Book Review: “Birdcage Walk” — Helen Dunmore’s Exhilarating Farewell

Helen Dunmore’s astounding final novel is a fascinating take on a family of radicals living in Bristol, England during the French Revolution.

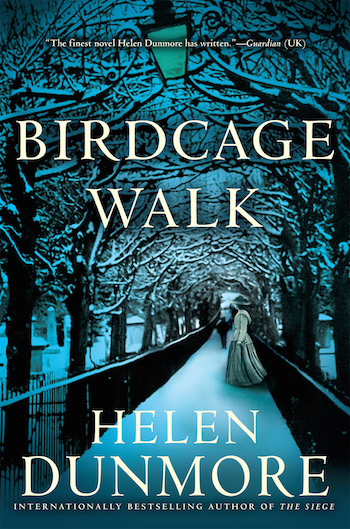

Birdcage Walk by Helen Dunmore. Atlantic Monthly Press, 407 pages, $26.

By Roberta Silman

Helen Dunmore was a marvelous, fearless English writer who died far too young of cancer this past June at the age of 64. She was the author of fifteen novels as well as several books of poetry and children’s books. Her energy and imagination seemed boundless, and her willingness to take risks in her fiction — writing about so many different times and places and people — made her unique in a time when so many of her contemporaries seem to be writing the same book over and over again. As a winner of the inaugural Orange Prize (the best fiction by a woman), as well as many other honors, she was well-known in her native England, and deserves to be much better known here.

I loved her penultimate novel Exposure when I reviewed it at the end of April in 2016, and although I thought her earlier novel The Greatcoat (reviewed in Arts Fuse in 2012) a bit contrived, I am only now beginning to go back to her earlier work and learning how enormous her talent was. I can recommend with the highest marks her two novels about Russia after the war — Betrayal and The Siege — as well as this astounding last novel, Birdcage Walk, a fascinating take on a family of radicals living in Bristol, England during the French Revolution.

Perhaps her fearlessness came from her intimate knowledge of fear. Like no other 21st Century writer that I know, she seems to know and convey fear in an intense and uncanny way, making what is actually outstanding literary fiction walk the fine edge towards thriller, and thus creating her very own genre. You rarely feel manipulated by Dunmore as she takes you back in history; instead you feel exhilarated, as she spins her own take on events you thought you knew and/or had read about too often before.

In a moving Afterword to Birdcage Walk (which is really her goodbye to her readers) she talks about what propelled her to write so much and so deeply about so many periods of history. She comments, “I am writing . . . about the ways in which the individual vanishes from historical record.” A little later she posits,

Only a very few people leave traces in history, or even bequeath family documents to their descendants. Most have no money to memorialize themselves, and lack even a gravestone to mark their existence. Women’s lives, in particular, remain largely unrecorded. But even so, did they not shape the future? Through their existences, through their words and acts, their gestures, jokes, caresses, strength and courage — and through the harms they did as well — they changed the lives around them and formed the lives of their descendants.

Here Dunmore could be describing her fictional character, Julia Fawkes, whom she makes clear in her Prelude to Birdcage Walk was a writer living at the end of the 18th century in Bristol. Her work was never published, but her energy and intelligence shape the characters who outlive her: her daughter, Lizzie, Lizzie’s husband John Diner Tredevant, her son Thomas, Lizzie’s stepfather Augustus and the servants, Hannah and Philo who are so loyal to this family through both obstacles and joys. Hovering over the novel is news from France where the French Revolution is unfolding, but central to it are more intimate questions of what happened to John’s first wife, Lucie, who was a French milliner, and what will happen to Lizzie as she tries to fill the role of John’s second wife. She has married him against her beloved mother’s wishes, and attachment and loyalty to Julia is pitted against her love for her new husband throughout the first half of the book.

After the Prelude, we see John burying Lucie in an unmarked grave located in a forest glade only he seems to know about. How she died and why remain a mystery until the end of the book, but because of that harrowing first chapter, we, the readers, and Lizzie are haunted by Lucie, by Lizzie’s hallucinations about Lucie, by John’s volatility, which seems directly traceable to Lucie and, finally, by a growing fear for Lizzie that becomes almost excruciating. John Tredevant’s values could not be farther from those of the liberal Fawkes family: he is a rough man, a builder by trade who is embarked on a scheme to construct terraced housing over the famous Bristol Gorge. He cares nothing for Lizzie’s ideals or feelings; he reminds her she is chattel, and grows increasingly paranoid about his business and his wife.

As Lizzie shuttles between her maternal home and her married home, we become privy to how these English liberals reacted to events in France that were becoming steadily more violent and horrible. We see Julia’s active mind at work, we feel her engagement with political events, her role as an intellectual. We also witness her need to help Lizzie mature and become more worldly. When she becomes pregnant at the age of forty, Lizzie is the last to realize what is happening. Here they are after Lizzie learns the truth; she is trying to comfort her mother about the future and has offered to help with the new baby:

‘Of course you will not, my darling.’

She was right. I had offered because I knew nothing of what a baby meant. Hannah and Mammie had cherished me but they had also made me strong. They did not let me understand that I had any limitation. They had brought me up to believe that in mind and spirit I was the equal of any creature on earth. I could read and cook and sew and pack our belongings into boxes for the carter to take us from lodging to lodging, and I could walk as far and fast as any boy.

‘Why should it hinder your work, Mammie? Between Hannah and you and me, there are three pairs of hands. Surely no baby can require more than one at a time. Or you can put it to a wet-nurse,’ I added, although I knew she did not believe in wet-nurses.

‘Don’t think about it any more, Lizzie. I’ll keep on writing, Augustus will continue to travel the length and breadth of Britain, and . . .

And nothing, she implies, will change. But having at baby at the end of the 18th century is extremely dangerous. And after Julia delivers Thomas, everything changes.

In one vivid scene after another Dunmore gives us a detailed portrait of life in southern England at that time: the poor living conditions, the dirt and vermin, the terrible hazards of blood-soaked childbirth, the subjugation of women, the place of servants, the scrabbling for money, the ridiculousness of some of the privileged like Caroline Farquar, the way large Micawber-like dreams can ruin a man who is counting on world events to propel him to prosperity. Indeed, at times it feels as if you are reading some modern version of Dickens or Trollope and, for me, that only heightens the pleasure.

The late Helen Dunmore — she seems to know and convey fear in an intense and uncanny way. Photo: Wiki.

Yet Dunmore’s voice is all her own. And although she never slips from the period she has laid out for herself, her characters have a thoroughly modern feel. Julia hovers over the book as only a beloved and exacting mother can. Lizzie can be lovable and sometimes smart, but she is also exasperating in her innocence. Augustus is well-meaning but finally becomes foolish in his ineffectiveness. Dunmore is also very good, as she was in Exposure, on the power of sex; there are times when John and Lizzie reminded me of Heathcliff and Cathy in their inchoate but very real passion for each other. It is a passion that seems always to have a component of fear, a fear that gives rise to all kinds of suspicions and jettisons any idea of equality between a man and woman. Indeed, although we don’t know this until the end, we have also been reading about what violence can do to people, how it can warp their lives and kill any hope for a future. Or make them stronger, more courageous, so that they can finally extricate themselves from the gnarled tangle that brutality, by its very nature, creates.

We read fiction so that it can change our angle of vision. Make us see the world more richly, help us to understand the puzzles we are facing in our lives both personally and politically. This is a book entirely relevant to events we have been living through, and I think Dunmore felt that keenly as she wrote Birdcage Walk. Here she is, at the end of that heart-breaking Afterword written just about a year ago:

While I finished and edited [this last novel] I was already seriously ill, but not yet aware of this. I suppose that a writer’s creative self must have access to knowledge of which the conscious mind and the emotions are still ignorant, and that a novel written at such a time, under such a growing shadow, cannot help being full of a sharper light, rather as a landscape becomes brilliantly distinct in the last sunlight before a storm. I have rarely felt the existence of characters more clearly, or understood them more deeply — or enjoyed writing about them more.

What a poignant farewell from a writer who deserves to be known and read and re-read and cherished. Take her to your book clubs and reading groups, give yourself over to those people she brings alive so wonderfully, and thank God for the prodigious energy and persistence she had while she was alive. Her work is a gift to us all and will surely be read through the ages.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.