Music Preview: Interview with Composer Adam Schoenberg

Adam Schoenberg is also one of the most widely-performed living composers of orchestral music; in fact, he’s among the top-ten in that category.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

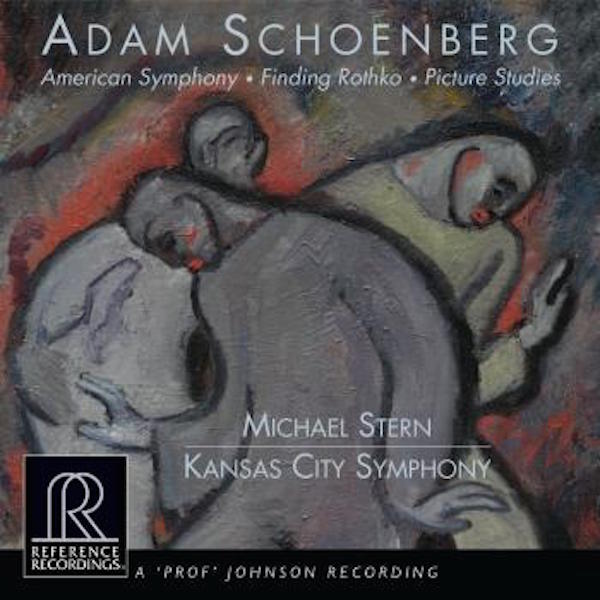

One of the first big contemporary classical music releases of 2017 belongs to the Oberlin- and Juilliard-trained composer Adam Schoenberg, who also happens to be a Massachusetts native (Northampton-born and New Salem-raised). Now settled in California, where he teaches at Occidental College, Schoenberg’s also one of the most widely-performed living composers of orchestral music: he’s among the top-ten in that category (which puts him in the heady company of John Adams and Philip Glass), and his new album on Reference Recordings features three of the pieces that helped earn him that position – Finding Rothko, Picture Studies, and American Symphony.

I recently spoke with Schoenberg and our conversation touched on a wide range of subject, from his early musical models to the new album to the intersection of music and politics and a fortuitous enthusiasm for tennis. An edited transcript of our conversation follows below.

Arts Fuse: First of all, congratulations on the new album! About the three pieces on the disc: they cover some pretty wide stylistic ground even though they’re all kind of rooted in the same sort of tonal, American symphonic tradition. Could you talk a little bit about how you developed your compositional philosophy and found yourself working within this well-worn tradition?

Adam Schoenberg: Sure. Well, you know, I’m a teacher, I love teaching and really, for me, I’m a believer in writing the music that you, first and foremost, believe in and want to hear. I’ve always been drawn to a more tonal landscape, definitely have always loved the music of Copland, loved Bernstein’s music. So, naturally, I think I fall sort of in that lineage of more traditionally American symphonic composers, though I don’t think my music is really like theirs. It’s very American, but it’s very 21st-century.

You know, as a student, we studied everyone. Dutilleux’s one of my favorite composers, even though you don’t really hear much Dutilleux in my music at all. Metaboles has been a piece I’ve lived with for a very long time and I’ve studied it inside and out, and I very much appreciate the meticulous craft and choices that go into that type of work. So a lot of orchestration colors, I think, come from French composers like Dutilleux and Marc-Andre Dalbavie. But, you know, I’m also into Radiohead and you hear a little Radiohead in there, and Pat Metheny – whose music is so different from them – all these different influences get woven together in my landscape.

AF: Two of the pieces on the disc – Finding Rothko and Picture Studies – have picturesque titles and direct connections to visual art. When you were writing those scores, did you find that your approach differed with how you wrote your more abstract works (like American Symphony)?

Schoenberg: Well, those were very specific commissions, especially Picture Studies. With that piece, the Kansas City Symphony basically said, “We want to commission a 21st-century Pictures at an Exhibition and it needs to be inspired by works of art from the Nelson Atkins Museum” (which also co-commissioned the piece), so there’s a greater sense of responsibility from that work to absolutely have at least each opening gesture of each movement be symbolic of the artwork that I was setting.

I didn’t score Picture Studies like a film score, but [each painting] absolutely provided immediate inspiration. I would take very detailed descriptive notes about what I was experiencing while viewing each image, and that led to some type of descriptive narrative in terms of style, musical language, energy, tone, color – so in many ways it was almost like my muse, where I would write down adjectives and words and, in some cases, map out some formal ideas. So, I was sort of vaguely setting them.

That said, overall the pieces stand on their own, without needing the image to understand what’s going on.

Whereas in American Symphony that had a much more intellectual and emotional narrative.

AF: In your notes for the Symphony you mention the model of Copland’s Third Symphony being kind of the summit of the American symphonic repertory. What challenges did that awareness bring to writing this piece?

Schoenberg: Well, it’s a two-fold answer because, first of all, what does it mean to even be writing a symphony in 21st-century America? In some ways it just seems like an unnecessary term.

You know, the 2008 election was such an important election for me and for many others of our generation that I felt empowered to do something. We all have civic responsibilities and I never felt a part of that responsibility prior to that election. Suddenly, I was a young adult and I felt that I had to contribute and to do something to make our country and our world hopefully more beautiful somehow. How could I do that? Well, I thought about writing my first symphony.

The name American Symphony just came to me. At the time, it felt to me like it wasn’t probably a good idea to use it, but it never really left me. I worried that it could carry some some negative connotations or unwanted baggage for some people – who knows? But the Copland, you know, that was written at a time of such difficult world turmoil. And in 2008 our country was sort of a hot mess in so many areas. So there was that type of connection.

AF: Looking back, in 2008 the goal was to celebrate this great moment in American history and to create a joyous, beautiful response. Today, the mood is rather different. How, then, 1) do you respond, as a composer, to the changed climate and 2) how do you experience the American Symphony in the context of today’s political scene?

Composer Adam Schoenberg. Photo: Adam Schoenberg.com.

Schoenberg: What’s really interesting is that I just put the double bar on my Second Symphony [for band]. And I was thinking, “God, I was inspired to write my first symphony three days after President Obama was elected. And now I’m writing my second symphony!” I began my Second Symphony over the summer. I’m a dad and I’ve got two young boys and I love being a dad, and I wanted to write a symphony for children: you know, dreamy and uplifting. And, suddenly, this election happened and I threw out half the piece. I realized I needed to do something different: I realized I just couldn’t write this piece anymore.

And, for a time, I was actually really nervous about this CD is coming out on Inauguration Day, because I really don’t want to talk about the album then. But I realized that I wrote the American Symphony with this sense of hope and optimism, and here we are eight years later and now more than ever we need to be reminded of those things. So maybe it’s a blessing that the CD was delayed for so long [the performances were taped in 2014]. And there’s almost something serendipitous about it coming out on Inauguration Day.

And, yes, Trump won the election: he won the electoral vote; he certainly did not win the popular vote. Our country is extraordinarily divided. And this piece is really extremely – well, not the whole composition – but there are very uplifting and hopeful, optimistic moments in it. Maybe it does enter into the world at the right time.

AF: The next symphony premieres in March?

Schoenberg: Yes, it premieres March 5th at the University of Texas-Austin and then they take it on tour and it ends at the National Band Convention. And they’re recording it, as well.

It’s called “Migration” and it’s about immigration. My wife was born in Panama and grew up in Peru. So our boys, on my side, are fifth-generation American. But on my wife’s side, they’re first-generation Americans. They’re the first people in her family born in this country.

She’s Latina and I’m a white, Jewish guy. What does that mean in the 21st century? In our country, in particular, white people are going to be the minority sooner or later – it’s inevitable. But we have this person who wants to build a wall, who wants to deport people, and all. So what about all the people who have immigrated here? That’s what I try to address in the new symphony: suffice it to say, it’s a much darker piece.

AF: Of course. And one hopes that it will speak to the moment and gain similar traction as the American Symphony. Briefly getting back to that work, how did it happen that it became so widely played and championed?

Adam Schoenberg at the world premiere of the American Symphony. Photo: Adam Schoenberg.com

Schoenberg: I really don’t know! This is the thing: all of my music gets performed a lot, which is unusual for new music. You know, Finding Rothko has been performed over fifty times now. It’s usually one of the most-performed works of the 21st century, certainly of our generation of composers. And I don’t know why that’s happened but I think that, for whatever reason, orchestras and audiences have been drawn to that piece. And it’s the same response with American Symphony. All of my orchestral commissions – every piece that’s been commissioned – has been played by at least two different orchestras, meaning it’s gone beyond the premiere. So I don’t know. I feel very fortunate.

With American Symphony, that’s a little harder to explain. Finding Rothko’s just about sixteen minutes and it’s been performed so much now that I literally have this list of notes that, when conductors contact me before the first rehearsal, I just break the piece down and it can be rehearsed very easily in forty-five minutes.

Whereas American Symphony requires at the bare minimum two hours of rehearsal time. It’s just a more difficult piece. And Picture Studies is even harder: it needs a solid two-and-a-half-to-three hours. And that, you know, is a tough sell. The typical concert format is an opener under ten minutes, a concerto, and a big symphony. They’re going to spend the most amount of their rehearsal time on the big symphony, the piece everyone knows.

But that format is starting to change. Audiences and orchestras are realizing that it might not be a bad idea to program a new piece on every program because there’s a lot of good stuff out there. And audiences want to hear it.

AF: That’s right – and substantial new pieces, like your Symphony. One last question: you’ve developed a strong relationship with the Kansas City Symphony Orchestra and conductor Michael Stern, who are featured on this new disc. How did that come about and have you got any new projects in the pipeline for/with them?

Schoenberg: So, I was a student at Aspen for a couple of summers and then I actually also became a stagehand and started working there. I think I was there four or five summers, first as a student and then as a stagehand. In many ways, it was one of the greatest experiences for me, to work backstage and learn how an organization operates and just all the necessary people who are involved to put on a production. As a stagehand, I was always setting up stands, chairs, making sure performers were happy, and I met Michael Stern there, who was conducting.

And, you know, one thing led to another. I’m a pretty avid tennis player and word got around eventually that I was a good tennis player and he actually approached me backstage one day and said, “Hey, I’m looking to hit with someone” and I said, “Sure, let’s play!” So we started playing for the rest of the summer. And I never really told him much about me and, at the end of the summer, he asked where I was going in the fall and I said, “I’m going to Juilliard for my Master’s.” And he said, “Oh, let me see some of your music.” So I sent him some music and, six months later, I got an email saying he was programming something and then he commissioned me. And that piece was Finding Rothko.

Michael’s connected to all three pieces on the disc, actually, and Kansas City’s specifically commissioned the two bigger works [American Symphony and Picture Studies]. And, yes, we will do something again, but, at this point, it’s not been determined what, exactly, that’ll be.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Adam Schoenberg, American Symphony, Finding Rothko, Picture Studies