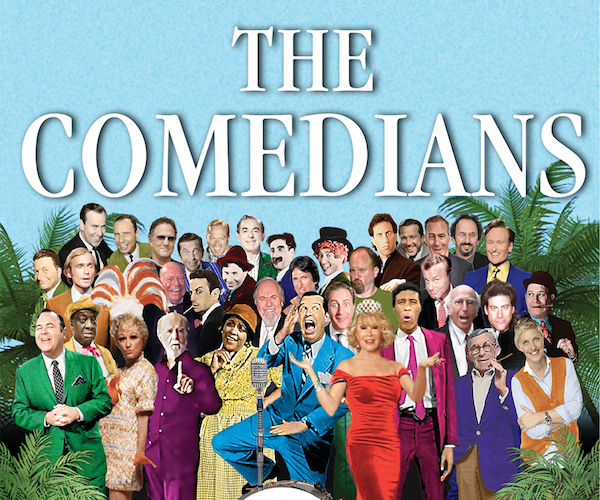

Book Review: “The Comedians” — A Compelling History of America’s Jesters

I loved this book. It is juicy, often funny, and sometimes dark and disturbing. It will hold a cherished place on my comedy book-shelf.

The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, no k Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy by Kliph Nesteroff. Grove Press, 432 pages, $28.

By Betsy Sherman

Kliph Nesteroff’s The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy is a durn-near comprehensive (I’ll get to my quibbles later) history spanning over 100 years of American comedy. Not American humor—American comedy, meaning the genre’s who, when, where and especially how, rather than the what of performers’ subject matter. This phenomenal achievement is authoritative without sounding academic. It’s juicy, often funny, sometimes dark and disturbing. It’s sure to send you straight to YouTube to check out the comics you’d never heard of and binge on old favorites.

I count myself as a major comedy nerd, launched on that path by the old afternoon talk shows of Mike Douglas and Merv Griffin. The parade of funny people who cycled through these showbiz-fests included such forgotten stand-ups as Totie Fields, Jackie Vernon, Pete Barbutti, Charlie Callas, and the nebbish-y Stanley Myron Handelman. Today, I’m addicted to podcasts in which comedians interview other comedians. Yet I was consistently surprised at the nuggets turned up by Nesteroff (who, in spite of his wealth of knowledge isn’t an old Borscht Belt yoda, but a native of Canada only in his 30s). Here are just a few things I learned:

• When Milton Berle was a kid, his mother thought neighbor Phil Silvers would be good influence on him. Young Phil took his new pal to a whorehouse to lose his virginity.

• Hal Roach, the comedy mogul who oversaw the work of Laurel and Hardy and Our Gang, in 1937 formed a production company with Benito Mussolini’s son Vittorio.

• One of the most popular comics playing before audiences in Broadway’s thousand-plus seat presentation houses during the 1940s was an elegantly dressed female “joke machine” named Jean Carroll.

• Woody Allen is an alumnus of the short-lived NBC Writers Development Program.

• Colorful stand-up Buddy Hackett talked out of one side of his mouth because while helping his upholsterer father he’d hold the nails in his teeth on that side.

• The questionable practice of sweetening TV sitcoms with canned laughter almost carried over to the movies. Some prints of Cat Ballou were sent out with a laugh track.

• Redd Foxx and the African-American record executive Dootsie Williams in the mid-1950s launched the trend of stand-up comedy albums, a genre which by the 1960s competed in the charts with music records.

• Louis C.K. counts The Unknown Comic—a jokester on TV’s Gong Show who wore a paper bag over his head—as a major influence on his decision to go into comedy.

The Comedians covers comedy in various broadcast and recorded media (although it doesn’t dwell much on movies), but chiefly concentrates on that archetype of the lone person with a microphone facing a live audience. The magic of the moment is supreme. The author conducted more than 200 interviews for the book, most importantly with elders such as the never-shy stand-up Jack Carter, who provides many of the book’s exclamation points (he died this year at 93).

It begins with a short profile of Benjamin Franklin Keith (the “K” in RKO), a mogul who created the largest vaudeville circuit in America and who first made big bucks by pulling in suckers to ogle a collection of preserved prematurely born babies (it was known as an “incubator show”). The book ends with the suicide of Robin Williams. What this progression illustrates is that although the people who provide the means to entertain are important—and Nesteroff shows the whole constellation of venue owners, agents, managers and executives who could facilitate or impede a performer’s connection with the audience—it’s the sensitivity and courage of often-fragile artists that turned joke-telling into a mature art form.

The opening chapter about vaudeville contains names that may be familiar to all (the Marx Brothers), some (Eddie Cantor), and practically nobody. Among the last is Frank Fay, whose sharp patter as a master of ceremonies earned him a place in history as the original stand-up comedian, but who became notorious as the alcoholic husband of rising star Barbara Stanwyck (their marriage inspired A Star Is Born). The next segment is radio comedy, which killed off vaudeville as surely as television eventually killed it. Jack Benny, the team of George Burns and Gracie Allen, and Milton Berle were able to move successfully from platform to platform; the brilliant Fred Allen foundered after radio success.

The exciting and precarious world of post-Prohibition nightclubs follows. Says one old-timer, “If you were a stand-up comic, you worked for the Mob,” or, as it was politely called, The Outfit. For a while, Miami Beach was as thriving a center of lounge-based hilarity as New York or Chicago. Boisterous, booze-fueled insult comedy erupted, with a guy named Jack White paving the way for Don Rickles (and the guy Rickles arguably patterned his act on, Jack E. Leonard). Of course, comics who insulted the wrong patrons ended up with scars, or broken bones, with which to remember their chutzpah. Once Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver went after organized crime in his televised hearings, the kingpins created that oasis of vice in the desert, Las Vegas.

Meanwhile, in living rooms, comedy became available to the mass public on television, in the form of sitcoms and variety shows. The 1950s saw the creation of late-night programming, a boon to comedians, masterminded by NBC executive Pat Weaver (Sigourney’s father).

Although the best stand-ups had distinct personas, they thrived on jokes and thus needed to employ writers to insure a steady stream. During the ’50s a new scene grew and with it a new ethic began to gain momentum. The spread of coffeehouses and lower-key clubs encouraged more individualistic and iconoclastic humor. Nesteroff names a trio of game-changers here: Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, and Jonathan Winters. These guys had an agility that those dependent on joke writers didn’t have. Bruce is remembered for his taboo-breaking frankness and language when satirizing social mores, Sahl for his political barbs. Nesteroff calls Winters “the comedian as a free-form artist.”

Woven throughout The Comedians are check-ins on the rise to prominence of African-American comedy. As difficult a time as black musicians had in mid-20th-century America, those who talked to an audience had it worse. Patrons of the segregated Chitlin’ Circuit (the name a take-off on the Catskills’ Borscht Belt) enjoyed talents such as Jackie “Moms” Mabley and Pigmeat Markham, who wouldn’t be accepted by the white establishment until their elder years. Redd Foxx, so raucously funny he could not be denied, was the game-changer here, easing the way for Bill Cosby, Richard Pryor, and Eddie Murphy. Political satirist Dick Gregory went further than the stand-up stage, becoming a well-known activist.

Andy Kaufman — mostly missing in “The Comedians.”

The later decades of the century bore the influence of their respective drugs of choice. During the ‘60s, pot and psychedelics fueled the skewed outlooks of the many improv groups that sprouted up, and helped motivate George Carlin to ditch the tie, grow his hair, and make his material matter. In the ’70s, Albert Brooks and Steve Martin broke ground by incorporating irony into their comedy and questioning the nature of, and need for, a punchline (David Letterman shared this sensibility). Then came the Comedy Club Boom of the ’80s, as edgy (Sam Kinison!) and ephemeral as its drug of choice, cocaine (with which some club-owners paid the acts, according to Dana Gould). The Comedians’ chapters on the ’90s (clubs shut down, Comedy Central was created, Ben Stiller and Conan O’Brien helped spawn the alternative scene) and the New Millennium (the recovery of humor after 9/11, the Internet, Twitter) are short, but give a good glimpse of comedy both mainstream and offbeat.

Within this framework, Nesteroff pauses now and then to spotlight events, such as the ascendance of Harry Einstein (father of Albert Brooks and Bob Einstein), who adopted a Greek comic persona, Parkyakarkus, and who dropped dead immediately after “killing” at a Friars’ Club roast. He pursues accusations that certain beloved figures started out as joke thieves, and presents further instances of bad behavior.

Readers of the nerd persuasion will rail at omissions in Nesteroff’s tome. I feel my beef is justified—hey, where’s ANDY KAUFMAN? He’s mentioned in passing but doesn’t even make the index. To me, he was a ’70s game-changer, up there with Brooks and Martin. Maybe Nesteroff considers him a performance artist, or thinks there’s been enough written about him. Another ’70s milestone, to me, was Martin Mull’s talk show parody Fernwood 2 Night (there’s a profile of co-star Fred Willard, but F2N isn’t mentioned). And Ernie Kovaks is given short shrift as well.

With that off my chest, I have to emphasize that I loved this book, and it will hold a cherished place on my comedy book-shelf, which includes multiple volumes on Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, um, Andy Kaufman, a history of the Borscht Belt and the indispensible Why the French Love Jerry Lewis.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.