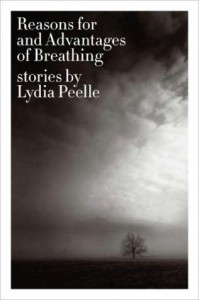

Fuse Interview: Boston native Lydia Peelle wins 2010 Whiting Writers’ Award

The Whiting Award winner’s short story collection is made up of tales filled with a gentle lyricism as well as a clear-eyed concern for characters stuck in “survival mode,” men and women, sheep farmers and taxidermists, who are scraping by, past their prime, or morally lost.

By Bill Marx.

Born in Boston and raised in North Andover, Lydia Peelle is one of 10 writers receiving the 2010 Whiting Writers’ Award, a prize aimed at encouraging fledgling writers of distinctive promise. The $50,000 award has been given annually since 1985 and boasts an impressive list of past recipients including Michael Cunningham, Kim Edwards, Tobias Wolff, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Mary Karr.

The Whiting judges were impressed by Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing, Peelle’s 2009 short story collection, pointing to “her beautiful prose, gorgeous sentences, flawless ear.” “These are very dark stories; her vision is severe, ” they observe, “while she never confronts it didactically, her sorrow about what we are doing to ourselves and to our planet is overwhelming.” Peelle received an MFA from the University of Virginia; she now lives in Nashville, where she is working on a novel.

Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing is made up of tales filled with a gentle lyricism as well as a clear-eyed but sympathetic concern for characters stuck in “survival mode,” men and women, sheep farmers and taxidermists, who are just scraping by, past their prime, or morally lost. Via email, I asked Lydia Peelle some questions about the collection, beginning with what influence, if any, New England has on her stories, which are generally set in the South.

Arts Fuse: Although the stories in Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing are not set in New England, are there any ways in which your years in Boston influenced your writing?

Lydia Peelle: Yes, definitely. I have always thought that growing up in Massachusetts made me more attuned to subtle detail in the landscape. Being a kid in Henry Thoreau’s world, not John Muir’s —no soaring mountains or redwoods, but instead low hills scraped by glaciers and beautiful, tiny pitcher plants and maple trees in the woods behind my house. I spent a lot of time outside growing up, and I think that learning to look closely for beauty in the land—and finding subtle beauty all around—has very much influenced my writing. (And when I say beauty, I mean terrible beauty, too.)

AF: Many of your characters are cut off from nature—yet animals (goats, dogs, mules, a possibility apocryphal panther) are strong presences in most of the stories. Is it that we can’t live with or without nature?

LP: We can’t live—literally—without it, and we’re doing an enormously awful job of living with it.

I am very interested in human relationships with animals—both domestic and wild—because therein is such an immediate link to the natural world. In the case of domestic animals, the gifts that our relationship with animals can give us are immense, if we can pay attention and stay present and attuned. I don’t mean by treating them like children or spending loads of money on things like herbal supplements and special dog ice cream for them—though I know we do this out of love, I think it’s gotten out of hand. They aren’t children, and we need to remember that—though I know, from experience with my own two dogs, it’s hard sometimes.

When we actually try to understand our relationship with our pets—in which we manage to communicate on a daily basis with a being that innately knows an entirely different language than our own—it is amazing that we have somehow, over thousands of years, made it work—and even more so, that they have made it work. In turn, thinking about this, for me, reflects quite a good deal about our relationships with each other—with other human beings.

This is all a window—and a door—into our fragmented relationship with the larger world we live in, a world we have so long considered ourselves separate from that we make the distinction of calling it “the natural world.” I’ve never liked that term because the last thing we should be doing is thinking of it as a separate thing. It is the air we breath and the food we eat and all the things that makes being human and alive a worthwhile venture.

AF: The Whiting selectors note that “While she never confronts it didactically, her sorrow about what we are doing to ourselves and to our planet is overwhelming.” Do you see your stories as warnings? The collection suggests that important elements of America’s promise are slipping away.

LP: Well, a lot of what we now understand as “America’s promise” stands in direct opposition to what I’m talking about above. The idea that success is measured in what you can buy. I heard somewhere a while ago about the importance of making a distinction between “standard of living” and “quality of life.” While the former may be rising for a small segment of the population, the latter is falling, in my opinion, for all of us—rich and poor alike.

AF: One critic, commenting on the collection, states that love “is the dark matter in these stories, visible mostly in some negative form.” Do you agree? You focus on characters who seem to be in permanent “survival mode,” living on the margins of society. They don’t seem to have much time or capacity for conventional bonds.

LP: I am interested in how love makes us do stupid and awful things. The stupidest and most awful.

AF: In some of the stories in the collection, such as “Phantom Pain” and “Shadow on a Weary Land,” I sense a sharp satirist held in check—could you talk about your use of humor?

LP: Well, I don’t know. A lot of times I think things are really funny and no one else does. Certain words and phrases are really funny to me. A funny thing I’ve seen lately is an entry I found in an old dictionary: under the definition of the word “Gothic,” there is a line that reads “This line is in Gothic type.” In Gothic type. That a sentence can be about nothing other than its own self is amusing to me in a geeky, English major sort of way. That’s a long way of saying there are times in my stories I put in words or phrases I think are funny, sort of as an inside joke, if nothing else to amuse myself during the writing process. “OBO”—the classified ad acronym for “Or Best Offer”—is an example of that in “Shadow on a Weary Land.” I laugh just thinking about “OBO.” I should probably get out more.

AF: Do you see your work fitting into a tradition of Southern writing? And does it irritate you to have your writing continually called elegiac?

LP: I don’t know if I can say anything about the Southern tradition. My work is about the South because it’s where I happen to find myself, and writing about it has been a way to get some sort of a bearing here.

It’s funny you should ask about the “elegiac” label. I have been thinking about that. If my work is an elegy, it’s an elegy for a time so long ago I can’t even contemplate it. I’m certainly not nostalgic for the America of 1910 or 1840 or 1950—I don’t have rose colored glasses for the time periods I write about. That said, I think if you aren’t immensely saddened by the direction we are headed in the world right now—gathering speed with every year—especially in our relentless, near-contemptuous treatment of the land and the oceans and of all the creatures we share it with, without which we have nothing—then you aren’t paying attention.

All that said, behind that sadness, in spite of and in the midst of that sadness, there is still so much joy, and I love that fiction can remind us of that. In what I’m working on now, I’m thinking a lot more about the joy.