Classical CD Reviews: Prokofiev’s “Cantata on the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution” and “Music of the Americas”

It’s not Prokofiev at his finest, but his “very good” was above just about everybody else’s best. Houston Symphony’s Music of the Americas has it wooden moments.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

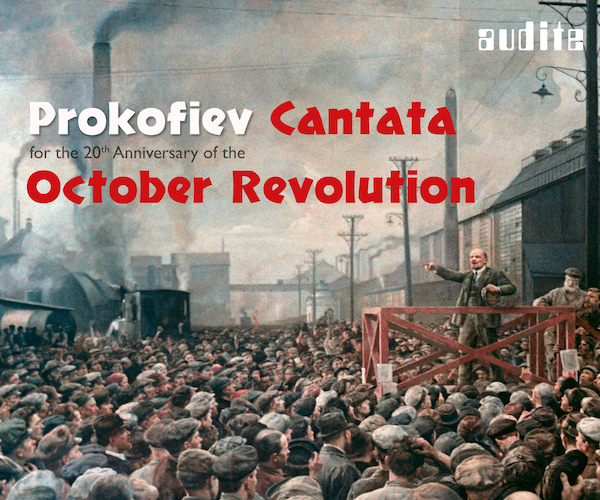

What do Stalin’s words sound like when sung? That’s a question you’ve likely not asked, at least too widely – but, for the curious, they can be found in Sergei Prokofiev’s obscure Cantata for the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution, a largely-forgotten ceremonial score that was written in 1937 but not premiered until 1966. Why the delay? Well, it seems that the powers-that-be objected to Prokofiev’s settings of Stalin, as well as Lenin, Marx, and Engels. It also didn’t help that, when the time came to audition the piece for a committee of dignitaries, Prokofiev evidently sang the choral parts himself, and badly. Perhaps it says something that he didn’t seem too hurt by the Cantata’s rejection.

With that legacy, why bother with Kirill Karabits’ new recoding of the piece on Audite? Quite simply because the performance itself is electrifying. And, if you love Prokofiev the enfant terrible, well, this is a great example of that raucous, gritty style married to the mature composer’s sense of musical theater.

And that last quality carries it far. Stylistically, the music runs a gamut from devotional, quasi-religious chants to stirring, patriotic fare (of, particularly, the mid-century Soviet kind) and spends a fair amount of time revisiting the dissonance and musical chaos of much cutting-edge Russian music of the ‘20s. Its central movement, “Revolution,” for instance, features accordion, amplified speaker, and wailing siren (among other things).

What’s more, little in the piece seems to be what it appears. The texts – settings of the Communist manifesto, plus speeches and writings of Lenin and Stalin – are juxtaposed by ambiguous (sometimes seemingly contradictory) instrumental interludes.

Was Prokofiev attempting to have it both ways with the regime, writing a cantata to glorify it while not shying away from the harder truths of life under it? We’ll probably never know for sure, though, given the music’s ambiguity, that seems to be a plausible explanation.

The current performance by the Ernst Senff Chor, Staatskapelle Weimar, and conductor Karabits fully embraces the music’s wild contrasts of extremes. The choral contributions are mighty: sometimes fierce, sometimes warm, always robust and precise. Much the same can be said for the orchestral playing, which is full of biting rhythms, aggressive attacks, and a wild array of colors. It says much about the interpretation, though, that the piece comes over with such cohesion, never, even in its loudest episodes, simply dissolving into noise. This is an ensemble and conductor that have the music in their blood and they proselytize for it accordingly.

While the disc itself hails from a concert performance, the engineering all but eliminates the audience noise and the only real evidence of live recording comes via a handful of tentative transitional orchestral episodes. But those don’t diminish the overriding impression of the album or the piece which, though short (less than forty-five minutes), is packed with invention. It’s not Prokofiev at his finest, but his “very good” was above just about everybody else’s best.

Music of the Americas, the Houston Symphony’s (HS) new survey of pieces by Silvestre Revueltas, Leonard Bernstein, Astor Piazzolla, and George Gershwin offers, true to its title, a cross-section of 20th-century music written in this hemisphere. And much of it is connected, historically and thematically, in intriguing ways. But, in terms of the performances, this is a rather grim, dreary vision of the place rather than an invigorating, uplifting one; in a way, then, perfectly appropriate to the times.

That said, there are individual things to like in the orchestra’s performance of the “Symphonic Dances” from West Side Story: the orchestra’s got a weighty but flexible sound that nicely ground parts of the “Prologue” and “Mambo”; there’s some conspicuously fine woodwind and brass playing in “Somewhere” and “I Have a Love”; and many subtle details of the scoring come across with clarity.

But at important junctures, the reading is a bit wooden. Tempos can be leaden and the level of excitement is inconsistent, movement-to-movement.

That’s too bad, because, when he’s on, Orozco-Estrada has the measure of much of this piece and those spots (“Cool,” the “Rumble,” “I Have a Love”) are great; it’s the other ones (and mostly over its first half – the “Prologue,” “Mambo,” “Cha-cha,” et al.) that are too inhibited when the music simply needs to cut loose

It’s appropriate that there’s a big Bernstein score on this disc because two of the other three pieces here were recorded quite more emphatically by the older musician.

The first of those, Revueltas’ Sensemaya, can be a wild musical ritual: it’s based on a poem about the ceremonial killing of a snake. Here, though, it’s blazing colors and driving rhythms are shaded and rather dull. It starts off well enough – the opening riffs, trills, and ostinatos are plenty mysterious – but when the music really needs to drive forwards over its last third it holds back. The result is anticlimactic.

The other, Gershwin’s An American in Paris, is nicely shaped, structurally. And there’s some strong playing from the HS to boot, especially Mark Hughes’ idiomatic trumpet solos. But the whole reading is too often soupy and sluggish. The opening section is as stiff, earthbound, and joyless as I’ve heard, and the bluesy middle part simply drags. Worst of all, the climactic Charleston is anything but peppy: it’s rigid and four-square. James Levine’s much-criticized reading of this piece with the Chicago Symphony is, by contrast, played with authentic Jazz Age sensibility.

Where things seem to come together best is in Piazzolla’s Tangazo. A 1970 score that expands the traditional tango in both duration and orchestration, its sultry, slow sections move with purpose while, in the pulsing, rhythmic passages, the orchestra finds a measure of rhythmic and expressive freedom that’s lacking in the disc’s other scores. Go figure – but, given the ready availability of superior recordings of the surrounding pieces, it turns out that Music of the Americas’ one rarity comes off particularly well. If only the rest of the album had, too.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.