Book Review: Grim Light Reading — Alain Robbe-Grillet’s “A Sentimental Novel”

A Sentimental Novel, which seems to be at once pornography and a parody of pornography, is designed to provoke both revulsion and titillation.

A Sentimental Novel, by Alain Robbe-Grillet, translated from the French by D. E. Brooke, Dalkey Archive, 142 pp., $13.95.

By John Taylor

When faced with the inspiring or morally uplifting stance of a literary work, French critics draw André Gide’s remark out of their hats: “It is with good feelings that one produces bad literature.” When Gide notes this in his Journal on 2 September 1940, he underscores the danger inherent in noble sentiment when it comes to writing. As he explains in the same passage, “good intentions often make for the worst art and (. . .) the artist runs the risk of damaging his art by wanting it to be edifying.” Gide mentions a famous poem that he personally finds mediocre—Charles Péguy’s Eve—and posits that the many readers admiring it “remove themselves from the realm of art and place themselves in a completely different vantage point.”

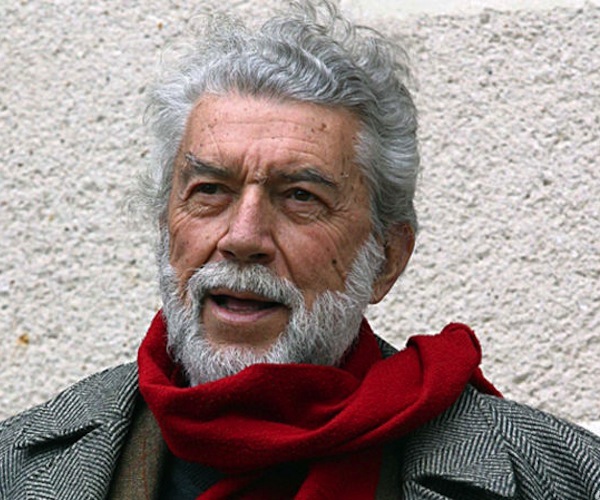

Alain Robbe-Grillet’s novel Un roman sentimental (2007), published the year before his death at the age of eighty-six and inspired, according to the author, by lifelong phantasms of pedophilia, incest, slavery, torture, and sadism in regard to young girls, tempts one to invert the terms of Gide’s apothegm. Do “bad feelings” constitute a sufficient condition for producing “good literature”? Can an artist “damage” his art by above all wanting to provoke a scandal? Of course he can, but the literary issues involved here are more complicated. This being said, A Sentimental Novel drives the reader into a corner, as it were, with respect to reading it objectively. It’s no small challenge to appraise such a work on its own terms and not to refer to extra-literary categories. The gruesomeness of the subject matter is overwhelming.

Actually, it would be more appropriate to note the few “feelings” in A Sentimental Novel, at least of the kind that can be merely qualified as “good” or “bad.” The author of The Voyeur (1955) offers breezy, detached descriptions of the cruelest acts. Action dominates the narrative, which is organized into a sequence of events (and events within events), each vying in refined awfulness with the next. When sentiments are evoked, they are bemusedly sadistic in nature. The tone is 18th-century-like and recalls the Marquis de Sade’s notoriously chilling yet also simultaneously exultant style as the narrator delights in the tortures that he inflicts or observes. Does the style redeem the contents? The translator, D. E. Brooke, catches its haughty precision in English:

Next, they would crucify her upside down, her young body, so far fairly unscathed, drawn between two vertical poles about a meter apart, to which she was attached with enormous wrought-iron nails hammered deep into her ankles, and below, through her palms. It was possible then, leisurely, to exorcise her sex thoroughly, with the appropriate tools: double-bladed hunting knives, phalluses trimmed with spikes, sharp, long-toothed saws, red hot pincers, etc. After consecutive sessions of this expiatory ritual, she was left to die a natural death, her spasms revived occasionally to affirm their breadth and intensity, with the legendary flaming tar pitch poured on her pubis and around it, which completed, by its glow in the falling night, the profoundly religious character of the ceremony.

Consisting of 239 numbered paragraphs, “the novel purports to transform into a work of literary fiction,” as the translator states in his thoughtfully argued introduction, “the author’s own avowed catalog of perverse fantasies, which he claimed had remained unchanged since the age of twelve, and that he had been making notes of over the years, every one consisting of transgressions perpetrated against young girls.”

In this regard, A Sentimental Novel prolongs the “autobiographical” turn in Robbe-Grillet’s work, which begins with Le Miroir qui revient (Ghosts in the Mirror, 1985) and continues through Angélique ou l’enchantement (Angélique or the Enchantment, 1988), and Les Derniers Jours de Corinthe (The Last Days of Corinthe, 1994).

When Ghosts in the Mirror was published, critics were surprised and puzzled that this novelist who had so provocatively emphasized fictionality and impersonality was writing his memoirs. Yet with characteristically playful provocation, Robbe-Grillet used the overarching title Romanesques for the triology, all the while admitting that, in his earlier novels as well, he had “never spoken of anything but [himself].” Moreover, he summarized the Romanesques trio back then in a way that casts light on this new book. He notably called his project

an autobiography [. . .] conscious of its inherent incapacity to constitute itself as one, conscious of the fictions that necessarily traverse it, of the shortcomings and aporias that undermine it, of the reflexive passages that break up the anecdotal movement, and perhaps, in a word, conscious of its unconsciousness.

The main character of A Sentimental Novel—an equally ironic title—is Gigi (also called Angina and Ann-Djinna). She is a fourteen-year-old girl who is being “educated” by her father. This girl, writes Robbe-Grillet, spends “the night, often entirely naked, in her mommy and daddy’s bed, in fact, the bed of her father, teacher, and absolute master and unflagging pedagogue.” Here are some perceptions of this educational relationship:

Gigi, whose education is old-fashioned, founded on absolute submission to a master (a boss, lover or husband), the respect of parents, daily domestic duties, and systematic corporal punishment, even in the absence of identifiable wrongdoing, deems it perfectly normal to be the servant of a man who has personally seen to her literary, scientific, and moral education. . . She is perched this morning on a rustic wood and straw chair at a rectangular table, where she has set her schoolbook on the traditional Jouy waxed tablecloth adorned with mythological motifs. Enveloped in a sort of very loose, pale blue djellaba, casually unfastened at the neck, that bares a satin shoulder, she is revising an oceanography lesson while her father prepares red pepper scrambled eggs.

Several other girls become involved in the tale, which is of the story-within-a-story-within-a-story genre. They will be enslaved and tortured each in turn. No details are spared, even in this relatively moderate passage:

Domenica, Domi for short, then drags her prisoner along on a leash, forcing her to advance on her knees, which she is not allowed to bring any closer to one another. If she fails to move quickly enough, or looks like she might be bringing her thighs any closer together, one of the little girls assisting with punishments (young than their leader, even) jabs her bottom with a porker’s needle, ever delighted to add to the sufferings of a disgraced rival being led to her death.

And so on and so forth until the end of the novel.

In his introduction, Brooke reveals that the project of translating the original French novel was rejected by numerous American publishers “due to its subject matter, which was considered beyond the pale.” “This pious exhibition of moral opprobrium,” he remarks, “can be classified as wrongheaded, springing from a comfort zone of profound and habitual moral hypocrisy.”

In a few articles that I have read about Robbe-Grillet’s book, it is somewhat analogously suggested that A Sentimental Novel forces the reader to face up to his own moral hypocrisy. Yet isn’t this critical touchstone akin to Gide’s negative notion of removing oneself from the realm of art and placing oneself “in a completely different vantage point”? To be sure, A Sentimental Novel, which seems to be at once pornography and a parody of pornography, is designed to provoke both revulsion and titillation. If the reader experiences these feelings, he can ask himself why this is so (and why he is like that).

Brooke’s advocacy relies on a few thought-provoking critical insights, which relate to the foregoing: how do or should we react to this book and its “material”? That is, how should we analyze A Sentimental Novel if we refuse to raise the moral (or ethical) questions about pedophilia, slavery, sadism, and the like, and attempt to read the novel on its own, strictly speaking, a-moral terms?

One of Brooke’s observations is that Robbe-Grillet creates a Brechtian “distantiation” effect by combining the form of the traditional libertine novel with the stylistic techniques that the author developed in his own version of the so-called New Novel. The translator ascribes a “feeling of unreality” to one’s reading of the novel, adding:

The close-up descriptions of the machinery of torture—the pulleys and winches and their operation, the materiality of the gruesome dildos, seats of nails, the multiple suspended parallel blades that penetrate flesh, the virgins strung up in a circle by their feet, or the redheads fed to rapid dogs—all in polished, almost scientific language, with no hint of a moral dimension, produce an unholy kind of terror and pity and firmly relegate these scenes to the realm of the unreal from which they came.

We can sense this “unreality” as we read if, once again, we decline to raise the corresponding moral (or ethical) issues and, furthermore, to assimilate the fictional events related in the novel to the type of scabrous real events of which we hear daily through the media. It must be said that the fictional horror of A Sentimental Novel is not all that far removed, in both spirit and practice, and including its ritualistic and theatrical aspects, from events that take place in our world. “Distantiation” notwithstanding, it is difficult not to think of them. This can increase the reader’s discomfort or, possibly, secret fascination. Ever a provocateur, Robbe-Grillet surely planned it this way from the onset. Ultimately, there are no redeeming factors. It occurs to me that this is the point that Robbe-Grillet would like to make about human existence.

In the first three pages, he establishes the indeterminacy of the setting, the time, and the characters—notably himself. Such an opening recalls how his novels from the 1950s and 1960s function. A sort of arch-literary framework is created early on, and this also generates the distantiation. It is refreshing to be reminded, as if we had forgotten, that the rudiments of storytelling can be called into question so smoothly. “At first sight,” begins the narrative,

the place in which I find myself is neutral, white, so to speak; not dazzling white, rather of a non-descript hue, deceptive, ephemeral, altogether absent. (. . .) I don’t know what I’m doing here, nor why I’ve come, with what conscious or impulsive intention, that is, if one can even speak of there having been an intention at some point. . .

The sadism slowly but surely begins on page four. As Gigi reads aloud, her “master” father is “as attentive to the prosody as he is to posture, [appraising] his lovely schoolgirl without the slightest indulgence, prepared to punish with a single, dry snap of his baton the smallest mistake in reading, rhythm, or even diction.”

The novel does little more thereafter than chronicle punishment. Brooke rightly mentions that “lighter touches do abound” and isolates some passages where Robbe-Grillet “is clearly having fun.” But once one grasps the central idea—the sadist fantasizing that relentlessly (and rather boringly) links one event or vision to the next—is there really any literary need to read further, unless, of course, one “likes” this kind of imagery? Secondly, do the author’s stylistic skills, here especially visible in his cynical and clinical descriptions of cruelty—suffice for placing this book in Gide’s “good literature” category?

The skills suffice in this respect. But one fundamental literary drawback persists. Robbe-Grillet is fascinated by extreme sadomasochistic sensations, which imply little or no ambiguity of sentiment. Although the narrative structure shows some intriguing indeterminacy, the sentiments evoked are determinate, not indeterminate. Such extreme, determinate sentiments certainly resemble in no way the “good” feelings that Gide impugned, but they nevertheless remain simplistic one-dimensional ones. I see such emotions as lines, at best as forms (as if they were ideas, which I think they actually are), but not as vague, shifting, three-dimensional shapes or volumes that can be peered into and pondered. And it is with such unambiguous linear feelings that Robbe-Grillet produces, well, obviously not “bad literature,” but a grim book paradoxically offering too much “light reading.”

John Taylor is the author of the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction, 2004, 2007, 2011) and Into the Heart of European Poetry (Transaction, 2008). His recent translations of French poetry include works by Philippe Jaccottet, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Louis Calaferte, and José-Flore Tappy. His most recent personal book is If Night Is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press).

Tagged: A Sentimental Novel, Alain Robbe-Grille, french fiction, pornography

I put this book next to jealousy and in the labyrinth and then I made sense of it all. My mistake was to separate it from the rest of his oeuvre. The rows of banana trees, the snow falling around the soldier, the numbered sets of assaults are all equal. The setting is so detailed that it engulfs the entire narrative and as such disappears or becomes meaningless. To make sexual torture and swirling snow equal in depth is really good reading in my skull. Also the structure and subject matter is the same as 120 days of Sodom, although not nearly as grim. It’s not a nod, it’s identical.