out how drunk she had to be to do the famous intergalactic striptease at the beginning of Barbarella. The bulimia and anorexia she picked up at her elite private school ensured her a lithe figure. But was also the result of a deep internalization of her father’s constant nagging her about her weight.

As the war in Vietnam heated up, Fonda got woke with a vengeance. She started commiserating with antiwar activists, soaking up all the radical ethos in the air. She readily admits how messed up she was at the time and how naïve she was about using her celebrity to aid the antiwar cause. The barbiturates she got hooked on didn’t help, either. At one point, her lifelong Democrat father looked her square in the face and told her that if she ever turned Communist, he’d turn her in himself. Fonda’s impulsive photo ops with the Vietcong unintentionally provided the perfect image for right wingers to pinata the left. So much of the culture war slop that we currently wade through can be traced back to the mud thrown over “Hanoi Jane.”

The movie makes it clear that the hate she got for her outspoken opposition to the war, and the brutal ways in which it was conducted, was real. Threats to her life were constant. Fonda’s activism was fueled by authentic moral outrage, certainly, but there was definitely a raw and slightly self-righteous edge to her speechifying. Even the bemused Dick Cavett, interviewing her in the ’70s, is sympathetic — but chuckles over her headstrong, self-defeating crusading.

Once she was hitched to the radical intellectual Tom Hayden (strictly to keep the attention on her activism, and to avoid being asked about having an illegitimate child) she starts to live out her democratic principles day to day. To their credit, the family refused to have any of the luxuries unavailable to the average working-class family — that meant no washing machines, no dishwashers, driving a station wagon to the Oscars. Their son, the actor Troy Garity, humorously tells stories of being potty trained in the middle of combat zones and how there was no way for his family to pretend they were a normal bunch. But he also doesn’t question whether or not his parents walked the walk.

It is quintessentially American that, for all the radical scholarship Hayden produced, Fonda’s inspiration to make workout tapes was what made the money. Her workout tapes were runaway bestsellers, helping to create the nascent home video market. She describes how the workout helped her (and many women in her audience) to overcome her body issues. She selflessly gave up the rights; all of the proceedings went to the movement. She became the breadwinner and made quality, timely movies like 9 to 5 and The China Syndrome about women entering the workplace and the threat of nuclear annihilation, the latter released only weeks before the catastrophe at Three Mile Island. For all of her sincerely felt social conscience, it’s interesting to see how Fonda’s ability to tap into the market for female empowerment via direct marketing is what put her over the top.

It’s not all that surprising that she ended up falling for Ted Turner. Yet again, she found love in the presence of a wealthy, charismatic, outspoken liberal bad boy. Fonda clearly loved how Turner pretty much seemed to do whatever he wanted all the time. She still speaks in awestruck tones about how attractive he was. They made a perfect ’90s era power couple, mixing wealth with politics.

You can see how the lifestyle commodification trend so prevalent in the ’90s and so commonplace today became mainstream, with Fonda and Turner relishing the ability to affect global policy via the power of their celebrity. In truth, by the end of the film the more we hear Jane’s homilies about needing to be “whole” and “self-actualize” the more her personal journey sounds more like a succession of carefully calculated branding exercises.

It is a little awkward to hear Jane explain her life largely by talking about the different men in it. The story of Jane Fonda as an actress and icon has been told more fully recently, in You Must Remember This, journalist Karina Longworth’s enthralling podcast deconstructing Hollywood’s myths and legends. Fonda’s career trajectory is compared to Jean Seberg’s, another talented All-American actress who made important films, became radicalized, and ultimately couldn’t keep her head above water.

Fonda was able to stay in the game long enough to be the one to eventually take charge, which testifies to her grit and determination. Unfortunately, her gauzy talk about empowerment and wholeness cloys, a home video sales pitch by other means. But as the documentary ended, I turned to the strong, independent, accomplished woman sitting next to me and semi-ironically asked her if she thought Fonda was a good feminist role model. She considered this a minute, smiled, and confidently replied: “absolutely.”

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.