Book Review: “The Feud” — Brilliant Literary Frenemies

Alex Beam generates interest via his portrait of frenemies Edmund Wilson and Vladimir Nabokov as brainy but flawed human beings.

The Feud: Vladimir Nabokov, Edmund Wilson, and the End of a Beautiful Friendship by Alex Beam. Penguin/Random House, 224 pages, $26.95.

By Matt Hanson

When Vladimir Nabokov arrived in New York in 1940, fresh from Nazi occupied Paris with his wife Vera and their young son, he had virtually nothing to declare but his genius. Fleeing their home after the Russian revolution and haunted by the tragic death of Nabokov’s liberal and affluent father, who took a Bolshevik bullet intended for a friend, the family lived in penniless European exile for over a decade. In the Russian expat community Nabokov became a literary star, his high standing established via several superb novels (including The Gift) and stories written under the pen name Sirin. But Nabokov was virtually unknown in America, and when he came to this country he desperately needed a muscular highbrow publicist.

Luckily, his cousin happened to be a Cape Cod neighbor of Edmund Wilson, one of America’s leading literary critics. Wilson was a public intellectual and a scribbler of all trades: drinking buddy and sounding board for the Lost Generation, literary tastemaker for influential magazines like The New Yorker and The New Republic, and a legendarily erudite and fiercely left wing critic, novelist, and historian.

Wilson was fascinated by Russian culture and language and agreed to meet this interesting émigré for drinks. The two got along famously, almost too well: eventually, their diverging ambitions and mutually insufferable pedantry broke their deep friendship apart, creating the most notorious public literary dispute of their time.

Alex Beam’s brisk, witty, and well researched The Feud tells the surprisingly entertaining story of how these two literary giants fell in and out of love with each other. Beam takes us up close and personal, and makes the reader an amused witness to the kind of literary dustup that is no longer in vogue in our conformity-ridden, conflict free, and network-till-you-drop literary landscape.

Initially, Wilson was very good for Nabokov’s career, generously offering a blurb for his superb novel The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and making arrangements for the writer to review books and apply for desperately needed academic posts. The two bookish lions argued about everything under the sun, but it was the kind of intellectually stimulating contest that both parties found valuable. In some ways, Nabokov and Wilson were each other’s ideal reader, savoring one another’s learned allusions and admiring a fine turn of phrase or apt metaphor, often written in one of the several languages they shared.

Their literary reciprocity wasn’t only limited to highbrow matters, either. They called each other by their lifelong nicknames “Bunny” and “Volodya” and their families spent many festive dinners together. Vera, Nabokov’s devoted wife and to whom everything he wrote was dedicated, rolled her eyes when the two of them spent an evening reading aloud from a contraband copy of the erotic French novel The Story of O, “snickering like schoolboys.” Nabokov said in a letter to Wilson that he was “one of the few people in the world whom I keenly miss when I do not see them.”

Their high-spirited conversation was not to last; aesthetic and political fissures began to crack open and widen over time. Wilson was an accomplished linguist with a decent grasp of Russian (a notoriously tricky language to master), but he vainly overestimated his ability to read or translate from it accurately, causing the Nabokovs to chuckle over Wilson’s pretentions in private.

Wilson was also more stridently leftist than Nabokov could stomach. After seeing the devastation of the Great Depression up close as a young man, Wilson spent much of his journalistic career eloquently denouncing the ravages of capitalism. Like many leftist intellectuals of his time, Wilson felt passionately about the egalitarian potential of the Soviet Union, spending years writing the epic, vivid, but flawed To the Finland Station, a vibrant history of socialism culminating in the Bolshevik revolution.

Having had more than his fill of Bolshevism, Nabokov wearily countered that Lenin was “a pail of milk of human kindness with a dead rat at the bottom.” Nabokov hated any argument that favored politicizing literature, and proudly claimed (somewhat disingenuously) that his books were utterly devoid of social purpose. Wilson’s valorizing of Lenin and Trotsky as men of thought and action was pushing it too far. To his credit, Wilson eventually admitted that he had relied too heavily on party-approved texts and made sure to emphasize the hideousness of Stalinism in later editions of To the Finland Station.

Nabokov enjoyed Wilson’s 1946 story collection Memoirs of Hecate County, a portrait of dissolute suburban life, but felt that some of the book’s then-controversial descriptions of sex were less than sexy. He explained to Wilson that “the reader derives no kick from the hero’s love-making. I should have as soon tried to open a sardine can with my penis. The result is remarkably chaste, despite the frankness.” American censors disagreed; the book was banned in several cities. The case filed to challenge the censorship ended with a Supreme Court deadlock (Felix Frankfurter, a friend of Wilson’s, recused himself — an outraged Wilson never forgave him).

The scandal boosted sales for a while, but Hecate County eventually faded into obscurity, to Wilson’s great disappointment. But it did have an unexpected impact on literary history: when Nabokov’s far more brilliant and outrageous Lolita was published in 1958, the public’s tolerance for risky literature had eased up. Wilson was no puritan, but he was oddly baffled by Lolita, never finishing it. He may have been more jealous than he wanted to admit when his friend’s novel became an enormous success. Widely considered a masterpiece, Lolita made its author a very rich, respected, and famous man.

All of these factors may have come to a head when Wilson decided to publicly lambaste, in the pages of the New York Review of Books, Nabokov’s English translation of Alexander Pushkin’s classic verse novel Eugene Onegin. Wilson and Nabokov both revered Pushkin, but each of them brought nagging concerns to the value of the new translation, which was published in 1964. Wilson was right to criticize Nabokov’s eccentric use of English grammar and vocabulary choices (what the hell are “sapajous” and what does “stuss” mean?) as well as the “tedious and interminable appendix,” which ran to almost a thousand pages of hilariously pedantic, arcane specifics about Russian objects, customs, and etymology.

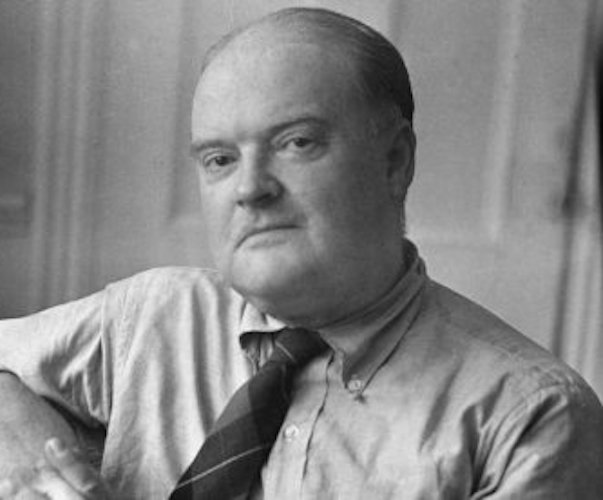

Critic Edmund Wilson — A refined mind that argued over proper gerund use.

Plenty of experienced Russian translators were befuddled by the book’s winding labyrinth of prose and verse. Nabokov may have even understood that he had gone to far, at least on an intuitive level. His novel Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (published in 1969) has a satirical flavor; it is jam-packed with dizzying, discombobulated references, parodies, and obscure allusions — to the point of being unreadable. But Nabokov wasn’t content to let Wilson have the last word on how he translated his mother tongue in English and was angry that the critic had dared to lecture him on the proper way to read the towering masterpiece of Russian poetry. Even after their decades-long correspondence stopped, the argument over Eugene Onegin continued, a series of other writers and academics taking up the endless squabble.

Beam’s genial prose takes us through the complicated and occasionally absurd scuffles that lasted, in various forms, for years. He is good-naturedly aware that some of the more academic debates generated by the Wilson/Nabokov debate might be too highfalutin for the non-academic reader. He keeps his tone light and engaging and is happy to point out the silliness of refined minds vehemently arguing over the proper use of a gerund to describe a horse sniffing at a pile of snow.

What keeps this narrative of dueling geniuses interesting, aside from the thoroughly and accessibly described bouts of academic hemming and hawing, is Beam’s appreciation of Wilson and Nabokov as brilliant but flawed human beings. It’s tempting to stick one’s artistic heroes on a pedestal; this worship reflex only makes revelations of their ordinariness more compelling and rich. For as long as it lasted, the Nabokov/Wilson friendship was a match made in literary heaven; a look at the all-too-human qualities that brought it back down to earth turns out to make for a refreshingly worthwhile yarn.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Thanks for the ringside seats to this title bout between literary heavyweights.